Alaskan Native forest ranger was the Renaissance man of ski resort development.

Among the characters who pioneered skiing in New Mexico—and there were plenty—one of the most colorful was a powerful, laughing Aleut Indian from Alaska’s Chugach Mountains: Pete Totemoff.

of Fame in 2004. "An expert eye for

women and good food and spirits."

Grant Therkildsen, courtesy Jay

Blackwood

Totemoff was born in 1918, in the fishing village of Tatitlek at the mouth of Valdez Bay. Like most of the local population, he bore a family name of Russian origin, thanks to the Orthodox missionaries who arrived there around 1750 and converted the entire village. The family soon moved to Cordova, about 80 miles down the coast, population then about 950.

(photo top of page: Totemoff leads the way for Taos instructors. Courtesy Jay Blackwood)

“We were out in the boonies, about five miles from town,” Totemoff told me. The public school was housed in a naval radio station. “I had to ski to school, two miles a day,” he added. “That’s where I learned to ski.”

The Coast Mountains offered plenty of powdery adventure, rising more than 2,500 feet within a couple of miles of home. The snow fell yards deep, about 350 inches each winter, and it was the kind of coastal snow that rewards powerful but smoothly balanced technique. “We’d climb all day for one run,” Totemoff said decades later. “Back and forth, back and forth, just for one stinking run. I used to ski on skis made by Northland Ski Company. They gave you a little book with all the turns and how to do them.”

Out of school at 16, Totemoff went to sea, working trawlers in Prince William Sound and running trap lines in the winter, on skis. It was a popular sport: in a roadless country, people traveled by bush plane, sea and dogsled, and made short trips on skis. Cordova had a ski club, and Totemoff learned about slalom racing. By 1939, he was strong enough to win both the jumping and downhill competitions, for the skimeister crown, at the annual Anchorage Fur Rendezvous, against competition from eight ski clubs across Alaska. Ted Coomera, a ski instructor from Timberline Lodge in Oregon, writing in the American Ski Annual, described Totemoff as “Alaska’s best skier.”

courtesy Jay Blackwood.

But his health wasn’t good. Tuberculosis kept him out of the army in 1941. As Totemoff told it, “In 1943 I came from Alaska to New Mexico for my health because of bad lungs. I spent two years in the hospital in Albuquerque. I’m not cured, but nobody ever knew I only had a lung and a half.”

At the close of World War II, Totemoff came out of the hospital healthy enough to work in a local restaurant. In October 1945, Bob Nordhaus, of the Albuquerque Ski Club, hired him to teach skiing, run the restaurant and operate the rope tow at the club's ski area, La Madera (now Sandia Peak). In later years, Totemoff claimed that no one else could keep the rope tow running. The following autumn, he helped install the new Constam T-bar. “I knew how to ski and I knew how to make a long splice,” he said. “Being someone from the sea, I knew all of the knots and the splices. Nobody else knew how to splice.”

In 1947 Totemoff was hired by the U.S. Forest Service as one of its first snow rangers. His job was to see that new ski resorts on Forest Service land were planned and built in a way that worked for the public. He very naturally became a facilitator, counseling both his Forest Service supervisors and ski-developer friends on how to collaborate, plan and construct new trail systems. Totemoff became instrumental in the development of Sierra Blanca (now Ski Apache) near Ruidoso; Santa Fe Ski Basin; Sipapu; and, most memorably, Taos Ski Valley. He helped plan Brighton in Utah and Arapahoe Basin in Colorado. And he spent much of each summer as a Forest Service fire boss, flying to sites throughout the West. In 1984 he told SKI magazine’s Peter Miller, “I’m proud that no one was ever killed on a fire when I was boss.”

“When I started working for the Forest Service, we made every effort to create an industry of some kind to help people in depressed areas,” Totemoff told me. “In a way, we really created an industry that is one of the biggest in New Mexico. We started a business that really helped the communities when they didn’t have any business at all. Winters were dead.”

He was one of the few Indigenous people involved in the ski industry and felt he had to prove himself to the wider skiing community. “It’s a different situation with me being an Indian,” Totemoff said. “You have to overcome a lot of prejudice. You better show them you can do things just as well as they can and probably better. That’s the way it’s always been. I heard, ‘You don’t look like a skier.’ What’s a skier supposed to look like?”

The fact is that Totemoff had self-taught engineering skills and could out-ski most mortals. He quickly gained the respect of the people he worked with in the Forest Service and at the resorts. He met and became friends with an incredible number of people in the private sector of the ski business. One of them was Taos founder Ernie Blake, who once said, “Taos Ski Valley would not exist were it not for Pete Totemoff. I don’t think we ever paid him a penny, nor could we have afforded his services.”

In 1953, Blake was running Santa Fe Ski Basin. As Totemoff recalled, “Ernie and I got along pretty good up there in Santa Fe Ski Basin. There wasn’t a whole lot of business back then, and we got to skiing together and playing hockey. Ernie made a little ice rink in the back. We did it all; if he needed help fixing the lifts, I’d help him fix the lifts, groom the slopes. Ernie and I did a lot of clearing up in Santa Fe Basin by ourselves. The part where the lift used to be was a rock garden. We spent one summer just shooting [blowing up] rocks. Ernie liked that; he liked to play with powder. Then we had the leak in the propane system, and the lift shack went skyrocketing.”

trades at Madera, now Scandia Peak.

