A veteran journalist on the world alpine racing circuit recalls moments of high drama—and humor—from the Winter Games.

STORY BY PATRICK LANG

INNSBRUCK 1976

FRANZ KLAMMER’S RECKLESS

GOLD-MEDAL RUN

Franz Klammer produced one of the most thrilling moments in alpine racing history with his reckless gold-medal run on the treacherous Patscherkofel downhill course at Innsbruck, Austria in February 1976. It was a huge achievement, as there was so much pressure on him prior to that Olympic race. The Austrian had become a hero in his country after having won a dozen downhill races in previous seasons. His fans adored his down-to-earth personality and his aggressive style.

Klammer felt he “had” to win the Olympic downhill for the honor of his ski-crazy country and the estimated 60,000 spectators who gathered along the race course to watch the competition. The streets across the nation were empty and factory workers received a special break, so they could watch the event on TV with millions of their compatriots.

Everyone got nervous after defending Olympic champion Bernhard Russi from Switzerland set the best time after a nearly flawless run. The course was rougher when a nervous Klammer pushed himself out of the starting hut. The screams of thousands of spectators must have been heard for miles. The blow-by-blow delivered over the PA system didn’t help their nerves—Klammer was behind the leaders at the intermediate times. Even his coaches were tense. “He is out, he can’t make it…” shouted triple Olympic champion Toni Sailer, alpine director of the Austrian team, after seeing Franz fly high into the air off the Ochsenschlag jump in the upper part of the run.

Everyone got nervous after defending Olympic champion Bernhard Russi from Switzerland set the best time after a nearly flawless run. The course was rougher when a nervous Klammer pushed himself out of the starting hut. The screams of thousands of spectators must have been heard for miles. The blow-by-blow delivered over the PA system didn’t help their nerves—Klammer was behind the leaders at the intermediate times. Even his coaches were tense. “He is out, he can’t make it…” shouted triple Olympic champion Toni Sailer, alpine director of the Austrian team, after seeing Franz fly high into the air off the Ochsenschlag jump in the upper part of the run.

Yet Franz fought hard to stay on line, his arms wheeling in the air while approaching the last turns. He was two-tenths of a second behind Russi. He nearly crashed again on one of the last jumps yet recovered to cross the finish line with the winning time, only a few tenths of a second ahead of his Swiss rival and friend. The crowd went nuts as the announcers in ABC’s commentator booth—Frank Gifford, Bob Beattie and their special host Jackie Stewart, the former Formula One world car-racing champion—told the world the results. “I can’t believe it, he has been amazing!” Stewart said.

Only a few months later, Franz told me how he managed to clinch that title after his fantastic run. “When I started, the course was basically ruined and I knew I had only a small chance to win,” he said. “So I decided to take even more risks than I had planned, especially in the Ochsenschlag section.

“I had seen in training that a few skiers, including Ken Read of Canada, had tested a straighter yet very risky line there. As I approached it, I made a last-second decision to go for it instead of following my usual rounder line. I made a huge jump and thought I would crash, yet I managed to survive and land on my skis. I was not sure how much time I gained or lost, yet it gave me so much determination that I kept risking everything until the last meter.

“I was amused later to discover that I was the only skier who dared to take that line. The other favorites were not as gutsy or crazy. That’s how I won that day.”

Photo caption: The race course was rough and the pressure was on when Klammer pushed out of the starting hut in the downhill. “I knew I only had a small chance to win,” he told the author. “So I decided to take even more risks.”

LAKE PLACID 1980

MOSER-PROELL WINS THE RACE… AND WINS REDEMPTION

Annemarie Moser-Proell dominated her time as no other skier before and after her. The Austrian set an impressive record of 62 victories and 115 podium finishes on the World Cup tour in only 175 competitions. Her last victory—in the Olympic downhill at Lake Placid in 1980—was particularly emotional and a great story, too.

To fully understand Annemarie’s crowning achievement, it’s important to look back at the 1972 Olympics at Sapporo, Japan. She was the skier to beat after her great season start, marked by five victories and four podiums finishes in all three classic specialties: downhill, slalom and giant slalom.

