A force of nature on the racecourse, Hermann Maier now enjoys a slower way of life.

By Patrick Lang

Austrian Hermann Maier is such an outsize presence in our memory that it’s hard to wrap one’s mind around the fact that he retired from racing 13 years ago. Now, turning 50 on December 7, he seems to have settled into a life of contemplative, pastoral domesticity.

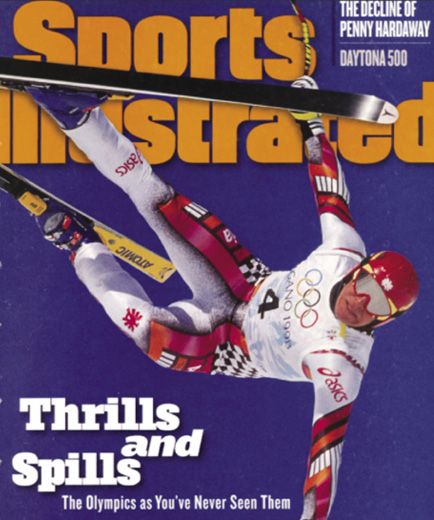

(Photo top: Maier on the Hahnenkamm. During 11 seasons he won 54 World Cup races, four overall World Cup titles 10 discipline titles, plus 10 Olympic and World Championship medals, including five golds. Photo courtesy Hahnenkamm.com)

The nickname “the Herminator” was a natural fit for him as a competitor. Off the course he could be a smiling, friendly giant, but when he wore his ferocious race face, he became a fearsome mountain troll. On skis he was a force of nature, seemingly as unstoppable as a hurricane. In fact, he was unstoppable. The most famous image of Maier was taken by the late Carl Yarbrough (see Lives, page 30) at the 1998 Nagano Olympics downhill, as he was flying off the turn seven bump, heading toward a horrific crash. But he shook off the snow and won gold three days later in super-G, then again in GS. (He told a reporter, “If I win this, I’ll be immortal.”)

Nagano Olympics, in Super-G and GS.

But first (right) . . . Wikimedia photo.

in the downhill, immortalized by

photographer Carl Yarbrough.

Then in August 2001, after winning 12 crystal globes, Maier came back after nearly losing a leg in a motorcycle accident to win two more World Cup globes plus a FIS World Championship gold. Over 11 seasons, he scored 54 World Cup wins, 96 podiums, four overall World Cup titles, 10 discipline titles and 10 Olympic and World Championship medals, including five golds.

Then at age 36, in October 2009—a year after his last World Cup victory—he abruptly retired. After two days of free skiing on the Soelden glacier he announced to the press, “It was so great to ski without pain, and I fully enjoyed it. I haven’t had that kind of feeling for a very long time. . . . I was so happy to move again so effortlessly on that slope. It made me reflect for a while, and then I decided to leave in relative health.”

He told Rainer Pariasek, an Austrian TV announcer, that he wanted “another kind of routine, without a fixed program of hard training, travel, hotel rooms and racing. I felt ready for something else and to feel free.”

The Tough Kid

Hermann Maier Sr. and his wife, Gertraud, ran a ski school in Flachau, Austria, not far from the original Atomic ski factory and worked summers as a bricklaying foreman. He put his oldest son on skis at age three. “[Hermann Jr.] wouldn’t listen to advice,” remembers his mother. “But three days later he was skiing well, mostly straight down the hill.”

When Hermann Jr. was 15, his dad fell 25 feet onto a concrete surface after a scaffold collapsed. The younger Maier barely weighed 100 pounds, but he dropped out of school at the regional ski training center to help support the family and began his apprenticeship as a mason. Over seven years he put on another 100 pounds of muscle. “My body got used to demanding exercise,” he says. “I guess without that tough job I wouldn’t have achieved the career I had.”

“He was a tough kid,” recalls his younger brother Alexander. “He was always pushing, and it wasn’t easy for us as playmates.” Maier also entered the other family business, becoming a certified ski instructor. He kept running gates and entered some local and pro races, using hand-me-down equipment, and had some promising results. But by fall 1995, when he had made up his mind to quit laying bricks and race seriously, he was already 23 and too old to qualify for the regional squad.

Maier found local connections. He got some fast skis from Atomic and, more importantly, he got great physical training advice from Heinrich Bergmüller, the long-time director of the Olympic training center at nearby Obertauern. In the gym and on the running track, Maier worked longer and harder than anyone else.

known for his indefatigable work ethic.

Players Bio photo.

