Bode Miller learned to ski on slopes that his grandparents, Jack and Peg Kenney, cleared after World War II on the family's New Hampshire land. From interviews and journals, the author tells the tale of a small ski area with a big legacy. By Nathaniel Vinton

Brochures courtesy Jo Kenney

Brochures courtesy Jo KenneyJack Kenney (above, in an undated photo) started Tamarack Lodge in December 1946 with a rope tow and a single slope. Photo courtesy of the New England Ski Museum

The ruins of the old ski area have been all but absorbed by Kinsman Mountain. All that remains to memorialize those long-ago New Hampshire ski days is the rusty steel guts of an old car engine that had powered a rope tow. Mike Kenney says it’s a Ford Model T, and an automotive historian would probably marvel at the brittle belt still hanging on as the moss and pine needles creep in.

It is an artifact of a ski area that U.S. alpine racer Bode Miller’s grandparents tried to establish on land they bought in the town of Easton almost 70 years ago. The motor is tipped over on its side, split into two main pieces. It rests in a small clearing on the family’s storied property, right by the Franconia town line.

The most decorated male ski racer in U.S. history learned to ski, at age two, just down the trail in the yard behind the family’s Tamarack Tennis Camp. From there, it was three quarters of a mile up a different trail to Turtle Ridge, the off-the-grid cabin his parents built in 1974. (It has recently been renovated and is now home to Miller’s younger sister, Wren, and her family.)

Miller was born in 1977 and spent every winter skiing, sledding or otherwise navigating the icy paths on his family’s rural property. In 1992 he went off to Carrabassett Valley Academy in Maine, and then to global fame. Now he is 37, aiming to give Kitzbühel another shot in 2015. Recovering from November back surgery, he expects to compete in February in the FIS World Alpine Championships in Beaver Creek, Colorado.

When he’s not traveling, Miller now lives in California, but he was back at Tamarack on August 23, 2014, hosting a golf-and-tennis fundraiser for the Turtle Ridge Foundation, his charity supporting adaptive and youth sports programs. In the doubles tournament Miller was paired with his father, Woody. Meanwhile his mother, Jo, agreed to lead me up to see evidence of the ski area her parents had tried to launch.

Jack and Peg Kenney had gotten to work on the endeavor in 1946, shortly after purchasing 450 acres, a farmhouse and the barn. The Kenneys possessed an irrepressible entrepreneurial spirit and were avid skiers. Peg—her maiden name was Taylor—had been a racer with Olympic aspirations. They hoped to draw tourists up to the Franconia area. (Jack's original partner in the venture was a Navy friend, Bob Allard; Kenney bought him out after the first season.)

“If you took this innkeeping business seriously you would be charging into a padded cell in less time than it takes for a cancellation,” Jack wrote in a diary entry dated December 12, 1946. “Your worries encompass every thing from the major item of snow to trivia such as how the pie will turn out. I honestly don’t see how a serious-minded person could last long. Your nerves would snap.”

Just six miles away was the Cannon Mountain tramway, built in 1938. Adjacent to that was the Mittersill ski area, established a few years later by Austrian Baron von Pantz, whose resort would boast of colorful European ski instructors like Sig Buchmayr and Swiss born Paul Valar. But the Kenneys were hoping to draw people to their little inn and ski slope, and Jack’s journal entries are full of pride and romanticism.

“We are ideally suited for this life as we have a sense of humor and we can see how little control we have over the elements and the fortunes,” he writes. “You are whipped mercilessly by so many things: the weather, high prices, cancellations, etc. It’s an ever-changing business and very uncertain.”

The diaries are now in the possession of the eldest of Jack and Peg’s five children, Jo. She was born in 1949 and now lives in her parents’ funky old house in the woods above Tamarack. She says her parents were “doing what they wanted to do” and were “not really concerned about what the upper classes thought."

“He charged a dollar a day, I think,” Jo says of the ski tow. “He writes about it in his diary, which is hysterical. He wrote articles in the Boston Herald for years—funny things. He was really into promoting the area. North Conway at that point had all the light, and Stowe.”

The remains of the rope tow were something I’d heard about while doing research for my new book, The Fall Line (see page 35). The book tells of Miller’s unlikely rise to the top of alpine skiing, but although Miller thrived as an outsider on the World Cup, he inherited a rich skiing tradition.

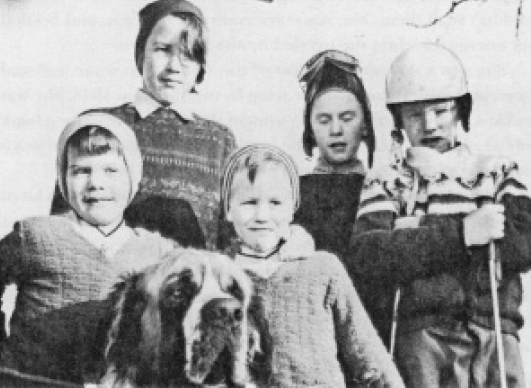

Jack and Peg Kenney's children—from left to right, Jo, Billy, Davey, Bub and Mike— grew up on the Tamarack property. Mike raced on the U.S. Pro Tour and today is Bode's mentor and primary coach. Photo courtesy Jo Kenny.

