By Michel Beaudry

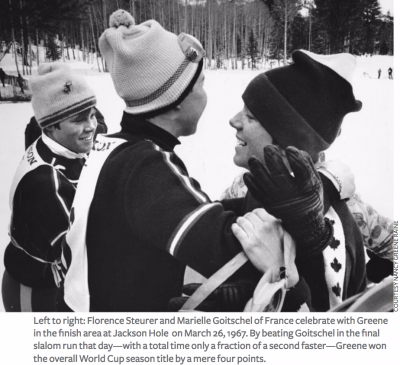

Nancy Greene of Canada came from behind to win the 1967 inaugural World Cup overall title by the slimmest of margins in a thrilling final race.

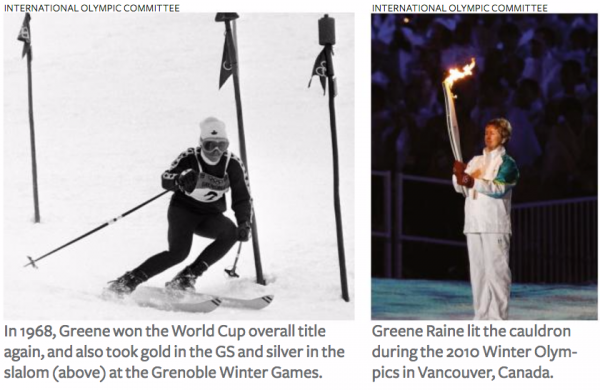

Nancy Greene Raine is a force of nature. A two-time overall FIS World Cup champion (1967-1968) and an Olympic gold and silver medalist at the 1968 Winter Games, Greene Raine was raised in the ski-mad town of Rossland, British Columbia. Her contributions to the sport are legion. Along with husband Al Raine, she was an early promoter of Whistler and Blackcomb Mountains in BC before being drawn east to Sun Peaks in the mid-1990s, where the couple has played an integral role in making it one of the country’s most successful year-round mountain resorts. Her namesake program—the Nancy Greene Ski League—has been the gateway to racing for young Canadians for nearly 50 years. In January 2009, she was appointed as a Conservative member of Canada’s Senate.

In this exclusive interview, conducted in November 2016, Greene Raine, 73, looks back at the 1967 World Cup season, which she won by the slimmest of margins after mounting a late-season comeback.

Only one race left. And the young ski racer they call Tiger knows exactly how high the stakes are. Considered by many to be out of the running for the inaugural World Cup after failing to score any points for nearly two months, 23-year-old Nancy Greene of Canada has mounted an impressive comeback these last few weeks. It started with a third in Franconia, followed by a big-time win in Vail; then came Jackson Hole and a crushing victory in yesterday’s giant slalom. Suddenly her main rival is within reach again. But France’s Marielle Goitschel is still the overwhelming favorite. The only way Tiger can be crowned 1967 overall champion is by winning the slalom today. It’s all or nothing.

Still, Greene is coming into Sunday’s race with a big head of steam. “By this point in the season,” she explains, “I know that if I ski well I can beat anyone. So I’m going for victories, not for fourth-place finishes.” Her giant slalom result on Rendezvous Mountain the day before underscored that attitude: She dominated the one-run race by 1.72 seconds. She’s now only one win away from the title. She knows she can do this.

But the two-run slalom offers its own challenges. “The first run is always a bit of a gamble,” she says. “You want to go flat out and take risks, but you also want to make it to the second run.” Clearly, the same thing is running through the minds of her opponents. For when Sunday’s first run is completed and the times tallied, barely a tenth of a second separates Greene from Goitschel and French teammate Florence Steurer. The ski gods obviously want a dramatic finish to the season.

Who is this Canadian woman who dares to challenge the French skiing juggernaut of the late 1960s? And how the heck has she managed to hoist herself atop the World Cup standings?

Disappointment in portillo

Although Nancy Greene’s story really begins in the remote mountain town of Rossland, British Columbia, one need only revisit the 1966 World Alpine Skiing Championships in Portillo, Chile to get a glimpse of her exceptional drive to succeed.