Late Bloomer

That training compensated for the long gap in his racing resume. Maier startled the national team coaches with a blistering performance as a forerunner at a World Gup GS in Flachau in January 1996. That same month he powered his way to second, first and first in three Europa Cup GS events in France, followed by two super-G victories at home. He clinched the Europa Cup overall title and scored his first World Cup points that spring.

Promoted to the national squad for the 1996–97 season, Maier crashed and broke his hand in his very first World Cup downhill, at Chamonix in January 1997.The injury kept him out of the World Championships at Sestriere, Italy, but—despite wearing a cast as a protection for his injury—he came back to finish second and first in back-to-back super-G’s at the end of February on the challenging Kreuzeck course in Germany. The latter was his first World Cup victory.

Racers and coaches studied video of Maier’s runs, trying to puzzle out the secret of his speed. It turned out to be power: he was simply strong—and determined—enough—enough to hold those fast Atomic skis on a carving edge, stick to his line at higher speeds. The thousands of hours lifting bricks and pumping iron had paid off.

"You need an amazingly strong mental attitude to survive what Hermann went through during all those years,” Bergmüller later told me. “It's pretty much unbelievable." It was around this time that his teammates nicknamed Maier the Herminator.

He started the next season strong, with two podiums at Tignes, France, following by his maiden win in GS at Park City, Utah. Then, on December 5, at the second running of the Birds of Prey course at Colorado’s Beaver Creek, Maier took second in downhill, behind his teammate Andreas Schifferer, and won the super-G the following day.

After the Christmas break came an astonishing string of eight victories, including his first downhill win, on the treacherous Stelvio course at Bormio, Italy, plus four additional podiums. Going into the Nagano Olympics, Maier had won every super-G on the schedule.

His sudden rise to dominance on the Austrian ski team created some resentment among the established racers. The Austrian speed skiers in that era were accustomed to sweeping the podium and taking up to six or seven of the top 10 finishes. As the newcomer, Maier seemed to bump everyone down a step. Only Schifferer became a friend.

2013 FIS World Championships.

Worldwide Fame

At the Nagano downhill, Maier carried blistering speed into the turn seven bump (where the eventual medalists were able to check their speed) and soared onto the cover of Sports Illustrated. A weather delay gave him three days to heal his bruises, and he then won the super-G by a decisive .61 seconds and, later, the GS by .85. Maier finished the season as overall World Cup champion—the first from the Austrian men's team since Karl Schranz in 1970 —and earned globes in GS and super-G (he finished second in the downhill standings).

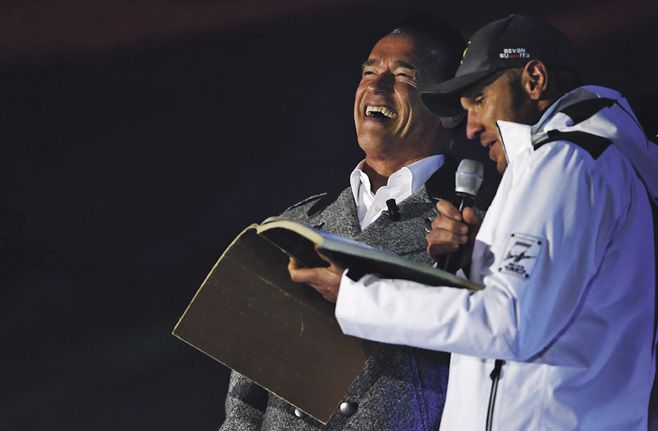

At Nagano, I worked with Tim Ryan at CBS Sports. Ryan was amused when I told him about the Herminator nickname. He reached out to one of Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Sun Valley ski instructors and relayed Maier’s contact information. Schwarzenegger responded, and the following spring Maier and his brother Alexander had a wienerschnitzel dinner at the star’s home in Los Angeles (cooked by Mama Gertraud herself), followed by a joint Terminator-Herminator appearance with Jay Leno on The Tonight Show.

In 1999 Maier won World Championship gold in downhill and super-G; in 2000 he scored a record 2,000 World Cup points and took the overall, downhill, super-G and GS crowns. He repeated the championship wins in 2001. At 29 years old, he felt invincible while training in Chile that summer, consistently finishing practice downhills at least a second ahead of his teammates.

“It was absolutely amazing,” he recalls. “I was in the form of my life and looking with great excitement for the upcoming season and the 2002 Olympics.” He expected another dominant World Cup season and downhill victory at Salt Lake City. Some members of the press speculated that he might retire after that.

