His Olympic gold was only the beginning. The triumphant, sometimes tumultuous professional and personal life of the 1960 Olympic downhill gold medalist, technique analyst, resort developer, and entrepreneur of eyeglass fame. By Alain Lazard

Today in the Haute Savoie of the French Alps quietly lives Jean Vuarnet, 83, captor of the first Olympic medal ever won on non-wooden skis. Vuarnet’s downhill victory at the Squaw Valley Winter Games signaled the start of the most productive decade for the great French national ski team of the 1960s. At the time of the Games, Vuarnet had already begun to co-author, with Georges Joubert, a best-selling series of influential ski technique books. In the period 1968–1975, he directed major changes in both the Italian and French national ski teams. He spearheaded the development of France’s first car-free ski resort, and then launched an eponymous and très chic line of sunglasses, marketed worldwide. Later in life, he experienced a strange twist of events that had their beginning almost 50 years earlier.

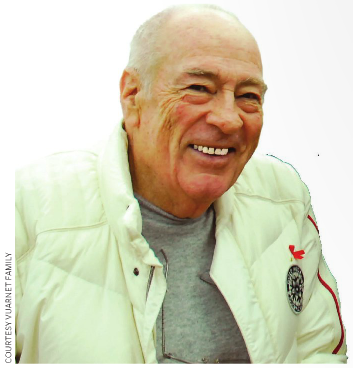

Vuarnet is dividing his time these days between the ski town of Morzine, where he was born, and Sallanches, gateway to the Mont Blanc region, where he resides in a boutique retirement home with two other residents, and his lively companion Hifi, a King Charles Spaniel. Sallanches is where the Dynastar ski company has long been headquartered. Last year, Vuarnet—just as he was recovering from hip replacement surgery—suffered a stroke. Despite this double blow, he’s determined to rebound from the ordeal.

From Law School to the Winter Games

Jean Vuarnet was born on January 18, 1933 in Tunisia, where his father, Dr. Victor Vuarnet, had recently established a medical practice. Originally from Savoie, Dr. Vuarnet soon changed his mind about life in North Africa. He returned with his family to the French Alps in 1934, settling in Morzine, one of few established French ski resorts before World War II.

Little Jean began to ski when he was two-and-a-half years old. When his father bought him his first pair of skis, he threw a fit because he thought they were too short. It was an early indication of his penchant for going straight downhill rather than wasting time with turns.

He was known by everyone in the village as Jean-Jean, the son of Dr. Vuarnet. Like the other kids, he skied and ice-skated whenever possible. He also introduced skijoring to the valley by attaching a harness to Toto, a dog that belonged to his childhood friend Roger Vadim. (Vadim went on to become a movie director and the husband, at various times, of Brigitte Bardot and Jane Fonda.)

When he finished grammar school at age 11, his father sent him to a private boarding school in Paris. He was expected to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a physician. Dr. Vuarnet exerted an overwhelming influence over his son. He encouraged Jean to pursue excellence in sports, but not to the detriment of his education. The elder Vuarnet had achieved this balance himself by attending medical school while playing soccer at an elite level, including his selection to the French national team for the 1936 Summer Games.

Vuarnet’s mother, overshadowed by Victor, had a lesser influence on him. The couple divorced when Jean was 10. His father remarried quickly, but as soon as Jean began to bond with his stepmother, his father divorced and remarried again.

As a high school student in Lyon and Annemasse, Vuarnet skied mostly during the holidays, dabbled in jumping, and became a competitive swimmer. After graduation, he decided to give ski racing a serious shot while earning a college degree. He enrolled as a law student at the University of Grenoble in 1952.

Around the same time, he became romantically involved with a young French-Canadian woman who, after she discovered she was pregnant, wrote a letter to Jean explaining the situation. The letter arrived at the Vuarnet home in Morzine. Dr. Vuarnet opened it, and then promptly decided not to reveal its contents to his son, who was away at college. Jean discovered nothing of what had happened. The girl returned to Montreal, presumably never to be seen again.

At law school, Jean joined the Grenoble University Club (GUC), where the ski program had recently been taken over by a PE teacher named Georges Joubert. It was a remarkable winter. At the French University Games, Vuarnet won the 1952 national titles in downhill, slalom and combined. He also picked up a lasting reputation as a “city racer” from his future colleagues on the French national team, mountain boys who at the time seldom pursued education beyond the age of 13 or 14.