Yet the 18-year-old turned out to be the victim of the political storm that eliminated her teammate Karl Schranz, unfairly disqualified by the IOC at the beginning of the Games for having apparently earned endorsement money as a ski racer.

Schranz didn’t want to leave Japan alone and he put pressure on the entire team to fly back home with him. There were some hot meetings within the Austrian squad, but the other racers didn’t want to miss their chance for an Olympic medal just a few hours before the start of the show.

One of his strongest opponents was the very determined Annemarie Proell. She fought for her rights, yet lost focus and energy during the intense political battle.

After Schranz flew back to Vienna, where he was welcomed by a huge crowd on the main square, “La Proell” did her best to recoup, yet could not achieve her potential on race days. She finished second in downhill and giant slalom behind the unknown Swiss teenager Marie-Therese Nadig, who had never reached any major podium before the 1972 Olympics.

As a consolation prize, Proell won the FIS gold medal for her success in the three-event combined, yet she apparently threw the medal away after receiving it.

Four years later, she missed the 1976 Games at Innsbruck; she had retired from racing the previous year to get married and take care of her dad, who was seriously ill. After his death, she staged a successful comeback. After clinching her sixth crystal globe for the overall World Cup title in 1979, Annemarie was aiming for the elusive Olympic gold medal in 1980 that she had missed eight years before.

Yet this time, she was the hunter: Nadig had dominated the previous downhill races, winning six out of seven, as well as a giant slalom. Moser-Proell had won three events, including a downhill, yet she had not been charging as hard as usual. But she still appeared confident heading into the Games. “I’m fully ready for Lake Placid; I have enough confidence for the big day,” she told me in January after her win at Pfronten in western Bavaria.

At Lake Placid she managed to stay quiet, resolute and ready for the last assault. On race day, she stayed laser-focused as she made her way down the course, despite strong gusts of wind that disturbed some of her main rivals, including Nadig. The Swiss favorite came in third this time, behind Moser-Proell and silver medalist Hanni Wenzel, who took gold in slalom and GS. Eight years after Sapporo, “La Proell” had enjoyed a superb revenge.

“I’m extremely happy. This success means a lot to me after all those years,” she told reporters at the post-race press conference that I was running in the modest base lodge of the resort. “Even though I had nothing to prove here, it’s a special victory after that nightmare in Japan.” The Austrian was obviously relieved to have blown away the dark clouds of Sapporo that had haunted her.

Having followed her career since her first victory in 1970, it was electrifying to hug her after the press conference—a record-setting athlete who had become a good friend.

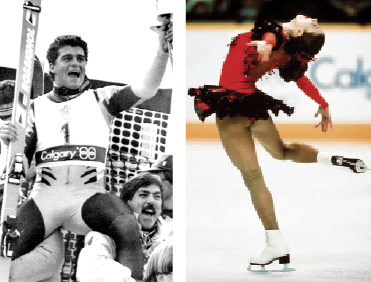

CALGARY 1988

ALBERTO TOMBA, WINNING AND WATCHING WITT

The 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary were particularly intense, with ten alpine competitions held over two weeks. The preceding ski season had been terrific, too, as big crowds closely followed Italy’s unpredictable phenomenon Alberto Tomba, who was dominating the World Cup that season with six victories and a second place standing in the technical events.

In an interview before the Games, La Bomba told the press that his dad, Franco, might buy him a Ferrari if he clinched two gold medals in Canada—a mission he accomplished by winning the slalom and the GS. After his victories, Alberto told me he’d be pleased to watch East Germany’s attractive superstar Katarina Witt competing at the ice arena in Calgary. I spoke about it with ABC studio producer Draggan Mihailovich, a Tomba fan, who organized the journey.

An ABC van brought us from the medal plaza to the Saddledome arena. The Italian skier, closely followed by a crew from a U.S. network, was proudly wearing his two Olympic gold medals around his neck. Thanks to special accreditations, we were standing right at the rink when Witt started to perform.

