Radical racing invention, or a variation of a long-established technique? By John Fry

Was the Egg (oeuf in French, Ei in German) a radical ski racing invention? Or merely a stage in the steady progress made in streamlining the skier’s body to achieve faster speeds?

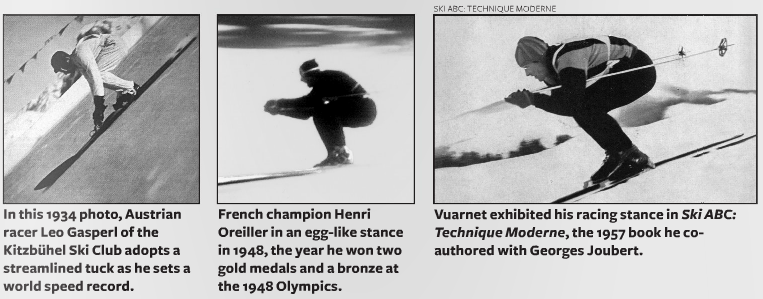

In France the question is alive, and afire with controversy. Jean Vuarnet, his son Alain, and his supporters tell of the enormous research he did to achieve his invention. They cite the French newspaper Le Figaro, which once compared the Egg to the Fosbury Flop, a single change in body action that eventually enabled all high jumpers to leap higher. Vuarnet also suggests retaliation—that doubts about his “invention” only began after his involvement in the controversial firing of six racers from the French ski team in 1973. Critics and opponents, like Jean-Claude Killy, say the Egg wasn’t an invention, but merely a variation of what downhill Olympic gold medalists Henri Oreiller and Zeno Colò were already doing a few years earlier.

Experts in the rest of the world appear baffled by why there should be a controversy. They mostly see Vuarnet’s work as part of speed skiing’s changing aerodynamics, going back at least to 1930 and 1931, when Gustav Lantschner and Leo Gasperl set world speed records, and earlier to the 19th century, when California gold miners sat low over their long skis to speed downhill. It’s hard to find anyone outside of Gaul who thinks l’Oeuf is anything but a stage in the evolution of the hocke, crouch, tuck and streamlining of the racer’s body. Vuarnet first exhibited his stance in Ski ABC—Technique Moderne. The 1957 book contains a picture of him in what is clearly the optimal aerodynamic stance of the time—poles and lower arms parallel to the skis, which, however, are not as far apart as in later editions of Joubert’s and Vuarnet’s books. No textual analysis is offered.

The foreword to Ski ABC was written by Ralph Miller, who helped with the first English-language edition, and who set a world speed record at Portillo in 1955. Miller thinks Vuarnet’s stance was simply a further refinement of body positions designed to reduce air friction.

The 1960 edition of Ski Moderne (Arthaud) contains excellent photos, illustrations and text about l’Oeuf. It’s the first detailed description I can find in print. A photo sequence of Vuarnet from the pages of Sports Illustrated is wonderful. That magazine, and others at the time, credited Vuarnet’s Squaw Valley downhill gold medal to his use of metal skis, as well as to his superior aerodynamic stance. The Austrians were the big losers. “We missed the wax,” Anderl Molterer told me recently.

I have a copy of the German Ski Moderne, a translation by Hanspeter Lanig, published in 1963. Via e-mail, Lanig told me that l’Oeuf was an invention (erfindung) of a word, not of a technique. And Dick Dorworth, the American who set a new world speed record at Portillo in 1963, says he knew about Vuarnet’s Egg. He thinks stance is shaped considerably by the racer’s own morphology. In competitive downhill racing, the V-J or Oeuf is a technique mostly limited to shaving seconds on flatter sections of the course. How valuable it is depends on the terrain—the Streif on Hahnenkamm and Birds of Prey at Beaver Creek yield less advantage for l’Oeuf than, say, the Sarajevo Olympic downhill of 1984, or the Squaw Valley downhill of 1960.

Austria’s Stefan Kruckenhauser was said to have invented “wedeln” about the same time as Vuarnet “invented” the egg. Both drew their inspiration from racing technique. Lanig might say that the word, not the act, is the invention.

My own view is that Vuarnet’s writing and photos brought into public view the final ideal stance for attaining the highest speeds on flatter sections of downhill courses and in setting speed records—an evolution that had begun at least 30 years before. Joubert and Vuarnet’s 1966 Comment se Perfectionner à Ski (How to Ski the New French Way) shows a further evolution: the bullet or bolide. It was a super-egg-like streamlining of the body, with legs even more splayed, torso even more compressed between the legs. Here, arguably, was the final form. It hasn’t changed much in the ensuing 50 years.