Schooled in cities, Vuarnet was only partly raised in a ski town. He never became a true “natural” skier by his own admission. To compensate, he observed and analyzed what the best skiers were doing. Olympic bronze and silver medalist Guy Périllat expressed it well in a 2002 interview in l’Équipe Magazine: “Jean wasn’t the most gifted among us, but he always scrutinized everything in depth.”

Vuarnet’s attitude was a perfect fit with what Georges Joubert was doing at the GUC. Their first book, Ski ABC: Technique Moderne, published in the fall of 1956, was praised by 1937 overall world champion of alpine skiing, Émile Allais, who contributed a preface. The purpose of the photos in Ski ABC was to demonstrate that the world’s best racers all used the same basic techniques. That opinion contradicted the narrow nationalism prevalent in ski technique at the time, when French, Austrians and Swiss each were claiming to have the superior method.

For more than a decade, Joubert and Vuarnet analyzed and explained what they observed in elite racers, codifying their findings in five books, translated into multiple languages, which influenced ski coaching and teaching around the world. Joubert tended to focus on turning technique, Vuarnet on speed. From their books emerged inventive technique terms, such as the Jet Turn, the Serpent, Avalement (swallowing terrain irregularities), and l’oeuf.

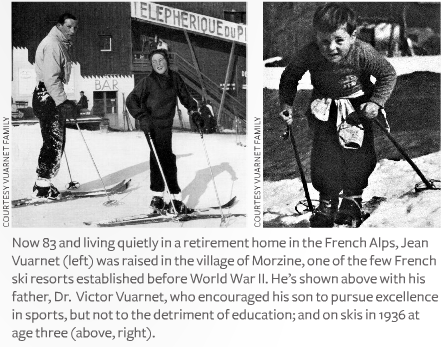

Vuarnet’s downhill research led him to an enhanced streamlining of the body, with feet farther apart for superior gliding. After he used it to win his Olympic downhill gold medal at Squaw Valley, American media called it the “egg,” which translates to French as l’oeuf. Actually, a cartoonist at the French sports daily l’Équipe, André Caza, in 1946 used the word “oeuf” in a comical way to describe the positions employed by cyclists and skiers to streamline themselves.

For Vuarnet, the correct stance was not natural. It required special physical conditioning to build the stamina necessary to hold the position for sustained periods of time. It combined the two necessities for reaching maximum speed in speed racing: a body profile offering minimal air resistance, and the ability to keep skis flat on the snow and properly loaded for the best possible gliding. The racer could employ it to gain time on the easier sections of downhill courses. Later, Honoré Bonnet, the iconic director of the French Ski Team, wanted to call the position “VJ” (Vuarnet Jean), but it was dropped for l’œuf, or aller tout schuss.

The Path to Olympic Gold

During the period leading up to the 1960 Winter Olympics, Vuarnet rose rapidly through the racing ranks, winning regional and national races and competing on the international circuit. He collected seven national titles in all three existing disciplines—downhill, slalom and giant slalom—from 1957 to 1959.

He made the cut to race the giant slalom and the downhill at the 1956 Olympics in Cortina d’Ampezzo, only to discover at the last minute that his GS spot had been given to another team member. Angry, he declared publicly that James Couttet, the French team coach and 1938 world downhill champion, “…was a great racer but a mediocre coach.” The declaration made the front page of France Soir, a daily newspaper with a print run of 1.2 million copies. Vuarnet didn’t ski in the GS or in the downhill…and Couttet resigned.

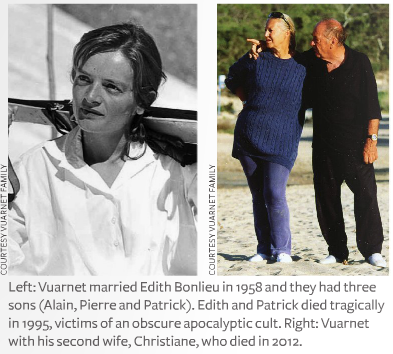

At the 1958 World Championships in Bad Gastein, Vuarnet won a bronze medal in the downhill, then added three titles at the French National Championships. That year he married the attractive Edith Bonlieu.

