Sven Coomer recalls the design process leading to Nordica’s groundbreaking boots.

As told to Seth Masia

In 1962, I went to Chamonix to watch the FIS World Championships and got to train with the French team. I also met Hans Heierling, who was meeting with Trappeur to license their Elite boot, in which the French team was having great success. Nordica took a license, too. I wasted no time getting to Davos to see Heierling’s manufacturing operation. I got a job on the trail crew. Every afternoon for two weeks, after avalanche control and snow maintenance, I visited the boot factory, watching every step of the process while they made my first pair of custom leather double-lace boots.

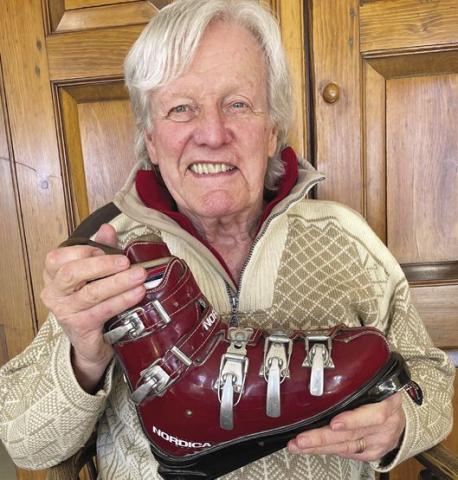

Photo above: Sven today, with the leather Sapporo of 1969. It was the first boot with both a high back and high tongue. Kathy Richland photo.

Heierling licensed the Le

Trappeur Elite design, as did

Nordica. The design won medals

at the 1964 and 1968 Olympics.

I first saw plastic boots in 1965, when I skied with Vail Ski School Director Morrie Shepard, and he offered me the job as his assistant. Morrie was Bob Lange’s ski instructor, and he was skiing in Lange’s double-lace, pre-production boot (Morrie soon went to work full time for Lange). Instead of working in Vail, I accepted the ski school director’s job at the PSIA

coach Dave Jacobs told Bob

Lange to raise the heel and lock

the hinge. The changes didn't

make the boot fit better.

experimental ski school in Solitude, Utah, which sounded much more interesting in the first years of the PSIA [Professional Ski Instructors Association]. After a year at Solitude, I moved on to run ski schools at Mt. Rose and Slide Mountain near Lake Tahoe. In the spring of 1967, Doug Pfeiffer, editor of Skiing magazine, invited me to Mammoth in April and May for the first magazine ski tests. Over six weeks I found that testing equipment, analyzing and problem solving were my true calling. Doug then invited me to New York each summer to write up our ski test reports and compose technical articles on equipment and the emerging techniques of the time.

During the tests in 1967, ‘68 and ‘69, Junior Bounous came to Mammoth to test Rosemount fiberglass boots and asked me to try them. They were very comfortable, with the side-hinge entry-exit door and a collection of fitting pillows to insert in several pockets to adjust the comfort and support. With the mechanical hinging action and very rigid sole, it was a significant contrast to my Nordica leather race boots. When the Canadian team trained at Mammoth, Rod “Yogi” Hebron lent me his Lange plastic race boots. They made my feet numb, as if with Novocain. I couldn’t feel the skis. By comparing the plastics directly to my leather boots, one on each foot, I really noticed that the plastic had the effect of isolating the delicate sensitivity and proprioception and balance feeling of the feet for the skis and snow. That is, the “feeling of leather” was absent.

Leather boots, when well fitted, were stiff and sometimes bruising for a week or two, then felt great. They were good for two weeks of hard skiing and then went soft. We tried reinforcing the leather with layers of fiberglass, with disappointing results. Every brand in the boot business was convinced that plastic would be the final cure for the woes of leather boots. But the first generation of plastic boots, and especially the racing Langes, never grew comfortable. It looked like plastic promised only more durability than leather, and maybe drier feet.

