I know the small box it’s in, but right now, I couldn’t tell you which large box the small box is in.” Deb Armstrong is talking about her gold medal from the 1984 Winter Olympics in Sarajevo. “I could find it if someone wanted to see it,” she assures me. “It’s a ‘working’ medal.”

The same could be said of its owner, who today, at 52, continues her quest to develop as a skier. In fact, she admits to being a little sensitive about being known

as “Deb Armstrong, Olympic gold medalist.” “I didn’t ‘retire’ from skiing,” she explains. “I continue the pursuit of lifelong learning through the sport I love.”

That pursuit has included a stint on the PSIA Demo Team and six years as alpine director for the Steamboat Springs Winter Sports Club, where this fall she saw the fruition of a four-year project she championed, the $2.5 million Stevens Family Alpine Venue. Located at the Steamboat Ski Resort, it’s a dedicated training and competition site for alpine, telemark and snowboard racers.

In her current position, leading the U-10 program for SSWSC, Armstrong finds her evolution as a skier more relevant than ever. “If you’re going to teach kids, they don’t care about a gold medal after five minutes. It’s fun. But it’s not enough.”

The Storybook Career

Hugh and Dollie Armstrong raised their kids, Debbie and Olin, to love learning, the outdoors and all manner of recreation. Weekends were spent skiing and hiking in the mountains near their Seattle home, where Hugh was a clinical psychologist at the University of Washington and Dollie taught school. The kids’ first turns were at Alpental. Both took to racing there on weekends, while participating in multiple sports during the week. “I was too short for basketball,” explains Deb, though it didn’t stop her from playing for inner city Garfield High School. In skiing, however, her athleticism made her an exceptionally quick study. Even after missing two entire ski seasons at age 12–13, when the family moved to Malaysia, Deb shot up the junior ranks, winning her Junior Olympic competition by two seconds, and gaining the U.S. Ski Team’s attention.

Her international ascent was similarly steep. “She was very fast, if she made it,” recalls Michel Rudigoz, head U.S. women’s coach at the time. “She could let ’em go!” Armstrong won her very first World Cup downhill training run, and within two years was in the World Cup downhill first seed.

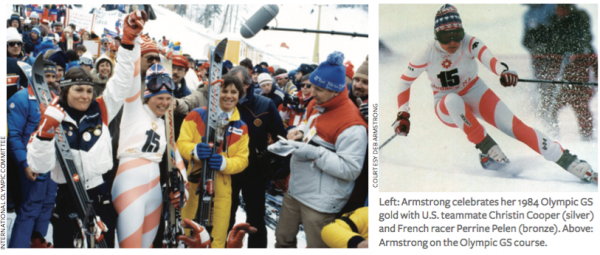

Going into the 1984 Olympics, having just scored her first podium five weeks earlier (a super G bronze in Puy Saint Vincent, France), Armstrong’s star was on the rise. But she was hardly conspicuous amidst a dazzling roster of World Cup champs like Tamara McKinney, Christin Cooper, Cindy Nelson, Phil and Steve Mahre, and brash downhill sensation Bill Johnson (see page 33). Knowing Armstrong’s competitive nature, Rudigoz offered to make her a bet. Before he could make his wager for the DH race, she beat him to the punch: “Bet you $50 I medal in either event.” Determined to fully experience Olympic competition by staying in the moment and having fun, she nabbed gold in the GS, ahead of favorites Cooper and McKinney. Four years later, after six years on the World Cup and 18 top-ten finishes, Armstrong retired from the U.S. Ski Team, at age 24.

After her World Cup career, Armstrong hungrily immersed herself in academics—“I wanted to read books, write papers and fill in the gaps of what I’d missed while skiing”—and earned a history degree from the University of New Mexico. When the inevitable question of “What now?” surfaced, she listed priorities: The next chapter had to meet her intellectual need to teach, her physical need to be athletic, and her spiritual need to be in the mountains. “Those three things brought me right back to skiing,” says Armstrong.

In 1995 she became a skiing ambassador at Taos, and often felt ill-equipped to answer the most technical ski questions from guests. To address that, she set about earning her PSIA level 1, 2 and 3 certifications, eventually landing a spot on the PSIA Demo Team.

The Plot Twist

In the fall of 2004, Armstrong got bitten by a tick carrying the Borellia virus. “One weekend I rode my bike 200 miles and by Tuesday I was on life support,” she says. Suffering from Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) and sepsis, she spent six days on a ventilator in a medically induced coma. Sidelined for the 2004–2005 ski season, she eventually recovered—but unusual symptoms lingered. “I smelled the drugs coming out of me for a year,” recalls Armstrong, who later wondered if she was “the same Deb.” (Studies show that one-third of people who survive an ICU experience suffer from PTSD.)

In 2007, daughter Addy was born. Armstrong and her partner moved to Steamboat, where Deb took a position as Technical Director of the Ski and Snowboard School. Soon she was lured back into the racing world as Alpine Director of SSWSC. The job—working directly with athletes, parents and staff; managing schedules and programs; fundraising and working with the city and the ski area—was demanding.

She started noticing behavioral changes, like agitation and irritability, confusion, trouble concentrating, and difficulty being with friends. At the same time, she also went through a separation. “Personally, I was barely making it,” she says. “I kept thinking that day-to-day life should not take this much energy.” A concussion in the fall of 2013 was the final straw. Even after the acute symptoms passed, she had to go home to rest at noon each day. That spring, after six years of running SSWSC, Armstrong stepped down. She restructured her job and her life, reducing stress where she could, but still not understanding her symptoms.

The New Reality

Last spring, she finally connected with neurologists at Stanford University for an exam and MRI and then with Dr. Pamela Kinder at Blue Sky Neurology in Aurora, Colorado. Kinder suspected that Deb, like many athletes, was underreporting the head trauma she had suffered over the years. “Today we know that there can be significant and damaging injury with no loss of consciousness,” says Kinder. Deb recalled a head injury in 1980 at age 14, and another in 1995, but surely there were other crashes along the way, and more soccer-ball headers than she could possibly count.

A SPECT scan revealed that Armstrong was suffering from the cumulative and long-term effects of Traumatic Brain Injury (TBI), something much talked about in the NFL, but less acknowledged among ski athletes. Kinder credits Armstrong’s “Olympian brain”—especially adept at overcoming physical and emotional challenge—for the ability to maintain her previous immense work responsibilities while quietly coping with debilitating symptoms.

For Armstrong the diagnosis was both liberating and validating. Managing her condition, which involves deficits in her short term and working memory, is something she had instinctively done by restructuring her life “and writing everything down.” Now, however, she can do it with more acceptance and understanding.

Today the woman who dedicated her 40th year to “throwing helis” is in her element, pushing her skiing skills and working not only with the 80 young kids in her program but with their coaches and parents. She regularly makes and posts instructional videos, and leads clinics and conversations that foster technical development and a healthy culture and learning environment for the kids. She gets to work with Addy, who recently turned nine, and to spend her time figuring out how to best utilize Steamboat’s facilities to create a unique experience for eight- and nine-year-olds.

“Personally and professionally the job could not be a better fit,” she says. “I’m out all day, reaching people, teaching, guiding, helping. When not coaching, I am a 100 percent hermit in my house, feeding my introvert self.”

Armstrong came away with an abiding sense of gratitude for being able to live without the stress of always rising to the occasion. “I can handle doing that some of the time,” she assures, “but not for everyday life.”