By Yves Perret

It was greater than his famous Olympic gold-medal hat trick. In an exclusive interview, Jean-Claude Killy recalls the first season of the World Cup, 50 years ago, when he won 12 of the 17 races, including all of the downhills, and finished on the podium in 86% of the races he entered, a record that’s never been surpassed.

Fifty years after the fact, 1967 remains one of the most memorable seasons in alpine ski competition history. Not only did it introduce the new World Cup—skiing’s first use of a season-long series of competitions to determine the world’s best—but it also resulted in an astonishing, never-to-be-repeated record.

Jean-Claude Killy of France won 12 out of the 17 slalom, giant slalom and downhill races on the calendar. He was the victor in all the classic downhills, and the Hahnenkamm and Wengen combineds, something no man has since done.

Jean-Claude Killy of France won 12 out of the 17 slalom, giant slalom and downhill races that made up the 1967 World Cup season. He was the victor in all the classic downhills, and the Hahnenkamm and Wengen combineds, something no man has since done. For the whole season, he participated in 29 races, and won an amazing 19 (66 percent) of them. He finished on the podium in 86 percent of the competitions he entered. He also won six of the season’s downhill-slalom "paper" combineds.

Killy won the first World Cup crystal trophy with a perfect 225 points, the maximum possible in a system in which a racer, who’d won three races in a discipline, could not earn more points in it. First-place was worth 25 points, compared to 100 points today. His one-man World Cup point total topped that of a whole nation—Italy, West Germany or the United States.

In 1965 in SKI Magazine, Serge Lang had crowned him with the nickname “King Killy,” a title repeated by newspapers and magazines around the world. Last summer, the “King,” 73, invited me to his home near Geneva. On the table in front of us Killy spread open neatly organized, thick albums of press clippings displaying the highlights of his exceptional career. Written in upright handwriting in the notebook containing his race results, is the sentence “La victoire aime l’effort” (Victory loves effort). Over several hours of conversation, he was once again the best skier on the planet.

INTERVIEW: Part 1

Jean-Claude, how do you look back at your 1967 season, and how did it come together after what had occurred in the previous seasons?

If the World Cup hadn’t been invented, my 1967 season might not have been what it was. It was a greater achievement than my 1968 gold-medal hat trick at the Grenoble Winter Olympics, for which most people remember me.

I got there by a slow process of building. My constant obsession was winning. I managed to pull off a couple of wins, like the Critérium de la Première Neige in 1961 when I was 18 years old. In 1963, I finished in second place 11 times. And the 1964 Winter Olympic Games in Innsbruck were a technical disaster. I lost the toe piece of my binding in the slalom. In the downhill, my edges weren’t correctly sharpened, and I fell on the first fall-away turn. I finished fifth in the GS. In short, I wasn’t ready.

The week after the Olympics I won the giant slalom of the Arlberg-Kandahar in Garmisch, Germany, ahead of my American friend Jimmie Heuga. It proved that I’d brought my skiing to a decent base, but there were still kinks to be worked out.

I hadn’t yet resolved health issues that had affected me since I suffered jaundice when I served as a 2nd class soldier in the French Army during the Algerian war. I was skinny. I lacked endurance. In Paris, journalist Michel Clare introduced me to Doctor Creff, a specialist in exotic diseases. He found out that I also suffered from

amebiasis, and helped me to recover. But I had to work a lot harder than my teammates to be in top physical shape.

I also needed a system that would allow me to be successful and consistent in not just one, but all three alpine disciplines—slalom, giant slalom and downhill. Specialization limits the opportunities to win. I wanted to develop a system that would address all of the variables that make alpine ski racing such a complex sport—equipment, start number, ski preparation, snow type, weather conditions and more.

What made a difference?