Vuarnet’s new bride had experienced family misfortune. She had grown up among four siblings with three different fathers, without knowing her own. One brother was 1964 Olympic GS gold medalist “Le Petit Prince” François Bonlieu, who was killed tragically in 1973. Notwithstanding these challenges, Edith became a formidable racer in her own right, winning three national titles. A leg fracture prevented her from competing in the 1960 Squaw Valley Olympics. She could console herself with the knowledge that, uniquely, she had a brother and husband who were both Olympic gold medalists. (Edith and Jean went on to have three children—Alain, b. 1962; Pierre, b. 1963; and Patrick, b. 1968.)

At the 1960 Winter Games at Squaw Valley, Vuarnet rode a pair of metallic Allais 60s made by Rossignol, designed in collaboration with Emile Allais. At the time, high-performance competition skis were still made of laminated wood. One of the drawbacks of the first metal skis produced was the lack of consistency between the skis in a pair. Vuarnet left France for the Olympics without a pair to his liking. Even with the best pair sent to Squaw Valley, only one ski performed well. He instructed Rossignol to make him a second ski similar to the one he liked… and he received it in California only days before the race! The skis were worth their weight in gold.

A New Life After Racing

A New Life After Racing

On returning from Squaw Valley, Vuarnet was greeted at home by an overwhelming reception in Morzine. He was offered the position of Director of Morzine’s Office du Tourisme, in charge of promoting the resort. He started work immediately. Also, with the aid of ski journalist Serge Lang, he wrote a book, Notre Victoire Olympique. A new life, a new career had begun.

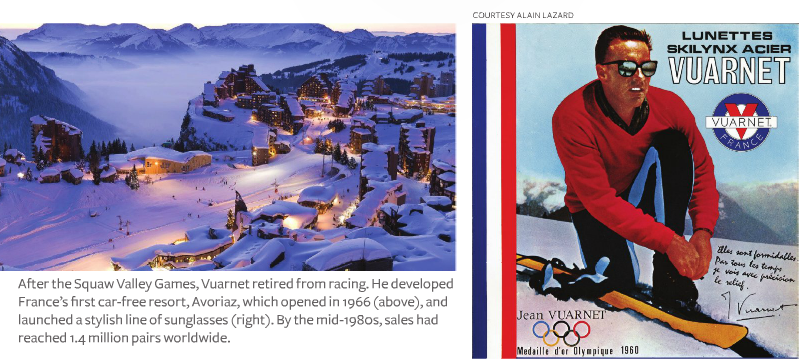

Pouilloux and another eyeglass manufacturer approached him with an offer to develop a new and stylish pair of sunglasses, called the Vuarnet. Sales were slow, but took off in the 1980s after the company was a sponsor of the 1984 Summer Games in Los Angeles, where it introduced its catchphrase, “It’s a Vuarnet Day, Today.” Newspapers compared owning a pair of Vuarnets to having an Hermès scarf. Celebrities Mick Jagger and Miles Davis wore Vuarnet glasses, as did world-class sailors and ski instructors at resorts like Cortina, Courchevel and Megève. Annual sales reached 1.4 million pairs worldwide and in the United States, Vuarnets surpassed Bausch & Lomb’s Ray-Bans for a few years in a row. France rewarded the success with the coveted Annual Export Award.

Creation of the Avoriaz Resort

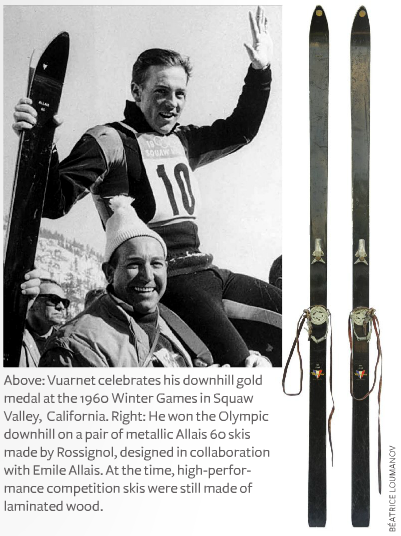

Beginning in the 1960s, new ski-in, ski-out resorts were being developed in France—among them La Plagne, Tignes, Les Menuires, Flaine and Les Arcs. As head of Morzine’s Office du Tourisme, Vuarnet envisioned a grand project—the development on an adjacent plateau of a high-altitude, pedestrian resort.

