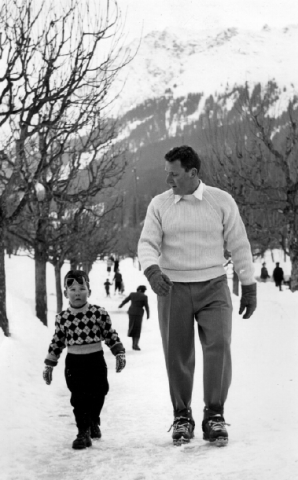

Above: Adam and Irwin Shaw in 1953, walking into the village of Klosters.

Irwin Shaw (1913–1984) was an American writer. He’s best known for his novels The Young Lions, whose film version starred Montgomery Clift and Marlon Brando; Rich Man, Poor Man, adapted into the first-ever television mini-series; and short stories such as The Eighty Yard Run, Act of Faith, and Girls in Their Summer Dresses. His seminal anti-war play Bury the Dead, originally staged in 1933, is still produced around the world today.

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Shaw saw action in North Africa, France and Germany during World War II. He moved to Europe in the early 1950s with his wife Marian and young son Adam, living first in Paris before discovering the Swiss village of Klosters, which he made his permanent home. In this article, Adam remembers the days when the sport was simpler and the Alps were studded with stars who didn't take themselves seriously.

By Adam Shaw

All photos courtesy Adam Shaw / www.irwinshaw.org

In the angry days through which the world was passing, there was a ray of hope in this good-natured polyglot chorus of people who were not threatening each other, who smiled at strangers, who had collected in these shining white hills merely to enjoy the innocent pleasures of sun and snow…The feeling of generalized cordiality…was intensified by the fact that most of the people on the lifts and on the runs seemed more or less familiar…Skiers formed a loose international club and the same faces kept turning up year after year. —Irwin Shaw, “The Inhabitants of Venus”

My father wrote this in 1962. A week later, in the middle of the Drostobel—one of the seriously steep runs that rise above Klosters—he whacked me across the back of the legs with a ski pole.

He was 49 and in his prime, I was 12. He’d never hit me in anger before, and he never would again. I’d cut to a stop above him on a patch of ice, and clipped his skis. He’d grabbed a piste marker, but I’d slid a quarter of a mile down to the Drostobel’s tree line.

He bulled his way down the run to me. “You coulda killed us!”

I stared at the tips of my Kneissls, a gift from a rotund Frenchman who designed cars, some of them famous.

“Showing off,” Irwin shouted. “That’s what happens when you show off!”

Before Prince Charles and other “royals”—not to mention Hollywood stars like Greta Garbo, Gene Kelly, and Lauren Bacall—brought a certain kind of newfangled fame to Klosters, it was just another village with a few ski lifts…nothing fancy like St. Moritz, Gstaad, Cortina or St. Anton. And for me, it was just home—the place where I grew up.

Irwin at the top of the Gotschnagrat above Klosters with fashion model Bobby Charmoz.

Irwin at the top of the Gotschnagrat above Klosters with fashion model Bobby Charmoz.When my father and mother bought a half-acre of hay field from Mr. Brosi in 1955 and built a house there, cows outnumbered people. Chalet Mia (named for the three of us, Marian, Irwin and Adam) had pink shutters—the locals thought this was nuts—and one side of the roof was longer than the other, in the Basque style. It would be the only house they’d build in their lives. We all learned to ski on wooden Attenhofers, with screw-on edges and bear-trap bindings. Then Walter Haensli, a neighbor and ex-ski racer who married an American heiress, got the right to import Head skis. My parents each got a pair, and I borrowed my mother's—black with white lettering—to win my first race at age seven.

The old man had spent a few unmemorable days in Sun Valley right after the war. But now, patient souls by the name of Hitz and Clavadetscher got him back on track: “Ya, Herr Shaw…mitt de knees you must go DOWN und den UP, und den down mitt de knees…Und de shoulders, de shoulders must be looking down de mountain…down.”

