Article Date:

Tuesday, October 6, 2015

After losing his sight, Jean Eymere became an advocate for outdoor sports for blind people…and an icon on the Aspen slopes. By John Sabella

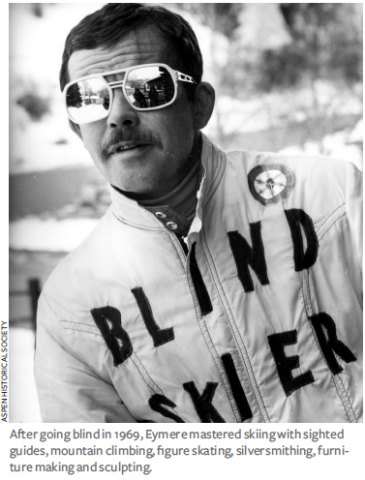

When the glitterati of contemporary Aspen drive north on Mill Street, perhaps en route to this or that Red Mountain mansion, they pass an odd block of marble in the corner of Rio Grande Park, across from Clark’s Market. Few if any take time to study the half-formed figure emerging from the rock, and perhaps fewer still know the name Jean Eymere. What a difference half a century makes.

In 1968, Aspen hosted its first-ever World Cup race. A year later, the U.S. and French national ski teams held a dual meet on Little Nell featuring the head-tohead racing format devised by former U.S. Alpine Team Coach Bob Beattie. At each event, the big star in everybody’s mind was of course Jean-Claude Killy, fresh off his triple Olympic gold medal triumph in Grenoble.

In those years, visiting racers were billeted at local ski lodges and family homes and the issue of who would host Killy became a hot topic among Aspenites. Local lodge owner and Frenchman Jean Eymere was adamant that only he should have the privilege of receiving his countryman at his Coachlight Chalet, and took his case to the City Council where he prevailed.

In those years, visiting racers were billeted at local ski lodges and family homes and the issue of who would host Killy became a hot topic among Aspenites. Local lodge owner and Frenchman Jean Eymere was adamant that only he should have the privilege of receiving his countryman at his Coachlight Chalet, and took his case to the City Council where he prevailed. Even after a disappointing third-place finish in the downhill and a missed podium in the slalom in 1968, in gratitude for the hospitality of a countryman, Killy gave his host a dazzling red ski outfit, stunning in an era of basic black skiwear, and perhaps the first pair of mirrored Vuarnet sunglasses ever to make its way to the Roaring Fork Valley.

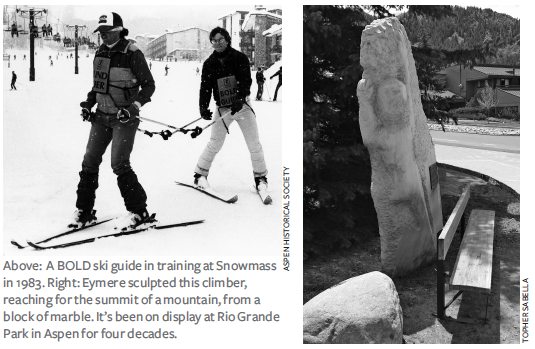

Eymere, a ski instructor at Aspen Highlands at the time, had suffered from diabetes since childhood in the French Alps. His sight began deteriorating at a young age and the impact of clearing a mogul as he descended toward the Highlands base several years after Killy’s visit triggered diabetic retinopathy and instant blindness. Having recently relocated to a small ranch in Carbondale, 30 miles downvalley from Aspen, Eymere struggled to the bottom of the mountain and caught a ride home, where he wallowed in depression until several of his ski instructor buddies packed him in the car with his ski equipment, drove him back up valley and insisted he hit the slopes again. Protesting all the while, Eymere reluctantly gave skiing another go, and the group conceived a system in which a sighted guide following close on the ski tails of the blind man called signals: left, right, left, left, right, stop.

Later, I guided him many times and as long as he had my voice constantly barking reassurance, Eymere skied effortlessly. If I went silent, he immediately skidded to a stop for fear that his “eyes” had deserted him.

