In 1964, the Kokanee Glacier gave birth to Canada’s national ski team.

Canadians fared poorly at the 1964 Olympics in Innsbruck. Only Nancy Greene had a top-10 finish (seventh in downhill). In May 1964, former Canadian downhill champion Dave Jacobs, who had retired with a broken leg in 1961, wrote a letter to Bill Tindale, then president of the Canadian Amateur Ski Association (CASA), concluding: “We have some tough problems to solve which require some slightly revolutionary solutions.”

to the Kokanee cabin. Photo courtesy

Nancy Greene Raine.

Jacobs had experienced firsthand Canada’s dysfunctional ski racing program and witnessed the hugely successful programs of European nations. France, Austria and Switzerland had full-time coaching staffs, dedicated national teams with scheduled training camps and established programs for younger skiers to advance to the national level.

Canadians, by contrast, trained at their own hills, then gathered for a selection camp before major international events. CASA would then hire a European coach to join the team when it arrived at the events. This arrangement seemed to work for brilliant skiers like Lucile Wheeler and Anne Heggtveit, but it wasn’t a plan for consistent success. When Jacobs and his Canadian teammates arrived in Germany en route to the 1958 World Championships in Bad Gastein, Austria, they had never even met their coach—German Mookie Causing—and Causing certainly knew nothing about the Canadians.

It was time, Jacobs said in his letter, for Canada to develop a national team program, in which skiers could attend university on scholarship and train year-round with a full-time coaching staff. Unbeknownst to him, a small group of forward-thinking individuals were already working on just such a program. In Montreal, Don Sturgess, chairman of CASA’s Alpine competition committee, and B.C.-based John Platt, vice-chairman, had already agreed that drastic changes were needed. Meanwhile, in Nelson, British Columbia, Notre Dame University (NDU) President Father Aquinas Thomas and athletic director Ernie Gare had just implemented Canada’s first university athletic scholarship program, for its hockey team.

The four men saw plenty of common ground that could benefit both CASA and NDU.

Sturgess replied to Jacobs’ letter, saying CASA was likely to set up a national program in Nelson that year and, by the way, would Jacobs be interested in the head coach job? Jacobs eventually accepted the offer, with half his $6,000 annual salary paid by the association and half by Notre Dame, where he was employed to teach freshman math. Peter Webster took a leave from his banking job to serve as pro bono team manager, although he did receive $1,800 annually from the university to also serve as dorm supervisor.

So in the summer of 1964 Jacobs and Webster welcomed 15 men and 10 women to their new homes—the dorm at NDU—where the intense East-versus-West rivalry eased and one truly national team evolved.

Jacobs introduced high-intensity dryland training in preparation for hikes to nearby Kokanee Glacier for summer training, an experience few team members would forget. “You had to carry all your stuff in this backpack, and it was at least a three-hour hike that was quite rugged,” recalls Andrée Crepeau. “When we got to the top, some of the girls were in these tiny cloth sneakers and there was a foot and a half of snow and it was dark, completely dark.”

Courtesy CASA.

“We had those Keds, little canvas shoes,” adds Nancy Greene. “We used to go and get them at Kresge’s for a dollar forty-nine. The second year we got running shoes.”

“The boys had gone ahead, so we at least had a path in the snow to follow,” continues Crepeau. “It was kind of scary, but really exciting, and when we finally got to the cabin, wow! We were all on the floor of the top floor, no mattresses, nothing, people farting, snoring. It was such an adventure. I was a shy, well-bred little girl. I had turned 17 a couple of months before so it was quite a discovery. I loved it.”

“Each morning at 6:00 a.m. we hiked, skis on our backs, up to the glacier,” says Barbie Walker. There, a cable drag-lift awaited them, with a gasoline engine powerful enough to haul only one skier at a time. Each skier carried a tow harness that clipped to the cable. “That came in very handy to use as a tourniquet when coach Bob Gilmour, wearing shorts, sliced his calf deeply,” Walker recalls. “That accident was at 10:00 a.m., and we built a tent shelter out of ski poles and jackets to shield him from the hot sun. Currie [Chapman] ran down to the parking lot where the buses say, but, alas, the porcupines had eaten the rubber tires. He had to run further, to Kaslo, only to discover the helicopter was in Cranbrook for repairs. Four hours after the accident, Bob was riding beneath a helicopter on his way to the hospital in Nelson.”