“I convinced the municipality to imagine a brand new resort above Morzine,” Vuarnet recalls, “free of cars. It would be Avoriaz.” As the possessor of a law degree, an Olympic gold medal, and knowledge of skiing and the local terrain, Vuarnet was seen as having the assets necessary to launch such an ambitious venture. The municipality gave the project 200 acres of developable land for a base village. Avoriaz, the first no-car resort in France, opened in 1966. Later Vuarnet negotiated an agreement to connect Avoriaz to 11 adjacent resorts, including four in Switzerland. Les Portes du Soleil is now the second-largest complex of interconnected ski areas in the world.

“I convinced the municipality to imagine a brand new resort above Morzine,” Vuarnet recalls, “free of cars. It would be Avoriaz.” As the possessor of a law degree, an Olympic gold medal, and knowledge of skiing and the local terrain, Vuarnet was seen as having the assets necessary to launch such an ambitious venture. The municipality gave the project 200 acres of developable land for a base village. Avoriaz, the first no-car resort in France, opened in 1966. Later Vuarnet negotiated an agreement to connect Avoriaz to 11 adjacent resorts, including four in Switzerland. Les Portes du Soleil is now the second-largest complex of interconnected ski areas in the world.

Italian and French National Ski Teams

After the launching of Avoriaz, Vuarnet anticipated devoting more time to his growing family, with two boys and a third on the way. But another challenge arose: The president of the Italian Winter Sports Federation asked him to lead the country’s languishing alpine ski team, ranked 8th in the world. The losing status was unacceptable to the proud Italians, who still remembered the great period of Zeno Colò, 1950 world champion in giant slalom and downhill at Aspen and downhill gold medalist at the 1952 Olympic Games.

Vuarnet hesitated, but finally accepted the challenge, with the condition that he be given carte blanche to run the operation as he wished. He led the team from 1968 to 1972, blessed with the arrival of 18-year-old racer Gustavo Thoeni. Success followed. Before his tenure, the Italian alpine team in 17 years had scored only one podium in the classic races. A year after Vuarnet left the team, 1973, Italy had risen to second in the men’s Nations Cup standings, and a year later first, ahead of Austria. The exceptional team was nicknamed The Blue Avalanche. Between them, Thoeni and Piero Gros won the overall crystal globe, symbolic of the best alpine ski racer in the world, consecutively between 1971 and 1975.

In 1972, Vuarnet was petitioned to accept the vice presidency of the French Ski Federation, which perceived the national team to be in trouble. Against his better judgment, he accepted, with the condition that his friend and collaborator Georges Joubert be placed in charge of the team. Despite what the two men brought to the table—Vuarnet’s just-accomplished turnaround of the Italian team, and Joubert’s transformation of an insignificant university ski club into the number-one team in France—the new assignment quickly turned sour. Their reforms were derailed. The fusion of staff, racers and suppliers, which Vuarnet had been able to create in Italy, did not happen. The French Federation, supported by the government’s Secretary of State for Youth and Sports, decided to fire six top racers for intransigence. Joubert resigned.

The mountain community and 1968 Olympic triple gold medalist Jean-Claude Killy unconditionally supported the racers, leading to a split between Killy and Vuarnet that persists to this day. It’s a long, complicated and unpleasant story. (For one version of what happened, visit www.affairevaldisere.fr; a differing interpretation will appear in the July-August 2016 issue of Skiing History.)

Vuarnet quit after two years. By 1974, he had spent almost 15 years working nonstop since his gold-medal win at Squaw Valley, with little time for family life. Edith had borne the brunt of handling the house, running two ski shops in Avoriaz and raising three boys. The only time the family spent together was during extended summer vacations in the South of France, the Costa del Sol in Spain, and aboard Vuarnet’s sailboats, the Eileen and the Tahoe, a 64-foot custom-built schooner.