We had briefly seen Witt during our walk under the crowded stands, as she was exercising with her trainer, Jutta Mueller. As we approached her, Mueller, who recognized Tomba and might have read about his wish to meet her protégé, pushed Katarina into another room, so she wouldn’t be distracted by the handsome Italian playboy.

We enjoyed watching Katarina claim her second Olympic title after a brilliant show. But the skating star didn’t meet Alberto afterwards. They met later that year in Italy during an exhibition—and then again four years later at Les Menuires, the site of the slalom race for the 1992 Albertville Games.

Once more, it was Draggan, working then for CBS, who set up the encounter in a nice restaurant in the French resort. During the evening, Witt expressed her desire to ski once with Alberto, who had just collected his third Olympic title in giant slalom at Val d’Isère. “No problem, let’s meet tomorrow afternoon,” he said.

The next day, Katarina showed up on time with her gear, which Alberto’s personal bodyguard carried up to the hill. Nearly two hours later, they came back smiling. Witt was exhausted but happy about her exclusive ski lesson. “He was adorable. He showed me plenty of tricks and we had so much fun,” she told me afterwards as we sat down to enjoy hot chocolate and cakes.

The next day, Tomba finished a strong second in a slalom dominated by Norway’s Finn Jagge. Two years later, both Tomba and Witt competed again at Lillehammer. This time, Alberto could not attend her performance, but Gen. Norman Schwarzkopf was sitting next to me.

Photo caption: Italian superstar Alberto Tomba won gold in slalom and GS at Calgary, then cheered from the side of the rink as Katarina Witt of East Germany claimed her second Olympic figure-skating title. Four years later, they met for dinner and a private ski lesson. “He was adorable,” said Witt of her time with La Bomba.

ALBERTVILLE 1992

LITTLE-KNOWN PATRICK ORTLIEB SHOCKS THE SKI WORLD

The steep and sinuous La Face course at Val d’Isère, France, which was built in the late 1980s by Switzerland’s Bernhard Russi, the 1972 men’s downhill Olympic champion, launched an unexpected revolution in the sport.

Russi was selected to design the course by Jean-Claude Killy, co-president of the 1992 Olympic organizing committee, who used to ski on that part of the Bellevarde slope as a kid. Russi traced a new type of downhill that required great technical skills from athletes and a high level of performance from their skis. In fact, the course contributed to new technology in ski construction, ultimately leading to the parabolic “shaped” skis now used by most recreational skiers.

The older generation of established alpine speed specialists from that time—led by Swiss racers Daniel Mahrer, William Besse and 1991 downhill FIS world champion Franz Heinzer—had great difficulties in negotiating La Face with their traditional style, which was to enter the turns at full speed and throw the skis sideways to change direction.

The new downhill skis produced ad hoc for the Albertville course were shorter and narrower at the middle. They also required more feeling from the racers, who needed to steer them continuously from the entrance to the exit of each turn. It turned out that powerful skiers could exit the turns with amazing acceleration, a situation that caused some spectacular crashes.

Interestingly, none of the well-known “technicians” on the tour, like multiple overall World Cup champion Marc Girardelli or local favorite Franck Piccard, the 1988 Super G Olympic champion, clocked the fastest downhill time on race day. That honor went to a little-known Austrian from Lech, Patrick Ortlieb, who had never won a major event.

Wearing bib 1 and with nothing to lose, as he didn’t belong to the circle of favorites, he achieved an aggressive yet controlled run and set a time that nobody could beat. Many of the top guns failed to control their line in the tricky parts of the course.

Patrick Ortlieb’s win was the first surprise of the men’s Olympics events at Val d’Isère, yet he confirmed his success in the following seasons with significant triumphs on the World Cup tour, including winning the legendary Hahnenkamm race at Kitzbühel.

Another surprise was revealed later when my father, World Cup founder Serge Lang, intrigued by Patrick’s last name, discovered that he was a double national: Austrian, as he was born in that country from an Austrian mother, but also French through his dad, a cook from Alsace, who had emigrated to Lech to work, raise a family and run the Montana Hotel there.