After a day of hiking and skiing, the reward was a swim in the frigid glacier lake, followed by a sauna, sort of. Keith Shepherd, Currie Chapman, Peter Duncan and Rod Hebron had found an old pot-belly stove that they incorporated into the makeshift sauna. “Three walls of plastic on a frame against a flat rock, with a flap for a door, made warming up after the swim enjoyable,” says Walker.

With all of the hiking and just the one-person lift, Crepeau said the skiers only got in about four runs a day. “I sort of said, what am I doing this for? Am I really going to learn something with four runs?” Indeed, the skiers did learn, and it showed in their results.

“We went to the first races in 1965 in Aspen,” Jacobs says. “Billy Kidd and Jimmy Heuga had just won their ’64 Olympic medals. And Peter Duncan, Nancy Greene, Bob Swan ... they pretty much cleaned those guys. Sports Illustrated wrote this big article, ‘Canadians Raid Aspen.’ And it took off from there.”

Jacobs left the team after the 1966 season to work for Bob Lange. In 1967, Greene won six individual races and the first-ever women’s overall World Cup title. A year later she defended that title and won Olympic gold and silver as well. At the time, critics said she would have won even without the program.

“For me it was the perfect situation,” Greene says from Sun Peaks Ski Resort, where she is director of skiing and operates Nancy Greene’s Cahilty Lodge along with husband, Al Raine, former head coach and program director of the national team. “I trained a lot with the guys, so I always had somebody around who was skiing better than I was, who was training harder, who I would have a hard time catching up to.”

Based on her success, the International Ski Federation awarded a 1968 World Cup race to her home hill, Red Mountain, in Rossland, British Columbia. It was the first World Cup held in Canada.

Greene retired after the 1968 season, at age 24. Al Raine took over as head coach. The program moved out of Nelson in 1969 when Raine and CASA decided the skiers needed more time on snow and less in classrooms.

But the groundwork had been laid, and the Nelson camp launched an intergenerational success story. First, Betsy Clifford became the 1970 FIS World Slalom Champion, and Kathy Kreiner the 1976 GS Olympic champion. Then Currie Chapman coached the Canadian women when Gerry Sorensen and Laurie Graham took gold and bronze in downhill at the 1982 World Championships, and Scott Henderson coached the men’s team that gave birth to the Crazy Canucks, including Steve Podborski’s World Cup downhill title in 1982 and, eventually, Ken Read’s on-snow success, followed by his longtime stewardship of Alpine Canada.

Freelancer John Korobanik is former managing editor of the St. Albert Gazette, in St. Albert, Alberta.

The Original Team

Head coach Dave Jacobs

Manager Peter Webster

MEN

Gerry Rinaldi

Currie Chapman

Peter Duncan

Rod Hebron

Scott Henderson

Wayne Henderson

Bert Irwin

Jacques Roux

Dan Irwin

John Ritchie

Keith Shepherd

Gary Battistella

Bob Swan

Michel Lehmann

Bob Laverdure

WOMEN

Nancy Greene

Andrée Crepeau

Karen Dokka

Judi Leinweber

Emily Ringheim

Stephanie Townsend

Barbie Walker

Heather Quipp

Garrie Matheson

Jill Fish

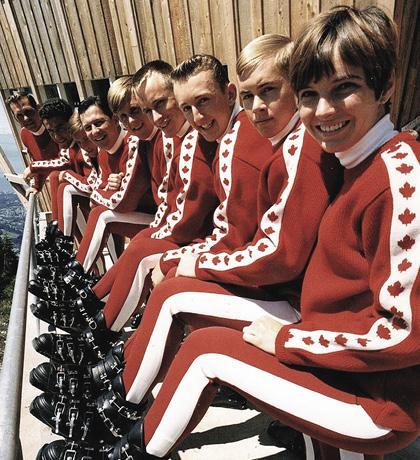

Photo top of page: Volkswagen contributed buses painted in national team colors and members all had a Canadian uniform. “We had never had everyone in the same uniform before,” says Jacobs. “Everyone had a sense of purpose. This was Canada’s national ski team. It gave everyone tremendous incentive.”