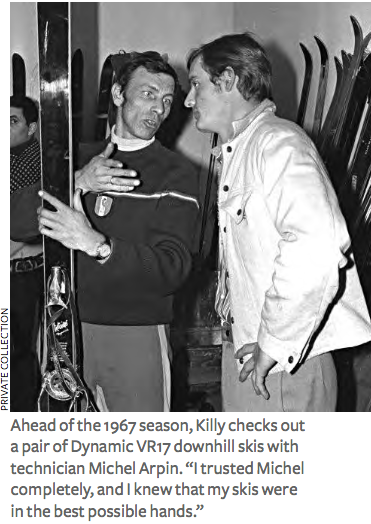

A key challenge was equipment. It’s crucial to have the best. You can’t allow yourself to lose because of your skis. I skied on two different brands, Rossignol and Dynamic, without having an exclusive contract with either company. It allowed me to choose the pair of skis that would be best for each race.

At the 1966 World Championships in Portillo, Chile, I used Rossignols in the GS, and Dynamics for the other events. In 1963, in the Kandahar, I even finished second on a pair of Austrian downhill skis. I was prepared to make financial sacrifices so that I’d be free to use the equipment I wanted.

Above all, I was helped when the Dynamic ski company hired Michel Arpin to take care of my skis. He was from the town of Saint-Foy-Tarentaise, right near my hometown of Val d’Isère. We spoke the same local dialect. Michel had an amazing practical intelligence. Like me, he’d dropped out of high school at 15. When we started our collaboration, I told him: we will make fewer mistakes because we are going to know more than the others. I trusted Michel completely, and I knew that my skis were in the best possible hands.

Describe the process that took you to the top.

As members of the French national team, we spent the whole winter together. But before the first fall training camp we each pursued our own way of doing things. I was on a personal, obsessive quest to figure out what would help me improve, fueled by an overwhelming passion for skiing focused on racing. I opted not to continue my studies. I dropped out of high school. For many young racers, it’s a questionable decision. It limits your options, and can complicate finding a career after ski racing. For me, though, racing was a healthy obsession. It didn’t lessen my ability to think on my own. My aim was to be a free man. Skiing became my profession.

Winning was all that mattered. I didn’t have a choice. It was simply my only form of expression. France’s head coach Honoré Bonnet understood that. The goal was to win races.

What were the keys to your success?

Beginning in 1965, several factors came together, fueling the French national team’s growing momentum. The organizational talent and coaching of our leader Honoré Bonnet was one factor that helped us. Another was support from French ski industry—manufacturers like Rossignol and Dynamic skis, Trappeur boots, Salomon and Look bindings. French ski resorts and hotel owners also welcomed us with open arms, charging us next to nothing for lodging and meals. The atmosphere in France at the time was incredibly supportive of ski racing.

“Our athletes are our best ambassadors,” declared France’s President General Charles de Gaulle. All of a sudden we went from the dormitories of a simple UCPA outdoor center to four-star hotels.

It was the beginning of a golden age for the sport. . . a convergence of increased financial resources, the right people, and experienced professionals. Plus, television broadcasting had gone international, transforming athletes into stars.

In 1965, after nine wins and seven second-place finishes, I was voted the Martini Skieur d’Or, and Champion of Champions by the newspaper L’Equipe. One by one, I’d assembled the pieces of the puzzle.

What was the impact of the World Cup’s creation on the outcome of your incredible 1967 season?

The specific formula and name for the World Cup didn’t come from the racers, but the idea—the force for change—did. Racers were exasperated that their entire careers could depend on a single day’s result in the Winter Olympics, or once every four years when a separate FIS World Championships were held. Nothing big happened in odd-numbered years. Careers were short. Few racers enjoyed the chance to ski in two Olympics. We often discussed our frustration, and what could solve the problem.

We were all fans of Formula 1 car racing, in which the best are determined by accumulated results over a season-long competition. So it was easy for us to embrace the plan for a World Cup of Alpine Skiing formulated in 1966 by journalist Serge Lang, collaborating with America’s Bob Beattie, France’s Honoré Bonnet, and Austria’s Sepp Sulzberger, supported by the Paris-based sport daily l’Equipe and journalists like Michel Clare—and John Fry, who added the Nations Cup to the mix.