During testing in the spring of 1968, I met Norm McLeod from Beconta, the importer of Nordica boots, Look bindings and Völkl skis. Beconta had kindly supplied me with Nordica boots while I was directing ski schools, and I supplied constructive feedback. We rode Mammoth’s Lift 3 and Norm asked what I thought about plastic boots. “They are interesting,” I told him. “Their impressive durability and shell stability marks them as inevitable. It’s obviously the future, but they still have a long way to go. They are unpredictable. There’s perhaps too much support, and I can’t feel or ski with my feet. They force me to emphasize with my knees, using knee-hooking to start turns. And they hurt!”

We talked for hours about ski boots, and he offered me a job. I joined the company at their San Francisco warehouse early in 1969.

Nordica was playing catch-up to Lange and Rosemount. Lange made a big splash at the 1966 World Championships in Portillo, on the new World Cup circuit in 1967 and at the 1968 Grenoble Olympics. Nordica needed a response. They already had injection-molding machines for the outsoles, but Nordica’s designers were leather-boot artisans and didn’t know how to engineer plastic boots to be truly functional. In 1968 they made a big investment in molds and shot a line of “Astral” thermoplastic shells for introduction in ’69, but these were too narrow and worked no better than existing plastic boots.

I settled in at Beconta with a plan to perfect their leather race boot, then find a way to duplicate that fit and performance in plastic. I fed design ideas to Norm, who airmailed them to Nordica in Montebelluna, Italy. The summary that sealed my relationship with Nordica was about developing integrated high-back boots. Norm told me they were very excited about that and wanted to meet me. Nordica asked me to move to Italy and work in the factory.

Their team of brilliant artisans, led by Piero Martin Iego and Otto Heinz Izzo, made dozens of different custom leather boots and we tried them out with the U.S. and Italian ski teams. Our key discovery was that the high-back should be countered by an equally high tongue, so that the tibia was “centered” with the ankle at its optimum-strength angle.

With racer feedback, I compiled a list of 173 functional design criteria. Then we combined all these ideas into the Sapporo leather slalom boot (see photo, top of page). We got it to racers for the 1969 model year, and we had a number of top slalom skiers in it while everyone else was in Langes. A couple of years later, Fernando Francisco Ochoa won the 1972 Olympic slalom in the Sapporo boot.

the features of the leather Sapporo. The

one-piece plastic shell was replaced by

the two-piece Astral Slalom. Coomer

collection.

Long before that, we pushed ahead to translate the design into plastic. We created a beautifully handcrafted leather inner boot and shaped a shell mold to cradle it accurately. The first result, the Olympic, was a one-piece design (shell and cuff molded as a single unit) based on the final version of Ochoa’s boot. It gave racers tremendous edging power and embodied criteria still used today in all top race boots.

But in 1971–72, Henke had trouble with their plastic boots. The weak plastic cuff straps broke and the warranty costs put Henke out of business. The single mold for the Olympic was difficult to inject and we worried about weakening the cuff straps with voids in the plastic. So the boot was retired prematurely.

boot." Coomer collection.

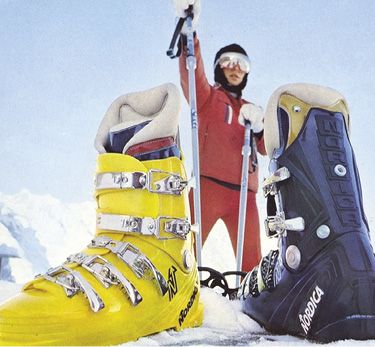

We reworked the shell shapes into a two-piece design, where the separate cuff was a much easier item to injection-mold. That hinged-cuff design reached the market in 1971 as the second-generation Astral series. The real innovation was subtle. Where every other high-performance boot on the market had adopted a high-back “spoiler,” the Astral had a spoiler and a high tongue—higher than the spoiler, in fact. The following year we offered the locked-hinge Slalom model. In North America, it was bright yellow and thus became the “banana boot.” It made all the other race boots on the market look obsolete and cemented Nordica’s worldwide market share at 30 percent.

Sven Coomer will be inducted into the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame, Class of 2022, in the spring of 2023.