Courtesy Jay Blackwood.

Blake was also operating a small ski area, Red Mountain, in Glenwood Springs, Colorado. He had his own plane, a Cessna 170, and commuted between the two enterprises. To make the flight more interesting he would detour to the east and to the west, scouting for potential ski terrain. Sometimes Totemoff rode along. He recalled, “That flight . . . when we went over Twining, it was one of the worst flights I’d ever been on, and I’ve flown a lot of miles. I started flying way back in the 1930s with bush pilots and air attack (fire bomber) officers in the Forest Service. Ernie was the most nervous pilot I’ve ever been with. It’s a good thing he got rid of that plane or he would have crashed it.”

Blake and Totemoff both liked what they saw of Twining, an old copper-mining camp abandoned since 1895. In May 1954 they went to explore it. They climbed up, carrying their skis, until the snow became too deep and then put on their skins and continued on via Bull of the Woods Trail to Frasier Peak. They skied down the west face of the mountain and the mine slide through three and a half feet of fresh powder, which was light in the morning but very heavy later in the day. They agreed the skiing was great and that this was a place worth investigating.

Totemoff refused to partner with Blake on Taos, the new ski area, but on behalf of the Forest Service he pitched in to help plan and cut trails, and build lifts. He even taught skiing (he got certified in 1958), ran patrol sleds and avalanche routes, all without pay from Taos, while drawing his Forest Service salary. In 1974, as a Forest Service insider, he helped facilitate the acquisition of a used single chairlift (reputedly the original Dollar Mountain chair from Sun Valley) by the Sheridan Ski Club in Cordova, Alaska, for installation on Mt. Eyak. He also contributed to the New Mexico social scene, especially in Taos—Totemoff was a popular raconteur and ladies’ man. In 1978, Sports Illustrated named him one of the top-10 powder skiers in the country.

Totemoff retired from the Forest Service in 1981 and began spending summers in Cordova. He ran a bar, now called Totemoff’s, at Santa Fe Ski Basin. He rekindled his passion for sailing and while skippering his sloop on Elephant Butte Lake, near White Sands, New Mexico, in July 1990, he suffered a fatal heart attack.

Rick Richards grew up in Taos Ski Valley. The quotes in this article are from his book Ski Pioneers: Ernie Blake, His Friends and the Making of Taos Ski Valley.

Jay Blackwood

Instrumental in the development of Taos Ski Valley, New Mexico, Totemoff enjoys his masterpiece with Taos ski

instructors.

We spent one summer just shooting [blowing up] rocks. Ernie liked that; he liked to play with powder.

Jay Blackwood

Grant Therkildsen | Jay Blackwood Collection

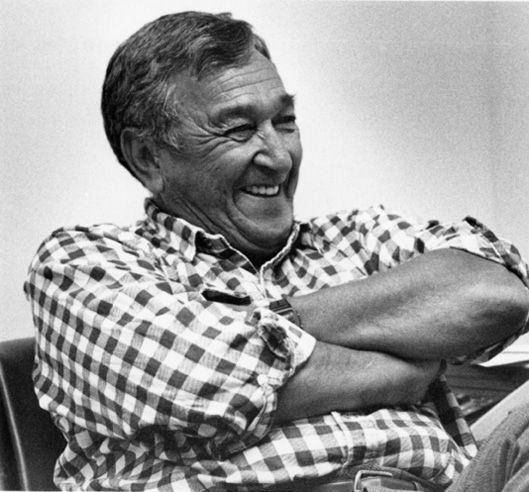

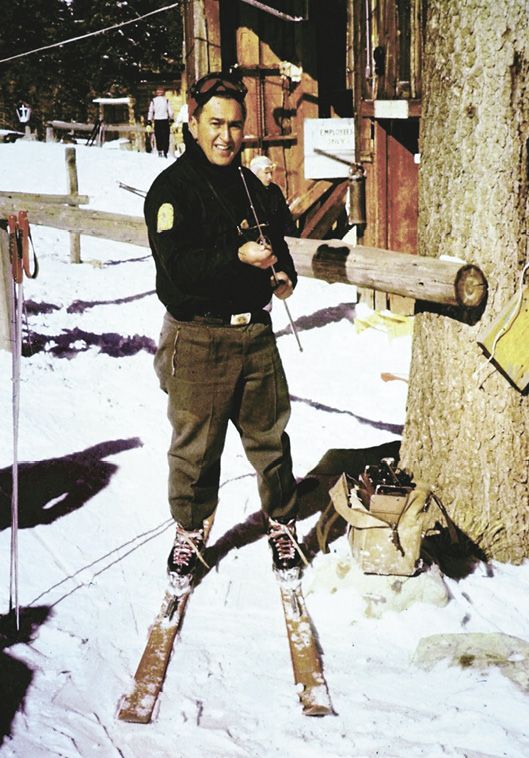

Left: After World War II, Totemoff was a jack of all trades at La Madera ski area, now Sandia Peak. Above: A popular raconteur, Totemoff entered the New Mexico Ski Hall of Fame in 2004. His bio there says he had "an expert eye for women and good food and spirits."