INTERVIEW by Yves Perret

In an exclusive interview, Jean-Claude Killy recalls the first season of the World Cup, 50 years ago, when he won 12 of the 17 races, all of the downhills, and finished on the podium in 86% of the races he entered, a record never surpassed.

The winter of 1967 remains one of the most memorable in alpine ski competition history. Not only did it introduce the new World Cup—skiing’s first use of a season-long series of competitions to determine the world’s best—it also resulted in an astonishing, never-to-be-repeated record. Jean-Claude Killy won 12 out of the 17 slalom, giant slalom and downhill races on the calendar. He finished on the podium in 86 percent of the 29 races he entered.

In an exclusive interview with sports editor Yves Perret in the last issue of Skiing History (January-February 2017), Killy told about the origins of the World Cup, his motivations, and his early victories in the historic first season of the World Cup, which this year is celebrating its 5oth anniversary. Part Two is the conclusion.

Killy had just won both the downhill and slalom at Wengen, Switzerland. Now came a high point of the season—the classic Hahnenkamm competition at Kitzbühel, Austria. . .

Kitzbühel was a special moment. What was it like for you?

Competing at Kitzbühel is the most exciting thing imaginable for a ski racer. You’re in Austria, where skiing is the national sport. We were challenging the guys who embody skiing itself, cheered on by an immense crowd of spectators. I was respected, but my relationship with the Austrian public could be complicated. To relieve myself from the pressure of fans surrounding our living quarters, I sometimes would even send Jean-Pierre Augert, who looked a lot like me, to go into the crowd and sign autographs.

Winning in Kitzbühel is every skier’s dream. That year I won the downhill, the slalom, and the combined, and I became the first—and still the only—skier to achieve the double-double win in Wengen and Kitzbühel, or triple win including the combined. Nowadays we don’t realize what that represented, but winning the combined was important even if it didn’t count for World Cup points and was a mathematical point combination.

In the Hahnenkamm downhill, the world’s most difficult and dangerous, I came in ahead of the German Franz Vogler by 1.37 seconds, and I beat the course record held by Austria’s Karl Schranz.

The Kitzbühel slalom is magnificent—staggeringly varied, with sidehills and rhythm changes. The atmosphere can be hostile for rivals of the Austrian team. You have to stay in a bubble, keep concentrated, be removed from the noise and the pressure, focusing on your own run. I was the fastest in both runs of the slalom. I beat by more than two seconds the Swede Bengt-Erik Grahn, who was one of the best slalom specialists of the era.

The Kitzbühel slalom is magnificent—staggeringly varied, with sidehills and rhythm changes. The atmosphere can be hostile for rivals of the Austrian team. You have to stay in a bubble, keep concentrated, be removed from the noise and the pressure, focusing on your own run. I was the fastest in both runs of the slalom. I beat by more than two seconds the Swede Bengt-Erik Grahn, who was one of the best slalom specialists of the era.

I’ll never forget the atmosphere that weekend. The local ski instructors carried me across on their shoulders to the podium to receive my awards. This would have been unthinkable a couple of years earlier. “Superman on Skis!” headlined the Austrian daily Kronen Zeitung the next day.

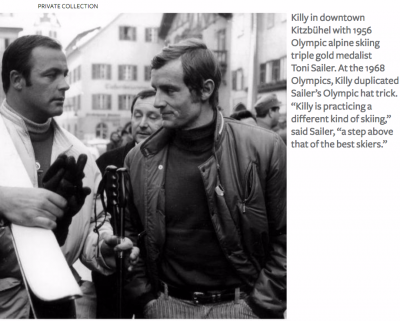

After that victorious weekend, Austria’s greatest racer, Toni Sailer wrote, “Killy is practicing a different kind of skiing, a kind of skiing that is a step above that of the best skiers. His wins are those of an all-around athlete who has reached maturity.” By then I had scored 151 out of the maximum of 175 achievable points at that stage in the season. Austria’s Heini Messner, who was in second, had 75 points.

The winning streak continued with the downhill in Megève…

The Emile Allais course was very demanding, with the Bornet face being the most difficult and dangerous section of all of the international downhill races I’d competed in. I beat the Swiss Hans Peter Rohr by two seconds. . . my best downhill ever. I was amazed by the lead. It was my eighth consecutive win. We were in the last days of January, and the 1967 World Cup downhill title was already mine.

Périllat came out ahead in the slalom. He apologized for having beaten me. He had especially wanted to beat Austria’s Karl Schranz, our perpetual rival. I was sick and I fell in the first run, but I finished second anyway, and I won the combined.

I didn’t compete in the World Cup slalom at Madonna di Campiglio, Italy. I took two weeks off. I was imitating Toni Sailer in a way. Before his triple gold medal win at the 1956 Olympics, Toni took several days off from skiing. “That’s what you should do,” he advised.