In those days, skiing was as much a voyage as a sport, and that appealed to the old man.

Imagine growing up dirt poor in Brooklyn before the Great Depression. Imagine landing in Normandy in 1944, and liberating the Dachau concentration camp. Then imagine standing on top of the Gotschna on skis, and with a newly built chalet visible down in the valley.

Imagine standing there with Peter Viertel, your old buddy from California, and Jacques Charmoz and Moshe Pearlman. Peter saw combat with the U.S. Marines in the South Pacific and later ran agents into Germany for the OSS; after the war, he was a screenwriter and novelist. Jacques raced for France in the 1936 Winter Olympics; during the war, he was a pilot in the Free French Air Force and, later, flew the last French general out of Dien Bien Phu. A British major who risked being shot for treason for helping Israel get guns, Moshe later served as David Ben Gurion’s first spokesman and wrote a book on archeology called Digging Up The Bible. Imagine their disbelief, their sheer sense of luck, and of joy, at simply being on top of a Swiss Alp, alive after the war and with all body parts intact.

Left to right: Actor Noel Howard, an unidentified friend, Marian and Irwin Shaw, Jacques Charmoz and Jacqueline Tesseron on the slopes of Parsenn.

Left to right: Actor Noel Howard, an unidentified friend, Marian and Irwin Shaw, Jacques Charmoz and Jacqueline Tesseron on the slopes of Parsenn.Over three decades, the group at the top of the Gotschna, or at our dinner table, included Swissair pilots, Kiwi sailors, regal Spaniards, French ex-Prime Ministers, ambassadors sitting out diplomatic storms and barons of industry, who, before the term was coined, showed off their trophy wives. I remember well the Greek shipping magnate whose most beautiful daughter was destined to tragedy, and various spies whose covers as bankers or businessmen fooled no one. There were, of course, actors with Oscars, agents with chutzpah, writers who could ski and writers who could write—like James Salter, who could do both in a class quite his own (Downhill Racer, The Hunters, Solo Faces, A Sport and a Pastime). And, at one time or another, almost everyone met Dr. Egger, a truly fine and old-fashioned doctor who, faced with broken bones, first would whip out his stethoscope and say: “Ya, now you inspire, and now you expire…”

On some winter afternoons, on the mild slopes of Alpenrösli or Selfranga, you might find a Harvard professor whose Nobel Prize did nothing for his balance, or various “belles,” including one particularly well-known for her Mafia ties. You’d recognize many of them, like Virginia Hill, the ex-girlfriend of mobster Bugsy Siegel, but I think name-dropping is like blowing your nose with stolen money, so you’ll just have to take my word as to the others.

Adam Shaw at the top of the Gotschna above Klosters last winter. He now lives in the French Alps

Adam Shaw at the top of the Gotschna above Klosters last winter. He now lives in the French AlpsFor Irwin, no matter how glorious the weather, how deep the fresh snow, mornings were meant for the typewriter. Skiing en famille began at noon, in front of a wood chest in the front hall, with a grab to retrieve mittens, goggles and wax. We’d then latch our skis to a rack on the back of a VW Beetle and grind up the hill past the old Hotel Pardenn, turn left at Nett’s grocery store, turn right onto the Bahnhofstrasse, past Mr. Meilhem’s bank and APorta’s bakery, left again at the Chesa, and right at the old Apotheke to park at the Luftseilbahn.

Depending on who was around at the top, and their skiing ability, the decision was taken to traverse over to the Furka and ski down to Küblis, or, if the visibility wasn’t good, to make the shorter run down Kalbersass through the pines, to the Schwendi. With the callowness (and legs) of youth, I called that "social skiing," pleading for the Drostobel or the Wang.

The Gotschna and the Parsenn, and later the Madrisa, were our local playgrounds. Skis were long, and runs were not flattened into antiseptic boulevards by snowcats. To enjoy the virgin faces on the north side of the Weissfluhgipfel, down towards Fondei, or the steep chutes and glades down the backside of the Bramabuel in Davos, you had to know how to turn ‘em both ways. In those days Klosters was to St. Moritz and Gstaad, what Montauk was to Southampton.