“Ortlieb is a well-known name in Alsace; I think I know some of his relatives,” explained Lang, who was also born in Alsace in 1920. Patrick Ortlieb admitted afterwards that he had a French passport lying around somewhere at home, yet he was happy to race for Austria.

Ortlieb’s daughter, a tall racer and 17-year-old beauty named Nina, is now a member of the Austrian C squad after achieving some promising international results. She may soon compete on the World Cup tour. “Is she also French?” I asked him at the 2013 World Cup season start at Soelden. “Possibly yes,” he answered with a grin.

Photo caption: Ortlieb takes flight over the men’s downhill course on his way to winning gold at Albertville. He was able to hold his line on a difficult course, while established speed specialists struggled.

NAGANO 1998

AFTER A SPECTACULAR CRASH,

HERMINATOR MEETS TERMINATOR

Some of ski racing’s greatest characters have attracted even more attention from the media and the crowds, thanks to nicknames invented by fans, friends or reporters. The best example is Austria’s Hermann Maier, one of the greatest personalities in alpine ski racing. He became famous in 1998 after clinching two Olympic gold medals—in Super G and GS—at Nagano despite a horrific crash in downhill. After that, he was known as The Herminator.

His formidable appearance, his determination on the slopes, and his numerous victories in the weeks prior to his trip to Japan had led reporters to use rougher nicknames, like The Beast, which Maier didn’t like at all. One of them had also briefly mentioned The Herminator, a combination of his first name and the invincible ‘Terminator” movie character, played by another Austrian legend, Arnold Schwarzenegger.

The nickname became particularly apt after he survived his spectacular flight, several meters above the slope, and the post-landing cartwheels in soft snow. Two days after that frightening accident, he was facing the press to confirm his intention to race the following day in Super G. “It was quite a flight—for sure not as comfortable as our journey over here with Lufthansa,” he said with a grin. In a quick one-camera interview I made with him later on, he added, “I’ll be back!”

During one of our early morning production meetings at the CBS office at Hakuba, I discussed Hermann’s chance to excel in the Super G with play-by-play announcer Tim Ryan. “If anybody could do it, it’s for sure Hermann,” I explained with great optimism. I also told Ryan about that funny nickname and Maier’s comment. “That’s a fun story. We should do a feature on it with Arnold,” he said. “I think he is skiing right now at Sun Valley and I know his ski instructor. I’ll call him.”

Ryan didn’t need much time to get hold of Schwarzenegger’s Austrian-born ski instructor, Adi Erber, and to organize a crew to do an interview with the movie star. Tim also talked directly to “Arnie,” who asked him for Maier’s phone number.

I gave him the local phone number of Austria’s media coordinator, who did receive a call from Idaho after Hermann’s amazing comeback in Super G. Schwarzenegger was so impressed by Hermann’s triumph and his funny nickname that he wanted to speak to him. During the call, he also invited Maier to visit him next spring in Los Angeles.

They also had a great time in California, so it was no surprise when Arnold came the following year to Beaver Creek to encourage his friend, who clinched two more gold medals at the 1999 Ski World Championships. Apparently they also threw quite a party at Arnie’s suite at the Hyatt Hotel to celebrate the wins.

Photo caption: Hermann Maier’s nickname, the Herminator, was inspired at the 1998 Games by the movie character played by Arnold Schwarzenegger. The two became friends. Above: Maier on the GS course in Nagano. Right: Schwarzenegger and Maier at the FIS Alpine World Championships in Schladming in February 2013. Austria in February 2013.

Patrick Lang, the son of World Cup founder Serge Lang, has covered 11 Winter Olympics since 1972 and has written about ski racing for dozens of media outlets. His company BioramaSports.com produces the Ski World Cup Guide and provides TV stations with reports from the World Cup circuit. He is a member of the Skiing History magazine editorial board.

History magazine editorial board.

This article first appeared in the January/February 2014 issue of Skiing History magazine.