Jack and Peg Kenney's children—from left to right, Jo, Billy, Davey, Bub and Mike— grew up on the Tamarack property. Mike raced on the U.S. Pro Tour and today is Bode's mentor and primary coach. Photo courtesy Jo Kenny.“It’s probably the richest ski culture in the country, in this area, where I grew up,” Miller told me at the Tamarack event last August. “Everyone around here knew about racing. It’s a bit like being in Austria. Within my family, my uncles made it to pro, so we always had this thing where it wasn’t like racing was something that just kids did.”

The Kenneys were avid skiers—Jack a Dartmouth graduate, and Peg an Olympic hopeful. Their kids all became skilled and dedicated skiers. When Bode was growing up, his uncles and other family members could explain to him the different echelons and qualification measures that governed American skiing. (Two of Miller’s uncles, Peter and Mike, both raced on the U.S. Pro Tour; two other uncles, Bill and Davey, were also skilled and dedicated skiers.)

“It was clear there were steps all the way to the top,” Bode recalls.

Helping young Bode get up some of those critical early steps was his grandmother, Peg. When Bode was in his early teens, she loaned him money at the start of each winter for season passes at Cannon Mountain, where he would spend truant days skiing alone, discovering his distinctive turn.

“Two hundred and sixty bucks," Miller recalls of the loans, which he’d pay off fixing the Tamarack courts. “I’d pull tennis court nails on our clay courts, and roll up the lines, and sweep the courts and fix fences and mow lawns. She’d end up paying for the whole thing, but I ended up paying for usually about half of it, but I was usually one season behind.”

In his 2005 memoir Go Fast, Be Good, Have Fun, Bode Miller writes about how his grandparents “met on skis” in late 1944 at Sugar Bowl, California, with Peg just out of UC Berkeley and Jack on leave from the Navy, having seen action in the South Pacific. Within two years they were at Tamarack, trying to inaugurate their little ski area.

“I had a fine time laying pine boughs across gullies over roots on the bottom of the ski slope,” Jack Kenney writes on December 1, 1946. “Cut out some of the hill to the left of the tow—I think that is going to be a fast, interesting run.”

Jack Kenney (far left) on the snow-covered tennis courts at nearby Mittersill in 1951, during a fundraiser for the 1952 Winter Olympics ski team. He played with (left to right) U.S. tennis champion Pancho Segura, Chilean tennis player Ricardo Belbieres, and New York society columnist Cholly Knickerbocker. By 1952, his Tamarack ski lodge was struggling and Kenney has started to plan a tennis camp on the property. Photo courtesy of New England Ski Museum

Jack Kenney (far left) on the snow-covered tennis courts at nearby Mittersill in 1951, during a fundraiser for the 1952 Winter Olympics ski team. He played with (left to right) U.S. tennis champion Pancho Segura, Chilean tennis player Ricardo Belbieres, and New York society columnist Cholly Knickerbocker. By 1952, his Tamarack ski lodge was struggling and Kenney has started to plan a tennis camp on the property. Photo courtesy of New England Ski MuseumThe same entry describes his fears about whether the new rope tow will work. There are mechanical adjustments to make, and he has a feeling it won’t work, but he accepts reservations anyway.

“A party calls long-distance from Boston to reserve 6 in the bunkroom after Christmas,” he writes in the same entry. “Call Joe about 5 cord of slabwood at $7 per cord—he can’t hear me. We all get laughing and I scream at him. Peg comes up to the room pulls over her pants and jumps into bed with me and we love—she asks me if I’m happy. I am and very serene. She is happy but a worrier.”

The Kenneys prepared food at the farmhouse and did what they could to ready the slopes despite early-season fears over inadequate snow. They sent out marketing material—“Excellent Skiing, Outstanding Food, Gay Informality,” their brochure read. And they enlisted friends to help them build a small wooden structure meant to house the rope tow’s engine and offer skiers a little mid-mountain retreat.

In Jack Kenney’s diaries, mixed in with the food bill totals and worries about snowfall, there is just enough time for reflection, as is the case on January 5, 1947. That day the rope tow finally starts working properly, and Jack records “a sudden surge of satisfaction and joy” over what they are accomplishing.

“Life can be beautiful! It even is at times,” he writes that day. “Today at about 5 p.m. the first person hoved into view coming up on the enigmatic rope tow. What a thrill that was. We have been moaning, sweating, belaboring and bitching about that damn thing for weeks.”