During the August 1966 World Alpine Championships at Portillo, Chile, FIS President Marc Hodler gave it the green light. It would enable us to accumulate points in a series of races, including the classics of the Kandahar, Kitzbühel and Wengen, as well as races every winter in America. The mineral water company Evian supplied beautiful crystal trophies.

At Portillo, I remember being in the finish area of the downhill after my gold medal win. Everyone was crying. Serge Lang said to me, “The World Cup is coming. What’s your strategy going to be?”

“I’m going to fly through it,” I answered. “It’s going to be a lot of fun.” In my mind, I was going to get the most out of the new system in order to take my sports career to a new level. From then on, more than just the big classic events in the Alps would be the measure of a successful season.

How would you describe the relations among members of the French team?

We trained together and we competed against each other every weekend. Even to this day, we’re like brothers.

In the spring of 1966, we skied run after run together on the Pissaillas glacier at the Col de l’Iseran, preparing for Portillo, Chile—the only FIS World Alpine Championships ever held in the southern hemisphere. Our different strengths and personalities helped us to support each other. There was always a deep feeling of mutual respect and humility.

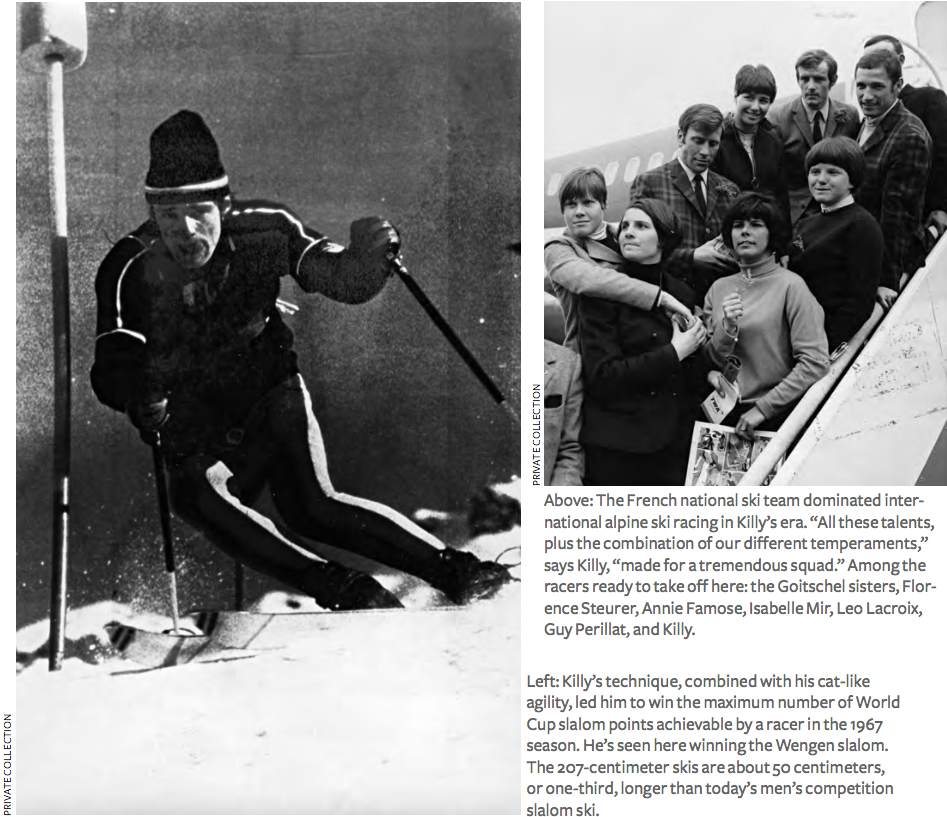

Our inspirational leader Bonnet, 47, a year away from retiring, had put in place a system that functioned superbly, both for the men and for our great women’s team at the time. Each member of the team had his own role. Michel Arpin took care of my skis and did timekeeping. I could fully rely on his technical expertise.