After resting, I made a comeback at Chamrousse in the February pre-Olympic races, where I won the downhill, as I would the following year in the real Olympics, when I again followed Toni’s strategy of taking a week off.

Throughout my career, I took inspiration from other top racers in order to optimize my skiing. I watched the way Adrien Duvillard carved his turns. I even copied the weightlifting exercises that I saw Soviet high jumper Valery Brummel do on TV. In 1952 at Val d’Isère when I was a boy, I watched in amazement when Italian champion Zeno Colò started so violently that the starter, who had put his hand on his shoulder, was carried down the hill.

In the weeks that followed, I continued winning. The season was about confronting each race, one day at a time. At Sestrières, Italy I won the Kandahar downhill. I liked the course and the beautiful section coming into the forest. We pulled off an all-French podium in the downhill: Killy, Orcel, Périllat. I also went away with a win in the combined.

The season ended in the USA in March. What was your experience there?

I was on a cloud. I had no doubts, no worries, no anxiety. Going to the States was something we’d been looking forward to. I was close friends with the American racers Billy Kidd and Jimmie Heuga, the son of a French Basque shepherd who had immigrated to the United States. Both were magnificent skiers. I'd met Jimmie in the summer of 1964, my first visit to the U.S. Then in 1965 and 1966 I'd competed in races organized by Bob Beattie. Nothing compared to my U.S. arrival in March 1967, though. A press conference was held when we stopped in New York. We met the governor of Massachusetts. Sports Illustrated, which featured me on its cover three times in my career, ran headlines like “Lafayette, They Are Back.” TIME Magazine hailed me “King Killy.”

I was on a cloud. I had no doubts, no worries, no anxiety. Going to the States was something we’d been looking forward to. I was close friends with the American racers Billy Kidd and Jimmie Heuga, the son of a French Basque shepherd who had immigrated to the United States. Both were magnificent skiers. I'd met Jimmie in the summer of 1964, my first visit to the U.S. Then in 1965 and 1966 I'd competed in races organized by Bob Beattie. Nothing compared to my U.S. arrival in March 1967, though. A press conference was held when we stopped in New York. We met the governor of Massachusetts. Sports Illustrated, which featured me on its cover three times in my career, ran headlines like “Lafayette, They Are Back.” TIME Magazine hailed me “King Killy.”

For me, though, the most important thing was to stay on track for the rest of the season, and finish the job.

The Franconia event was very important…

Huge crowds—thousands more spectators than had ever appeared at a U.S. alpine ski event—thronged the slopes of Cannon Mountain, New Hampshire. I won the downhill. I made the last difficult turn above the finish faster than anyone, and it was later named Killy’s Corner. I also won the GS, the slalom and the combined. I had won decisively in all three alpine disciplines, exactly like the gold medal hat trick I performed 11 months later in the Olympics at Chamrousse.

By then I was sure to win the World Cup. It was a special moment of satisfaction, though the season wasn’t yet over.

There were two more events, Vail and Jackson Hole. How did you approach them?

Winning the Nations Cup became the objective that pushed us as a team, not to give an inch. Plus, our own Marielle Goitschel had the chance to win the women’s overall World Cup, which would have been a double triumph for France. It’s always a great moment when you win as a team.

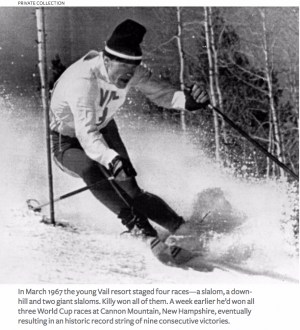

There were four races in Vail: one slalom, one downhill and two one-run giant slaloms. I won all of them. The last race, on Sunday, counting for World Cup points, was held in a terrible snowstorm.

At Vail, four or five of us shared the same room in the home of our host, Suzie Meyer. It was a fun time. From Vail, I traveled with Louis Jauffret and our friend Bernard Cahier, a famous motor racing journalist, to California, where racing car designer Carol Shelby was waiting for us in his workshop near LA airport. We flew in Carol’s personal plane to Riverside, where we drove all day long on the circuit.

After a night in Las Vegas, we went to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, for the World Cup Finals. Here two more races—a giant slalom and a slalom—would be held. I was tired; I’d had a sinus infection the previous days. In order to save energy and have a little fun, I inspected the giant slalom course in a sled! I won the race. It was amazing! Including Europe, I had just won nine races in a row—three downhills, two slaloms, and four giant slaloms.