This comes under an entry topped with jubilant block letters: SKI TOW RUNS!! GROSS INCOME FOR TWO WEEKS: $1021!! He records his vision of a fully operational ski area, presumably with his ski-racing wife offering personalized lessons. The ski area doesn’t have a name; it’s simply part of Tamarack Lodge.

“Now imagine what will happen if we get the ski tow operating, the warming shelter going and ski lessons continuing,” he writes on January 5, 1947. “We will have five sources of income: the lodge transportation, ski tow, ski lessons, and the warming shelter (sandwiches, hot drinks and other food).”

The ski area was a constant struggle, and Tamarack’s other facilities were under-utilized in the summer, so by 1952 Jack and Peg had envisioned the tennis camps. They had the market to themselves, and within a few years the Tamarack Tennis Camp was the family’s main commercial focus, along with a tennis court building-and-maintenance company that’s still going strong. They shut down the ski area sometime after the late 1950s.

Today Tamarack Tennis Camp is thriving under leadership of Wren and her husband, Chuck Weed—whom she met at the tennis camp when they were 10—along with the rest of the family. In addition to the regular seven-week summer camp season, they offer tennis weekends for adults, host the Brandeis College tennis team for a fall training weekend, and rent the lodge for two weeks in January to the University of New Hampshire ski team, which trains at Cannon.

After all these years, the place retains a rustic, low-key vibe. It was recently lauded in an article for The New Republic by Michael Lewis, the acclaimed author of Moneyball and Liar’s Poker, who wrote that Jack Kenney “ran his tennis camp less as a factory for future champions than as an antidote to American materialism.”

Future ski historians will owe a debt to Jo Miller, who rescued many of the trophies, papers and other mementos of her son’s nearly 20-year career in elite, professional ski racing. At her home she keeps scrapbooks full of early press clippings, award certificates and curiosities. She also arranged for Bode to display five of his six Olympic medals and three World Cup trophies at the New England Ski Museum, adjacent to the base of the Cannon Mountain tram.

On a piece of paper from a 2001 training session in New Zealand, a coach has recorded Miller’s times on a full-length GS course as he edges out his teammate Erik Schlopy; another scrapbook contains a 2006 article from an Austrian men’s magazine featuring one of Miller’s ex-girlfriends in her underwear, ice cubes balanced in her cleavage; and there is a U.S. Ski Team worksheet—a five-year-plan that Miller’s coaches made him fill out at age 22; in the final box, he has written a simple goal: “stay the ultimate one!”

Skiing is still a family affair to Bode Miller, and perhaps even more than ever. His primary coach on the U.S. Ski Team staff—if an athlete as intensely independent as Miller can be said to have a coach—is his uncle, Mike Kenney, who is known on the World Cup for climbing tall trees along the tour’s downhill courses to get better footage of his nephew and other team members for the scientific digital video analysis that is part of modern World Cup strategy.

Miller has also made a point of bringing his young children to see him race. When on the World Cup with him they might stay in his luxurious motorhome; the chauffeur typically parks the bus in the television truck compound near the race finish. Both children were also with him at the August charity function.

“The tennis camp was very firmly established by the time I was here,” he says. “The fact that [my grandparents] were ski lodge entrepreneurs was lost on me. The rope tow, I didn’t really know about that until I was older.”

Photo above: Bode Miller, shown here during the 1996 U.S. national championships, learned to ski at age 2 on the trails at Tamarack. Courtesy New England Ski Museum.

Photo above: Bode Miller, shown here during the 1996 U.S. national championships, learned to ski at age 2 on the trails at Tamarack. Courtesy New England Ski Museum.It’s true that the skiing culture ran deep in the Easton Valley. Cannon Mountain hosted World Cup races during the tour’s inaugural 1966–67 season. Sel Hannah, one of the founders of the American ski industry, lived nearby; one of his daughters, Joan, won bronze in giant slalom at the 1962 world championships. In 2005, Miller bought the Hannah family’s 630-acre potato farm in Sugar Hill, but he sold it recently after putting considerable improvements into the property.

The U.S. Ski Team recently signed on to invest in alpine racing infrastructure at Mittersill, which was resurrected in 2009 after lying dormant for decades. More than $3 million will go into snowmaking and trail building as part of an agreement with the Franconia Ski Club, Cannon Mountain and the Holderness School.

The national team wants it to become a center for serious super G and even downhill training, in case there’s another original talent out there in the woods, just waiting for the right opportunity. No one is expecting another racer like Bode Miller to come along—he’s a one-of-a-kind talent. Then again, he doesn’t need replacing yet anyway. He’s still got a few more races left in him—a few more chances to shake off the rust and represent Kinsman Mountain on the world stage.

Nathaniel Vinton is the author of The Fall Line: How American Ski Racers Conquered a Sport on the Edge. The book is being published in February 2015; for a review, see page 35.