Eymere and his guides became a common sight on the slopes of Aspen ski hills, the Frenchman unmistakable in Killy’s spectacular red suit and Vuarnets, wearing a Blind Skier bib on his chest. The concept of a blind outdoor athlete, a skier no less, was revolutionary at the time and sighted skiers swarmed around the Frenchman to marvel at his undertaking.

Eymere reveled in the attention, especially the flattery of admiring females. He accepted every invitation for an après-ski drink and often leaned close to me to inquire in a conspiratorial whisper, “She eez good looking, zees one next to me?” His exploits became the inspiration for the Blind Outdoor Leisure Development (BOLD) program that opened the doors in the United States for the blind to participate in countless activities that had always been denied them.

The transition from treating the blind as shut-ins to appreciating their athletic potential wasn’t entirely smooth. Raised in the Haute Savoie near Chamonix, Eymere had been a skier since early childhood, a racer as a young man and a ski instructor. “You could do it because you already knew how,” critics told Eymere when he tried to promote the notion of blind outdoor recreation. “It would be a different story if you had tried a sport that was entirely new to you.”

Confronted with that challenge, Eymere took up figure skating at the Aspen Ice Rink across the street from the Coachlight and became a competitive skater. Later, using a vaulting pole borrowed from the Aspen High School track team, Eymere and sighted guides climbed the 13,000-foot Mt. Sopris that loomed across the valley from the Frenchman’s Carbondale ranch: Eymere grasped the middle of the pole with a guide at either end. Later, Eymere and his team summited even more formidable Pyramid Peak.

Eymere became a true, homegrown Aspen celebrity, regularly marching with his guide dog and “Blind Skier” bib in the annual Winterskol Parades in January. After the novelty of seeing a blind skier had worn off among the locals, Eymere modified his bib to read “Blind Hunter” and marched with a shotgun over his shoulder.

A silversmith by trade, the sightless Eymere became an enthusiastic craftsman, adorning every door and window in the Coachlight with gingerbread trim he cut with a band saw, relying on the wind from the whirling blade against an exposed forefinger that traced the edge of a pattern. When he ushered me into his workshop to show me the procedure, I stumbled through pitch-black darkness until the blind man realized my predicament and turned on the rarely used overhead light. The sudden illumination revealed what to me appeared to be complete chaos but I quickly discovered that Eymere knew the location of every item in the clutter, relying on a system that depended on touch rather than sight. A moment later while the Frenchman chattered away, I winced as the band saw tore through an inch-thick board with the blade whirring a fraction of an inch from his finger.

Eymere went on to become an accomplished furniture builder, crafting the chairs and tables at the Coachlight as well as the altar chair for his church, before taking up marble sculpture. His friends procured discarded blocks of stone from the abandoned quarry in nearby Marble, Colorado and Eymere set to work wielding a pneumatic chisel and the same air-against-the-fingertip technique he used with power saws. With a sensibility bordering on the baroque and a taste for gingerbread, the blind man’s first effort was a classical representation of a nymph bending forward at the edge of a lake. Roughly the size of a shoebox, the piece was finely detailed; something any sighted sculptor not named Rodin could be proud of.

Encouraged, Eymere dispatched his teamsters to retrieve a massive block of marble, taller than a man, and set out to conceive his masterpiece: a climber clinging to a sheer cliff and reaching for the summit of the mountain. It was a metaphor for the Frenchman’s tireless quest to overcome his own disability. On summer afternoons as I pulled into his driveway, I’d see him standing on a stepladder, blasting away at the rock as a shower of marble dust rained over him. Whenever he recognized the sound of my car, he descended the ladder, turned and stuck out his hand with a hearty, “Hi John, nice to see you,” as I struggled to suppress my laughter. From head to toe, including the surface of the prized Vuarnets, Eymere was plastered with a thick coat of white.

I could clearly see the shape of the climber emerging from the rock and I have no doubt it would have been as finely executed as the nymph if diabetes hadn’t killed Eymere at age 43 in 1979. In tribute to the Frenchman, the City Council of four decades ago placed the statue in Rio Grande Park where it stands today, as contemporary Aspenites pass by bewildered by the misshapen rock and oblivious to the story of its genesis.