“I went down to South America with very big goals,” she begins. “I fully expected to be on the podium there.” Makes sense. As a sixteen-year old newcomer to the Canadian Team, Greene had witnessed her mentor and roommate, Anne Heggtveit, win gold at the 1960 Olympics in Squaw Valley. And it had inspired the teenager tremendously. Now, six years later, the experienced racer thought she too could bring skiing glory to her country. But could she really do it? “I was too nervous in the slalom and didn’t perform very well,” she says. “But the downhill was coming up and I knew I was skiing fast.”

Alas, the downhill proved even more disastrous. “I remember my coach quietly telling me in the start gate: ‘Win it! Win it for me, Nancy.’” She sighs. “I guess that got me a little too excited. Near the bottom of the course there was this big roll over a road tunnel. In training, I’d always wind-checked before hitting it. But on race day I decided to take it straight.” Bad decision. “I crashed and somersaulted right into a retaining wall made of ice. I knew I had a good run going. I could even see the finish line…So frustrating.”

Her best event, the giant slalom, was next. But badly bruised from her downhill fall (and skiing with an undiagnosed fractured tailbone), Greene finished just out of the medals in fourth place.

Meanwhile, the French team, Les Bleus, had dominated the championships: Two out of every three medals had gone to them. As for Marielle Goitschel, she had won everything but the slalom…and only teammate Annie Famose had skied faster in that race.

But Tiger didn’t come away from Chile entirely empty-handed. Says Greene Raine: “Rossignol had just come out with a new fiberglass ski they wanted me to try, called the Strato. So I tested a pair in La Parva before the World Championships. And I loved skiing on them. But I decided that I shouldn’t switch skis before such a big event, and I hid them under a huge stack of ski bags so I wouldn’t be tempted.”

Nancy returned home with her new skis and an even greater determination to win. “My coach, a former racer called Verne Anderson, also lived in Rossland,” she says. “And together we trained with a veteran who’d been a fitness trainer in the military. He knew nothing about skiing. But he knew everything about weight training.”

Greene had another secret weapon. The Canadian Team was now based out of Notre Dame University in nearby Nelson, BC. “It was so practical to have a place where everyone could live and work and study together,” she says. Smiles. “Besides, training with the men’s squad meant there was always somebody to chase.”

Things were also progressing well on-snow. And the more she skied on her new Rossignol skis, the more Nancy realized how much they suited her style. “They were 207cm giant slalom skis, and they really set me up for the season. In those days the thinking was that fiberglass skis were great on hard snow but you needed metal skis to go fast on softer snow.” She stops. Laughs. “Well, I trusted those Stratos so much that when I left for the first European races of the 1967 season, I left my metal skis at home.”

Things were also progressing well on-snow. And the more she skied on her new Rossignol skis, the more Nancy realized how much they suited her style. “They were 207cm giant slalom skis, and they really set me up for the season. In those days the thinking was that fiberglass skis were great on hard snow but you needed metal skis to go fast on softer snow.” She stops. Laughs. “Well, I trusted those Stratos so much that when I left for the first European races of the 1967 season, I left my metal skis at home.”

It was a radical decision—and a risky one, given the dramatically different way ski races were being organized that year. “We really didn’t know much about this new circuit called ‘The FIS World Cup’ when we got to Europe in January,” she says. “I’m not even sure the Canadian Ski Association fully understood what was going on. We were all a bit surprised by the changes.”

And yet from the moment she came charging out of the gate that year, Tiger made her presence felt. Two World Cup races in Oberstaufen, Germany (a slalom and a giant slalom) and a gap of 1.24 seconds between her and the next finisher in the GS. At the second World Cup stop, in fabled Grindelwald, Switzerland, Greene won twice more, this time adding downhill points to her mounting World Cup lead. Five races, four victories. The Europeans were in shock.

Greene continued to ski well, if not quite at the same scintillating pace. In Schruns, Austria she was third in the slalom and fourth in downhill. Though they were closing the gap, the French women were still behind in the race for the overall crown.

But the members of the Canadian Team had race obligations back in North America and were scheduled to return home. Would Greene be forced to accompany them? “It wasn’t common practice to leave athletes behind to compete on their own in those days,” explains Greene Raine. “But at the last minute, our coaches decided that my teammate Karen Dokka and I would remain in Europe for one more event.”