For the old man, skiing was also a reward for pages batted out on his green Olivetti portable. Unlike handball, which he had played in Brooklyn and at which he was awfully good, skiing gave him time and space to work up a sweat without points or scores. Everyone was a winner on the mountain.

Irwin (far right) and Marian Shaw (far left) in Klosters in the 1960s with the writer Peter Viertel (black hat) and film director Bob Parrish (red and blue parka). Everyone in the group was on Head skis that day.

Irwin (far right) and Marian Shaw (far left) in Klosters in the 1960s with the writer Peter Viertel (black hat) and film director Bob Parrish (red and blue parka). Everyone in the group was on Head skis that day.If one of the chums at the top of the cable car—often Robert Ricci of haute couture renown or Freddy Chandon (you’ve surely drunk his champagne….)—had a ski teacher in tow, they’d choose the runs. If not, the best skier took the lead.

I still remember the bite of good edges on spring snow on March mornings in the late Sixties, between the Meierhoff shoulder and Totalp, with the grip then mushing into a spray of slush at the front side of a shoulder. This was before the freak avalanche passed under our feet and took out the train and the road leading to Jakob Kessler’s terrace at Wolfgang.

It was an innocent era. No one except downhill racers wore helmets, the Casa Antica opened with 45s lent by Marisa and Berry Berenson, Angelica Huston wasn’t a star yet, John Negroponte was years away from telling tall tales at the United Nations, and Joël De Rosnay didn’t know he’d be a world-famous scientist. The big lip (Minsch-Kante) below the Hundschopf on the Wengen downhill wasn't yet named for Klosters' station-master son, Josef Minsch, because he hadn't crashed there yet. But Salka Viertel already made the best chocolate cake in the world, even if Deborah Kerr or Orson Welles were not coming to tea that afternoon.

In the Seventies, the group had a few more birthdays in the legs and knees, and the choice of runs reflected this. One day, on the way to Serneus, Annie, Geza Korvin’s wife—he’d played the Captain in the 1965 movie Ship of Fools—fell into a small ditch, followed in close order by Peter O’Toole’s British brother-in law. The tall Englishman lay there, flopped down on top of her, quite unable to move. After a while the lady firmly said: “Derek, either f*** me, or get off of me!”

In the summer there was tennis on the red clay courts opposite the Silvretta Hotel, and picnics up near the Vereina glacier. Summer was the season for Garbo’s walks along the Landquart torrent with a straw hat over her ears and an incongruous “frowner” on her nose. One day, at lunch, she girlishly insisted on calling one of America’s most brilliant, and controversial, writers “Vigoredal” as though she didn’t know who he was. Gore loved it.

My father had a hip replacement operation in 1979, and we skied one last time the next winter. Savvy old athlete that he was, he knew when the legs couldn’t be trusted, so he quit. But until then, though he loved powder, he skied his best in the spring, on corn snow, with a whole hill for space and no goggles to fog up. On such Klosters mornings the world was just wind in his face and sun on his back; talent felt inexhaustible, good reviews seemed guaranteed, and wives were deemed faithful and friends true.

Adam Shaw is a freelance writer, ex-reporter for UPI and the Washington Post, and author of Sound of Impact: The Legcy of TWA# 514. He lives in the French Alps and works as a flight instructor and mountain and airshow pilot.

To learn more about Irwin Shaw, visit www.irwinshaw.org. You can see photos of Shaw’s skiing life in Switzerland on the “Klosters” page, and on the “Memories” page, you can read an excellent profile on Adam and Irwin Shaw, titled “Rich Man, Poor Man, Beggarman, Skier” (Skiing, October 1977). One of Shaw’s best short stories, The Inhabitants of Venus, can be found in The Ski Book (Bookthrift, 1985).