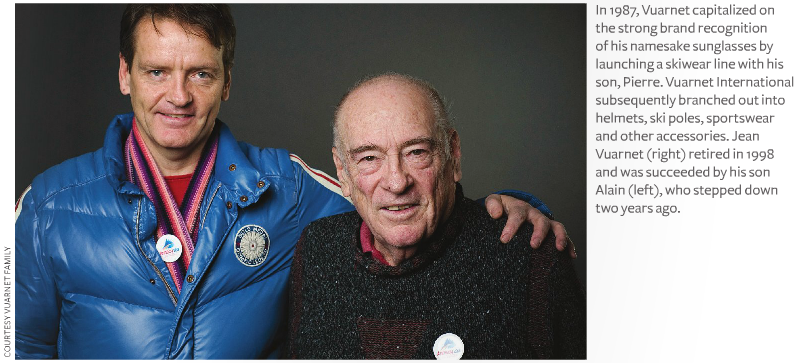

Vuarnet took advantage of this window of time to try his hand at a lifelong passion: books and reading. For a few years he launched and operated a publishing company, Les Éditions VUARNET, which handled titles as diverse as cinema, history, travel guides, sports and medicine. This semi-dilettante period didn’t last. In 1987, Vuarnet decided to capitalize on the strong brand recognition of his namesake sunglasses by launching a skiwear line with his son, Pierre. Subsequently created was Vuarnet International, which branched out into watches, sportswear, shoes, perfume, cosmetics, pens, luggage, leather goods, jewelry, ski underwear, helmets, ski poles and skis. The company came to oversee luxury Vuarnet shops in Brazil and France, and developed licensees with distribution in 30 different countries. Jean Vuarnet retired in 1998. His son Alain, who succeeded him, stepped down two years ago.

Family Tragedy

The years 1994 and 1995 were horrific ones for Vuarnet and his family. In October 1994, news emerged of a mass suicide in nearby Switzerland. The bodies of 53 members of an obscure apocalyptic cult, the Order of the Solar Temple, were found dead and partially burned. A few days later, two journalists showed up at the door of Vuarnet’s chalet in Morzine. From them Vuarnet learned that his wife Edith and Patrick, the youngest of his three sons, belonged to Solar Temple. Thankfully, they were not among the victims. But the family was devastated. Over the next year, they desperately tried to persuade mother and son to leave the sect.

The effort failed. On Christmas Day 1995, another 14 sect members were found in a remote area of the Vercors range near Grenoble, their bodies shot and partially burned. After a week of waiting, Jean learned that Edith and Patrick were among the dead. It was a terrible tragedy. Despite public outcry and civil lawsuits, a key cult leader—a Swiss musician and orchestra conductor—was inexplicably acquitted.

The funeral of Edith and Patrick in Morzine was a moving tribute to the Vuarnets from the local community and afar. Jean received hundreds of condolences from around the world. One was from a Montreal woman named Christiane. She reminded him that they had known one another in the early 1950s. By coincidence, Jean’s son Pierre was living with his Canadian wife and two children in Montreal at the time, so Jean decided to spend the 1996 Christmas holidays with them. While he was there he looked up Christiane. To his shock and surprise, she told him how she had moved to Canada and given birth to a lovely child, Catherine. In Montreal, for the first time, Vuarnet met his biological daughter, named Catherine.

Three years after re-connecting in Montreal, Jean and Christiane married. Over the next 13 years together, they divided their time between Morzine, the Baleares Islands (where Vuarnet moored his schooner, Tahoe), and a picturesque Cantons de l’Est village in Quebec, Knowlton, which happens to be the longtime home of Canadian two-event world champion Lucile Wheeler Vaughan—who had no idea another gold medalist was living nearby.

In 2012, Christiane died of a heart attack. After her passing, Vuarnet sought a place where he could spend the remainder of his years. He found a retirement home in Sallanches, then recently returned to his home town of Morzine.

Only a handful of French ski champions have accomplished so much after their successes on the slope—notably Émile Allais, Vuarnet, and Jean-Claude Killy. Vuarnet looks back at his career with pride and equanimity. Over his multi-faceted career, he made a good amount of money, “but money-making,” he says, “never drove the decisions that led to my successes.”

The author, the late Alain Lazard, was a longtime ISHA member and frequent Skiing History contributor. His most recent articles included “Rise and Fall of Racing Nations” (May-June 2015) and “Joe Marillac: The Little-Known Frenchman Who Helped Squaw Valley Win the Winter Olympics” (July-August 2013).