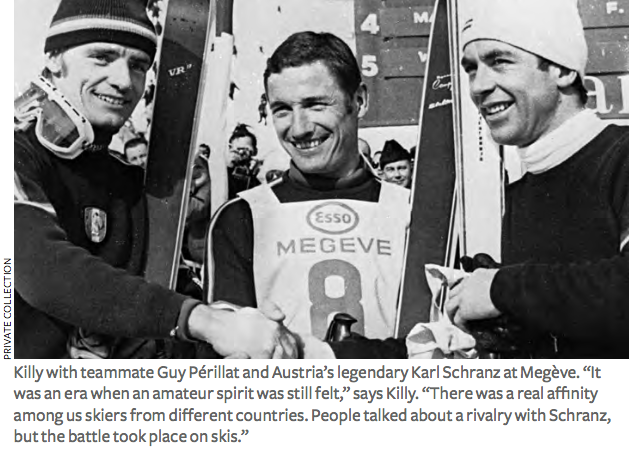

Jules Melquiond brought to the team a calm, serene temperament; we were roommates for seven years, and we never had even the most minor ego clash. Team captain Guy Périllat was listened to and respected. Léo Lacroix contributed his optimism, good humor, and especially his talent. Georges Mauduit, the giant slalom specialist, and Louis Jauffret, the slalom specialist, were magnificent skiers.

All of these talents, plus the combination of our different temperaments, made for a tremendous and cohesive squad.

The 1967 season began in December 1966 at your home resort of Val d’Isère, with the traditional Critérium de la Première Neige . . .

The race was special that year because it was the first time it was held on the new Daille run, called Oreiller-Killy or OK, which I had helped to design. (Editor's note: Henri Oreiller was 1948 Olympic downhill gold medalist.) Léo Lacroix, who won the race, still laughs when he recalls it today. “I’m the only one to have beaten Killy in downhill in the 1967 season,” he says. I remind him that it was in December 1966. The Critérium didn’t yet count for World Cup points. The World Cup didn’t begin until January 5th at Berchtesgaden, Germany, where I finished third in the GS.

Your first success came a couple of days later in the GS at Adelboden, Switzerland, the first in a series of eight victories, counting the Combined. You went on to win twice (downhill and slalom) at Wengen, also in Switzerland. What was the importance of this double win?

Your first success came a couple of days later in the GS at Adelboden, Switzerland, the first in a series of eight victories, counting the Combined. You went on to win twice (downhill and slalom) at Wengen, also in Switzerland. What was the importance of this double win?

At Adelboden, I won with the GS with bib number 13. It was no bad luck for me! Adelboden has always been a benchmark for the GS. Winning there confirms a certain level of physical training and technical skill. In any season, too, the first win is significant.

At Wengen, in the downhill on the Lauberhorn, I was 25 hundredths of a second faster than Léo Lacroix. It was the first French victory in the Lauberhorn since Guy Périllat’s win in 1961. It was even sweeter because the Austrians, who maybe thought our triumph in the World Championships five months earlier at Portillo was a fluke, were expecting us to fail. It was an important moment for the whole French team.

At Wengen I also dominated the slalom, which I felt was the steepest and hardest of the year. With this triple victory-—I won the combined—I got the impression that I was finally playing in the big leagues for good. The next week would be the incredible challenge of Kitzbühel.

In the March-April 2017 issue of Skiing History, we’ll present the second part of this exclusive interview with 1967 World Cup overall men's alpine champion Jean-Claude Killy, plus an interview by journalist Michel Beaudry with Nancy Greene-Raine of Canada, who won the 1967 women’s overall World Cup title. The World Cup is celebrating its 50th anniversary this season.

Interview by Yves Perret

Yves Perret, who heads a sports media agency in Grenoble, is the former sports editor of the Dauphiné Libéré newspaper, and was editor-in-chief of Ski Chrono.