The critical role of skis in 130 years of Arctic exploration and adventure.

By Jeff Blumenfeld

In Part I of this two-part article, author Jeff Blumenfeld explains how skis played a critical role in the early Arctic and polar expeditions of Fridtjof Nansen (Greenland, 1888), Robert E. Peary and Frederick Cook (North Pole, 1909), Roald Amundsen and Robert F. Scott (South Pole, 1911 and 1912). In Part II, to be published in the January-February 2018 issue of Skiing History, Blumenfeld will examine the use of skis in modern-day polar expeditions by Paul Schurke, Will Steger and Richard Weber.

Blumenfeld, an ISHA director, runs Blumenfeld and Associates PR and ExpeditionNews.com in Boulder, Colorado. He is the recipient of the 2017 Bob Gillen Memorial Award from the North American Snowsports Journalists Association, was nominated a Fellow of the Royal Geographic Society, and is chair of the Rocky Mountain chapter of The Explorers Club. No stranger to the polar regions, he’s been to Iceland more than 15 times, traveled on business 184 miles north of the Arctic Circle in Greenland, and chaperoned a high-school student trip to the Antarctic Peninsula.

Throughout the modern era of polar exploration, skis have played an invaluable role in propelling explorers forward—sometimes with dogsled teams, sometimes without, and more recently, with kites to glide across the polar regions at speeds averaging 7 mph. Modern-day polar explorers including Eric Larsen, Paul Schurke, Will Steger and Richard Weber all continue to use skis today, taking a page right out of history. Were it not for skis, reaching the North and South poles in the early 1900s might have been delayed until years later.

Throughout the modern era of polar exploration, skis have played an invaluable role in propelling explorers forward—sometimes with dogsled teams, sometimes without, and more recently, with kites to glide across the polar regions at speeds averaging 7 mph. Modern-day polar explorers including Eric Larsen, Paul Schurke, Will Steger and Richard Weber all continue to use skis today, taking a page right out of history. Were it not for skis, reaching the North and South poles in the early 1900s might have been delayed until years later.

“Stars and Stripes Nailed to the North Pole”

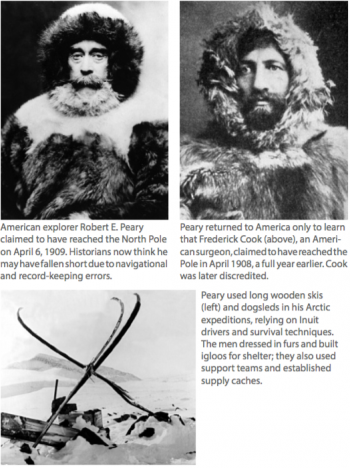

This long-awaited message from American explorer Robert E. Peary (1856–1920) flashed around the globe by cable and telegraph on the afternoon of September 6, 1909. Reaching the North Pole, nicknamed the “Big Nail” in those days, was a three-

This long-awaited message from American explorer Robert E. Peary (1856–1920) flashed around the globe by cable and telegraph on the afternoon of September 6, 1909. Reaching the North Pole, nicknamed the “Big Nail” in those days, was a three-

century struggle that had taken many lives, and was the Edwardian era’s equivalent of the first manned landing on the moon.

But was Peary first to achieve this expeditionary Holy Grail? To this day, historians aren’t absolutely sure whether Peary was first to the North Pole in 1909, although they are convinced both he and Frederick Cook (1865–1940) came close. Of course, Cook’s credibility wasn’t enhanced by his 1923 conviction for mail fraud, followed by seven years in the U.S. federal prison in Leavenworth, Kansas.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t until 1986 that the possibility of reaching the pole without mechanical assistance or resupply was finally confirmed, thanks in part to the use of specially designed skis. That was the year a wiry Minnesotan named Will Steger, a former science teacher then aged 41, launched his 56-day Steger North Pole Expedition, financed by cash and gear from more than 60 companies. The expedition would become the first confirmed, non-mechanized and unsupported dogsled and ski journey to the North Pole, proving it was indeed possible back in the early 1900s to have reached the pole in this manner, regardless of whether Peary or Cook arrived first.