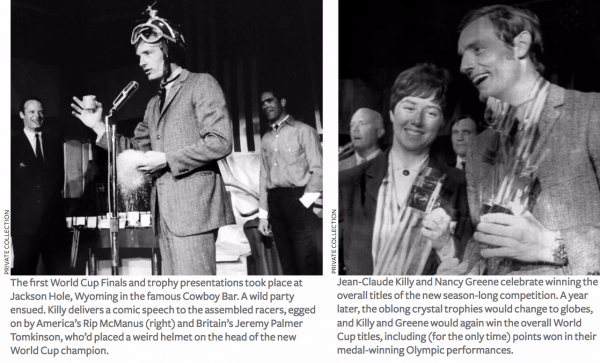

In the last race, the slalom at Jackson Hole, I DQ’d. But I had already earned the maximum World Cup points, 75, in each discipline, ending the season with the maximum possible 225 World Cup points. The Evian mineral water company, first sponsor of the World Cup, paid for my father to come to Jackson Hole, bringing with him the crystal trophy. The official presentation was held later in Evian, France.

The trophy presentation took place in Jackson Hole’s Cowboy Bar. It was preceded by a reception, with free margaritas and pisco sours for all. It was wild night. I remember that the sheriff came to make order in the streets and—I don’t know how—Marielle (Goitschel) dropped him to the floor. He finally understood who we were, and everything turned out okay.

The season was over, or almost. There were still a couple of races in Switzerland when I got home. I won a GS at Verbier, and Mauduit beat me in Thyon. But it was on the American tour that the bulk of the job was finished.

Who were your main rivals during that magic winter?

The winter of 1967 was notable for an incredible density of talent. No fewer than 14 skiers from seven different nations placed second in the races that I won. In the overall World Cup, I scored almost twice as many points as the runner-up, Austrian Heini Messner. He was a classic skier—a reserved man but consistent and hard to beat. He was followed in the standings by my teammates—Périllat, Lacroix and Mauduit—and my great buddy Jimmie Heuga. Four times during the season I’d found myself on top of the podium with Jimmie.

It was an era when an amateur spirit was still felt in the sport. There was a real affinity among us skiers from all different countries. Once on the course, we were rivals, but it didn’t alter our relationships. People talked about a rivalry with Karl Schranz, but the battle took place on skis. The rest of the time we got along really well. With all the skiers of that era, there are plenty of shared memories, moments of laughter, and anecdotes.

This incredible season generated a remarkable level of media coverage and fame. How did you handle it?

Media attention quickly came from beyond the few newspapers and magazines that typically cover international alpine skiing. After my win at Wengen, the media following us were no longer the usual ones like Paris Match and the French television show, Cinq Colonnes à la Une. The popular mass tabloids were onto us. They wanted to know everything about us. . . not just our lives as athletes. By the end of the 1967 season, the tour was a media frenzy.

Guy Périllat warned me in January, at the Tennein Kitzbühel, where we traditionally celebrated our success. He said, “Watch out, don’t get caught up in what happens around you. It brought me down after my 1961 season [Ed. note: In that season Périllat won all the downhills, followed by a dry spell that lasted several seasons.] But I know that won’t happen to you because you know how to keep things in perspective.”

With my experience of 1967, I learned how to deal with the constant presence of special correspondents from the French and international press. I had to be able to open the doors, then close them. That was also what I did the following Olympic season in Grenoble. A 30-minute press conference every day and that was it.

The American tour proved hugely rewarding for me. I had offers from sports agents. I was offered $200,000 to join the professional circuit and manage a ski school in the States. A lot was expected of me, but I had to stay focused on the Olympics the following year.

When did you become aware of the exceptional nature of the 1967 season?

I never really grasped it entirely. I didn’t realize what I’d achieved. Of course, there were the numbers: winner of 19 races out of 29, including 12 World Cups out of 17, and seven of the season’s combineds for a total of 26 first-place finishes. But I never said to myself, “Wow, that’s fantastic!” It’s taken me 50 years to realize how remarkable it was.

In Grenoble in 1968, by comparison, things were actually relatively simple. There were three races within a set period of time, at a date identified well in advance, with an objective that was fairly clear. The 1967 season was a more complicated, elaborate construction. Comparing them is like comparing a sprint and a marathon.

In the summer of 1967, I quickly moved on to something new. I had an overwhelming passion for motor sports. I won The Targa Florio with Bernard Cahier and drove 1000 KM of Monza, the 24 hours of Le Mans, and the 1000 KM Nurbürgring behind the wheel of a Porsche or an Alpine. It was good to experience other sensations, and new challenges. Now, 50 years later, I’ve had the pleasure of revisiting this incredible season at the request of Skiing History. Thank you!

Yves Perret, who heads a sports media agency in Grenoble, is former sports editor of the Dauphiné Libéré newspaper, and was editor-in-chief of Ski Chrono.