They didn’t have it particularly easy. “We were responsible for everything,” she says. “We even had to prep and wax our own skis. Still, it was a lot of fun. It felt very liberating to be left alone like that.” But the lack of team support began to show and she failed to earn any points at the next two races in St-Gervais, France. Still, when she left for home in February, many on the circuit were convinced Tiger was making the biggest mistake of her career. By missing the last European stops, they argued, she was leaving the door wide open for her rivals to score points.

The World Cup points formula was complex that year: only the top three results in each discipline would count toward an athlete’s total in the race for the overall title. “But my dad, the engineer, had crunched all the numbers,” she says. “He was confident that there were still enough races in the spring for me to make up the point deficit.”

And so was Nancy. “I knew that I had to start strong in those first March races in New Hampshire. And if I could do that, well…” Although it was less than the victory she needed, Tiger managed to scratch her way onto the giant slalom podium in Franconia. But it was during the slalom the next day that she had her big revelation.

“The Canadian Team had been working with plastic boots since the previous spring,” she remembers. “One of our coaches, Dave Jacobs, had struck a close relationship with Bob Lange and so the Canadian men had been testing his boots for some time. Well, my feet were so small that it took Lange a long while to make a boot my size. But by March of ’67 they were done, and I received my first pair just before the slalom in Franconia.” A pause. “I remember skiing with them that afternoon. I couldn’t feel a thing. ‘I can’t ski with those,’ I thought. ‘Way too stiff.’”

But the skies cleared that night and Nancy watched the day’s mushy March snow freeze into a hard, firm surface. “I was still struggling with my decision: go with my soft leather boots or try the stiff plastic ones. But then I realized: ‘It’s going to be boilerplate tomorrow. What better time to use the new boots?’”

It wasn’t love at first try. “I was all over the place on my first run… skiing really raggedy. But I got the hang of those boots by the second run and skied really well. Unfortunately I didn’t finish—I caught a tip near the bottom of the course. Still, I knew what I could achieve in those boots with a little practice.”

She never looked back. By the giant slalom in Vail, Greene was in full form again, winning the run by more than half a second. Only the World Cup finals remained. “My dad was still tabulating the points,” says Greene Raine. “’All you have to do,’ he said, ‘is win the last two races and the title is yours.’”

Last Stop, Jackson Hole

For some athletes the pressure would be unbearable. But Tiger thrives on it. Like a laser-guided missile, Greene launched into her Grand Teton weekend by blowing her competitors away in the season’s penultimate race. By the next day and the start of the slalom’s second run, Greene was in a three-way tie for the race lead. The overall title was now within her grasp. But the Canadian had to win the run.

“The course-setter for the second run has provided the racers with a choice,” she remembers. “There’s an elbow set halfway down the course. The rhythm goes one way, but if you jam your skis hard, you can straight-line the gates, and come out of the elbow with way more speed. But it’s risky…”

Greene sees the trick passage during inspection and thinks, ‘I’ve got nothing to lose. I’m going to shoot the gate.’ But it might prove costly. While most of the women take the easier route, the racer just ahead of her attempts the straighter line, catches a tip at the top of the elbow and takes out all the gates.

Now it’s the Canadian racer’s turn to worry. “There I am standing in the start gate thinking to myself: ‘If they re-set the course any different than it was, I’m hooped.’”

Meanwhile, the announcer at the finish line is whipping up the crowd. What he doesn’t know is that there are loudspeakers at the start too. Says Greene Raine: “I’m still in the start gate, waiting for the course to be cleared, and all I can hear is the emcee saying over and over: ‘The next racer is Nancy Greene. She needs to win here, folks, second place isn’t any good.’” She laughs. “I think it’s around the fourth time that he says ‘this could be the most important moment in her life’ that something snaps inside me. ‘This is ridiculous,’ I think. ‘It’s Easter Sunday. Look at the view. What a beautiful place this is.’” She pauses for a beat.

“I’ll always remember that moment,” she says. “It was like an out-of-body experience. And it put me in just the right frame of mind to race that final run.” Another stop. More laughter. “Well, I shot the gate just like I’d planned, and made it safely to the finish line. I think I beat Marielle by 0.07 of a second in the total time.” But it was enough. Tiger had just won history’s first ever World Cup of skiing by the merest of margins: four points (176-172). It was a racing tour de force rarely matched since. And it ensured Nancy Greene’s place in the ski pantheon of all-time greats.