Dogs are the long-haul truckers of polar exploration. For Steger’s 1986 journey, he relied upon three self-sufficient teams of 12 dogs each—specially bred polar huskies weighing about 90 pounds per dog. The teams faced temperatures as low as minus 68 degrees F, raging storms and surging 60-to-100-feet pressure ridges of ice.

To keep up with dogs pulling 1,100-pound supply sleds traveling at speeds of up to four miles per hour, team members used Epoke 900 skis, Berwin Bindings, Swix Alulight ski poles and Swix ski wax, according to North to the Pole by Will Steger with Paul Schurke (Times Books/Random House, 1987). In its basic equipment, this mode of travel was not far removed from the early days of polar exploration.

Norway’s Best Skier Crosses Greenland

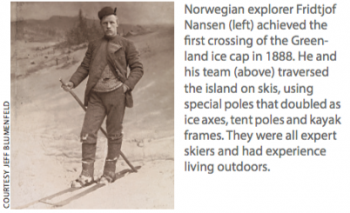

Norwegian Fridtjof Nansen (1861–1930), an accomplished skier, skater and ski jumper, carved his name in polar exploration by achieving the first crossing of the Greenland ice cap in 1888, traversing the island on skis. Nansen was something of a Norwegian George Washington, revered as a statesman and humanitarian as well as an explorer. He rejected the complex organization and heavy manpower of other Arctic ventures, and instead planned his expedition for a small party of six on skis, with supplies man-hauled on lightweight sledges. His team included two Sami people, who were known to be expert snow travelers. All of the men had experience living outdoors and were experienced skiers.

Despite challenges such as treacherous surfaces with many hidden crevasses, violent storms and rain, ascents to 8,900 feet and temperatures dropping to minus 49 degrees F, the 78-day expedition succeeded thanks to the team’s sheer determination and their use of skis. In spring 1889, they returned to a hero’s welcome in Christiania (now Oslo), attracting crowds of between 30,000 to 40,000—one-third of the city’s population.

Nansen later won international fame after reaching a record “farthest north” latitude of 86°14’ during his North Pole expedition in 1895, sadly falling short of the Big Nail by a mere 200 miles.

Nansen’s Greenland expedition would be repeated and completed, again on skis, 67 years later by the 27-year-old Norwegian Bjorn Staib in 1962. It took Staib and his teammate 31 days to cross the almost 500-mile-wide ice cap. “The skis served them well,” according to a story by John Henry Auran in the November 1965 issue of SKI Magazine. He quotes Staib, “There were steep slopes in the west, but we never knew where the crevasses would be. So we zipped across as fast as possible—sometimes I wished we had slalom skis—and hoped that we were safe and wouldn’t break through.”

Writes Auran, “Skis, always essential for Arctic travel, now became indispensable. Crossing ice that sometimes was only the thickness of plate glass, the skis provided the essential distribution of weight which kept the men from breaking through. And they made speed, the other margin of safety, possible.”

In 1964, Staib would attempt to ski to the North Pole but was turned back 14 days from his goal by poor ice and extreme cold. Nonetheless, he had nothing but praise for the use of skis on the expedition. Their simple Norwegian touring skis with hardwood edges performed without difficulty.

Says Staib, “Skiing in the Arctic is not like skiing at home. There’s no real variety, there isn’t even any waxing. There is no wax for snow so cold and, anyway, there is no need for it. There are no hills to climb or descend.”

Scott of the Antarctic

Scott of the Antarctic

Nansen’s techniques of polar travel and his innovations in equipment and clothing influenced a future generation of Arctic and Antarctic explorers, including one whose failure in January 1912 was considered a blow to British national pride on par with the wreck of the Titanic three months later.

British Capt. Robert F. Scott (1868–1912) became a national hero when he set the new “farthest south” record with his expedition to Antarctica aboard the 172-foot RRS Discovery in 1901–1904. Nansen introduced Scott to Norwegian Tryggve Gran, a wealthy expert skier who had been trying to mount his own Antarctic expedition. Scott asked Gran to train his men for a new expedition, an attempt to be first to reach the geographic South Pole, while conducting scientific experiments and collecting data along the way. After all, who better to teach his men? Most Norwegians learned to ski as soon as they could walk. Arriving in Antarctica in early January 1911, Gran was one of the 13 expedition members involved in positioning supply depots needed for the attempt to reach the South Pole later that year.

