How a young Killington employee in 1963 found a new and better way to attach lift tickets to people. By Karen D. Lorentz

Jennifer Hanley was shocked when she went skiing in Tignes, France in 1987 and was handed a lift ticket and a wicket. “She had no idea the wicket had spread to Europe,” recalls her father Charlie Hanley, who invented the now-ubiquitous wire device in 1963.

Jennifer Hanley was shocked when she went skiing in Tignes, France in 1987 and was handed a lift ticket and a wicket. “She had no idea the wicket had spread to Europe,” recalls her father Charlie Hanley, who invented the now-ubiquitous wire device in 1963.

“For 40 years, the wicket was useful,” he adds. He’s being modest. More than 50 years later—despite the development of new technologies and methods, like RFID cards and plastic zip-ties—wickets are still in use at ski resorts around the world.

In the summer of 1960, Hanley was running Golf-land, his miniature golf course and snack bar in Bomoseen, Vermont. “They could use you up at Killington,” said his Pepsi Cola rep. In need of winter work, Hanley scheduled an interview with Killington founder Preston Leete Smith.

“I was intrigued by the ski-area venture, so I agreed to design and build a kitchen system for the new base lodge,” says Hanley. “Killington couldn’t afford to hire me until after Christmas, so I said I could start in October and be paid retroactively. They jumped at the deal! I got $1.50 an hour.” That winter, he and his wife Jane also ran the resort’s food-service operation.

Recognizing Charlie’s expertise in writing detailed reports, Smith promoted him to “systems analyst,” a position that entailed “trying to solve any problem” that Hanley spotted. To address the theft of rental skis, he installed a Regiscope, “a machine I’d seen in a local supermarket. It took simultaneous pictures of the skier and rental slip and solved the theft problem because a picture is intimidating to a thief. It worked so well that we never had to develop the film.”

A bigger problem: transfer of lift tickets

Having started Killington on a shoestring in 1958, Smith faced a more serious problem with his stapled-on lift tickets. Not only did they leave holes in skiers’ clothing, they were often transferred from one skier to another, denying the area much-needed revenue.

“We noticed that some people were trying to attach tickets using pipe cleaners,” recalls Smith. “I wanted something with more strength yet less bendable, so it wouldn’t break or come off easily.”

Hanley remembers seeing a presentation in Smith’s office by a man wanting to sell “a complicated device. It was a regular keychain with a tiny ring attached at one end and a large coil at the other end.

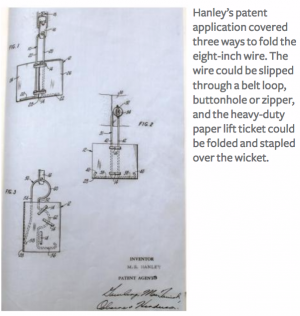

“When he saw me studying it, the salesman said, ‘Oh, I see you, young fellow. You think you can find a way to make it simpler. Well, it can’t be done.’ I’ll never forget that. He was just arrogant enough to get me thinking. We sent him on his way and in five minutes I had the concept in mind. I took an eight-inch piece of wire and bent it in such a way as to allow the wire to be slipped through a zipper talon, belt loop or buttonhole, or around a strap. The heavy-duty paper lift ticket could be folded and stapled over the gizmo’s legs. We called it the gizmo until Jane came up with the name.”

“The U-shape reminded me of the wickets in croquet, so I suggested ticket wicket,” says Jane.

From design to patent

Offered a free trip around the country if he could prove that the wicket would sell, Hanley took his tall blond wife to a national ski operators’ convention, where she demonstrated how the wicket could be attached to clothing without damaging the fabric. As Jane shed various layers, she showed that the wicket would work with parkas, sweaters, stretch pants and, finally, a swimsuit.

Sales were so good that the Hanleys enjoyed the promised trip across ski country in the fall of 1963. “We visited most of the major areas in the United States—there weren’t that many then,” Charlie recalls. “Vail had just opened and I came away with a sense of awe.” Stops in Denver, Seattle, Snoqualmie and Sun Valley are standout memories, as was one visit to an Ohio gravel pit: “Someone had dug out dirt and piled it into a hill and put a lift on it.” Their late-1950s Citroën had a passenger seat that reclined, so one could sleep while the other drove during the three-week journey.

For the 1963–1964 season, Killington sold 750,000 stainless-steel wickets to 62 U.S. ski areas. The next season, they switched to galvanized wire, which cost 40 percent less, and sold to 100 areas. In the third season, they hired a Connecticut firm to handle the growing sales. A fall 1965 ad in Ski Area Management magazine read: “Stopping just one cheater in 1,000 skiers will pay for the cost of Ticket Wickets.” (A lift ticket cost $5-$7 then.)

The Sherburne Corporation was issued U.S. patent 3,241,255 on March 22, 1966 and Canadian patent 742,863 on September 20, 1966. Hanley had assigned the rights to Killington’s parent company because he had developed the wicket while on the area’s payroll. Interestingly, the patent applications anticipated sticky-backed tickets by noting that tickets could be secured to the wicket “with either an adhesive or staples.”

Wickets: Still Hanging around

Sherburne Corporation sued an Ohio firm for patent infringement in 1969 but eventually dropped the suit and sold the patent. “Others were infringing the patent [with different wicket shapes] but bringing lawsuits was costly. Since the patent only lasted for 17 years, it didn’t make sense to pursue the cases,” Smith says.

“The wickets sold for pennies, so it wasn’t worth the time or expense to sue. Ticket wicket wasn’t a money-making business, it was a way to solve problems,” Hanley adds.

Sometime in the 1970s, Killington shifted to using pressure-sensitive adhesive on the back of computer-generated tickets. In 2004–2005, the resort switched to the plastic tie that’s threaded through a coated “tag” ticket and looped to a closure. Although many areas have changed to tie-tag ticketing and others have adopted RFID cards, reports of the wicket’s demise are exaggerated: U.S. companies from coast to coast still manufacture and distribute ticket wickets, including Standard Portable (New York), Southington Tool & Manufacturing (Connecticut), and Amlon Industries and Gold Coast (California).

“Half the lift tickets sold today are secured to a guest via a wire wicket and half with ties,” says Jason Shoats, vice president of sales for Worldwide Ticketcraft. “Smaller areas can’t afford the new methods, and RFID [cards] are more expensive.”

A half-century later, Charlie Hanley’s ticket wicket is still hanging around.

Vermont ski writer Karen Lorentz is author of Okemo: All Come Home, Killington: A Story of Mountains and Men, and The Great Vermont Ski Chase.