A Shattered Leg

In August, Maier was riding his motorcycle home from a workout at the Olympic training center when he was sideswiped by an inattentive German driver. He never lost consciousness after crashing and knew immediately that he might lose his right leg, which was shattered below the knee. Flown to Salzburg, he was lucky enough to be treated immediately by Artur Trost, one of Austria’s top surgeons, and his team. Going into surgery, Maier begged Trost, “Please save my leg.” After seven hours of surgery, Trost did just that. In the aftermath, however, massive damage to the huge muscles of his thighs and lower back led to life-threatening sepsis, exacerbated by near-overdoses of painkillers.

Nonetheless, as soon as Maier realized that he could still move his toes, he shifted focus immediately to rehabilitation, starting with gradual upper-body exercises. “I’m convinced his perfect shape definitely helped him to survive and overcome,” says Bergmüller.

It can’t be said that Maier sat out the 2001–02 ski season. He sweated it out, working every day to regain his leg strength and endurance. By January he was able to run, ride a bike and cross-country ski. He had lost the feeling in his right foot and calf, so when he returned to using Alpine skis in March, seven months after the accident, he skied on one leg. During downhill training in Chile that July, he badly bruised his right leg at the boot-top, which set him back for a long time. At that point, a full recovery seemed in peril.

in the 2003 Tour de France

prologue.

Comeback

It’s a mystery how Maier managed to pull together a spectacular second career. He returned to the World Cup circuit in mid-January 2003 and two weeks later won a super-G in Kitzbühel, Austria, in miserable weather. His next race earned him the silver medal in super-G at the World Championships, in a tie tying with Bode Miller behind Austrian teammate Stefan Eberharter.

On July 5, Maier rode as a pacesetter (equivalent to a forerunner) in the prologue to the 100th Tour de France. It was a four-mile (6.5km) time trial, starting at the Eiffel Tower, and he didn’t seem to take it seriously, having spent most of the preceding night exploring Parisian nightlife. On the bike he looked massive, outweighing the average pro rider by 50 pounds. His time would have brought him in at 199th—in a field of 198.

Only one year later, in 2004, he was locked in a race for the World Cup championship with Eberharter, the defending champ. Maier managed to capture it at the World Cup Finals at Sestriere in March. A year later, he clinched World Championship gold in GS at Bormio, then silver in super-G and bronze in GS at the 2006 Turin Olympics.

Maier won a few more races after that, but over the next two seasons his career gradually began to wind down. When he quit at the beginning of the 2010 season, he was close to turning 37.

Two years later he was back in the news with a Herminator-strength athletic performance. Maier took part in a made-for-TV survival adventure celebrating the 100th anniversary of Roald Amundsen’s race, on skis and with dog sleds, to the South Pole. He led a four-person Austrian team that competed with a four-person German team, with competitors racing for 250 miles on skis across the Antarctic ice cap to the pole. Each racer pulled a sled loaded with supplies and camping gear. The Austrian team finished in nine days (one member had to drop out due to frostbite), beating the Germans by 46 hours.

“It surely was the toughest experience ever for me,” Maier says. “But I was ready to face it after all that I went through in my life.” Soon after, he was ready for a quieter existence.

At Peace, on Top of the World

In partnership with Austrian World Cup slalom champion Rainer Schönfelder, Maier opened the Adeo Alpin Hotels, four budget-priced sport hotels that serve skiers in the Salzburg region and the Tirol. With the makings of a subtle comedian, Maier also continues to make a popular series of humorous TV commercials for the Austrian-based Raiffeissen Bank. And he makes rare public appearances at World Cup races.

But private life is private. Maier has long guarded his young family from the press. He lives in the lakeside village of Steinbach am Attersee, about 30 miles east of Salzburg, with his wife, Carina Schneller. The couple hasn’t even revealed the names of their kids to the press. The twins (identified as Liselotte and Valentina by the Austrian press, without any proof), are now nine years old, and a third daughter is seven.

When he does ski, Maier likes solitude and a slower pace. He spends days ski-touring on pristine snowfields far above the resort towns. “I don’t exactly know how many days I am now skiing in the winter, mostly far from the crowd,” he says. “For sure, it’s not as intense as it used to be. I’m mostly seeking for pleasure on snow and looking for the best possible conditions.”

The Herminator is not a hermit, though. From time to time, he is willing to share things with a national television audience. In 2016 he hosted a show, Universum: My Country, that showed the scenic and cultural attractions of the mountains around Salzburg and featured many local celebrities, including Annemarie Moser-Pröll. And he continues to host segments on backcountry skiing. “It’s exciting to cruise through some amazing landscapes and promote some of the most attractive spots in our beautiful country,” Maier says. “I was very pleased to find out this TV series was so much appreciated by viewers.”

Patrick Lang retired recently as the World Cup correspondent for Reuters. He wrote about Marcel Hirscher in the November-December 2019 issue of Skiing History.