Scott found skiing “a most pleasurable and delightful exercise” but was not convinced at first that it would be useful when dragging sledges. He would later find that however inexpert their use of skis was, they greatly increased safety over crevassed areas.

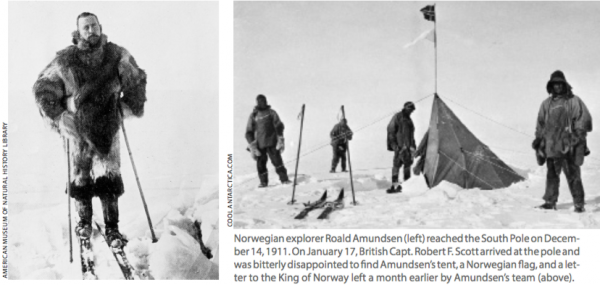

“With today’s hindsight, when thousands of far better-equipped amateurs know how difficult it is to master skiing as an adult, Scott’s belief that his novices could do so as part of an expedition in which their lives might depend on it seems bizarre,” according to South—The Race to the Pole, published by the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London (2000). Scott was bitterly disappointed when he arrived at the bottom of the world on January 17, 1912, only to find a tent, a Norwegian flag, and a letter to the King of Norway left more than a month earlier by the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen (1872–1928), on December 14, 1911.

Amundsen had kicked off his successful journey to the South Pole by traveling to the continent in the 128-foot Fram, a polar vessel built by Nansen. He averaged about 16 miles a day using a combination of dogs, sledges and skis, on a polar journey of 1,600 miles roundtrip. With Amundsen skiing in the lead, his dogsled drivers cried “halt” and told him that the sledgemeters said they were at the Pole. “God be thanked” was his simple reaction.

Over a month later, the deity was again invoked, but under less favorable conditions. After Scott reached the South Pole, man-hauling without the benefit of dogs, he famously wrote in his diary, “Great God! This is an awful place and terrible enough for us to have laboured to it without the reward of priority.”

On their way back from the South Pole, Scott’s expedition perished in a blizzard just 11 miles short of their food and fuel cache. A geologist to the very end, Scott and his men were found with a sledge packed with 35 pounds of rock samples and very few supplies.

On their way back from the South Pole, Scott’s expedition perished in a blizzard just 11 miles short of their food and fuel cache. A geologist to the very end, Scott and his men were found with a sledge packed with 35 pounds of rock samples and very few supplies.

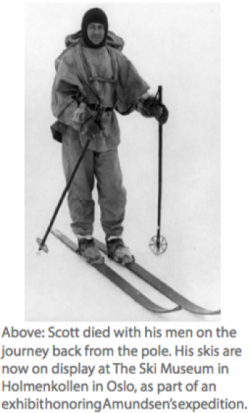

In November 1912, Gran was part of the 11-man search party that found the tent containing the dead bodies of the Scott party. After collecting the party’s personal belongings, the tent was lowered over the bodies of Scott and his two companions and a 12-foot snow cairn was built over it, topped by a cross made from a pair of skis. The bodies remain entombed in the Antarctic to this day.

Gran traveled back to the base at Cape Evans wearing Scott’s skis, reasoning that at least Scott’s skis would complete the journey. Today those skis can be seen in an exhibit at The Ski Museum in Holmenkollen, on the outskirts of Oslo, honoring Amundsen’s historic discovery of the South Pole. Scott would most certainly roll over in his grave at the thought of his skis displayed near those of his polar rival.

L ater polar expeditions would go on to combine skis with kites, with snowshoes, and floating sledges. Sometimes they even attracted the attention of world leaders.

ater polar expeditions would go on to combine skis with kites, with snowshoes, and floating sledges. Sometimes they even attracted the attention of world leaders.