Former World Cup superstars and siblings Andreas and Hanni Wenzel have found post-racing success in the business world.

By Edith Thys Morgan

Weg vom Computer raus in den Schnee.” That motto, which urges kids to get away from their computers and out in the snow, is what drives Andreas Wenzel. And it has him driving a lot. In addition to his duties as President of the Liechtenstein Ski Federation, Wenzel is Secretary General of the four-year-old European Ski Federation, an organization of 11 European national ski federations united to grow, promote and improve snowsports in Europe. Wenzel leads the charge on SNOWstar, a series of competitions that combine elements of alpine racing, freestyle and skicross and takes place at partner venues throughout Europe. We’re talking while he drives to Bolzano, Italy, for a symposium on tourism and kids. “It’s not boring,” he says of the constant travel throughout the Alps. “The only thing is the traffic!”

As comfortable as he is on the road and getting things done, Wenzel, half of the brother/sister combo that turned tiny Liechtenstein into a skiing powerhouse in the 1970s and ’80s, much prefers being active in the great outdoors. His connection to nature can be traced to his father, Hubert, a passionate mountaineer and world university champion in the alpine/nordic/jumping combined.

Hubert was among the millions of East Germans who fled west in the early 1950s. He left on bicycle with no money, headed for Munich to study forest engineering. There he met and married Hannelore, a Bavarian shot-put athlete. In 1955, Hubert set out to tour the Alps by bicycle, and after an accident in Switzerland walked 50 kilometers with his bike until he found a shop in Liechtenstein that could fix it. While earning the money for the repairs, he learned that his skills in both engineering and avalanche protection were much in demand in the 62-square-mile country comprised mostly of steep terrain. In 1958, the Wenzels moved to Liechtenstein, with one-year-old Hanni and four-month-old Andreas.

Hubert passed his love of the outdoors to his four children—Hanni, Andreas, Petra and Monica—and instructed them to spend every spare moment being active in the mountains. “We were educated to compete,” Andi explains. “That is not always good from a pedagogical side,” he says with laugh that hints at an intensely competitive household. (Younger sister Petra was 4th in GS in the 1982 Worlds.) The emphasis, however, was always on enjoying the mountains. “As a kid I was out in nature full power,” he recalls. “I was a lousy runner around a track but get me into the mountains and watch out!” The siblings’ ski racing talents grew and in 1974, 17-year-old Hanni, racing for West Germany, won the world championship in slalom. The family was granted citizenship in Liechtenstein and in 1976 Team Liechtenstein (including the three Wenzel siblings, in addition to Paul and Willy Frommelt and Ursula Konzett) integrated for training with the Swiss Ski Team.

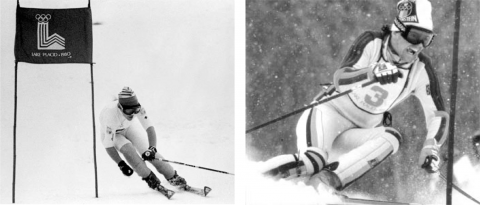

Andreas attended Austria’s famed Stams ski academy, competing in his first Olympics in 1976, at age 17. In those Innsbruck Games, Hanni won Liechtenstein’s first Olympic medal, a bronze in the GS, and two years later Andreas earned his own world title in GS. But it was at the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics where Hanni and Andreas stole the show in their iconic white and yellow suits, producing four medals (and the first gold) for Liechtenstein. Hanni won a gold medal in both slalom and giant slalom, and a silver medal in downhill, while Andreas nabbed the silver in GS, bested only by Ingemar Stenmark and one of his signature second-run comebacks. The siblings crowned that season by each winning the overall World Cup title.

Hanni competed another four years, but along with Ingemar Stenmark was banned from the 1984 Olympics for her semi-professional status. She retired after the 1984 season, with 33 World Cup wins and two overall World Cup titles. Andreas retired in 1988 after his fourth Olympics, with 14 World Cup wins in all disciplines but downhill. Upon retiring, Andreas immediately dove into work, as racing director for Atomic. After four years there he switched to sports marketing, and was instrumental in bringing the first European sponsors (like Warsteiner beer) to North American ski races. Ten years later, he shifted gears again, becoming a tourism consultant. Then, in 2006, he was asked to become president of the Liechtenstein Ski Federation, and found himself back in the ski racing game.

The Liechtenstein Federation includes nine Skiclubs that teach kids until they are 10 years old. After that, the best qualify for the U12, U14 and U16 programs. The federation has 40 nordic, alpine and biathlon athletes and 11 trainers, but as ever, cooperates with other small nations to provide the best possible training framework. For example, Tina Weirather (daughter of Hanni and Austrian downhill great Harti Weirather, and a star on the current World Cup) races for Liechtenstein, but attended Stams and is now fully integrated on the Swiss team.

It is Wenzel’s work with ESF that keeps him on the road, and brings all of his athletic and business experience together with his passion for growing the sport. In Europe as in this country, kids are spending more time in front of screens and social media, and less time outdoors. “In Europe, we have seventy million people living close to the mountains. We want to get them in the sport and keep them in the sport while developing skills. And having fun is most important!” The SNOWstar events in particular—ten qualifying events and a European final—are aimed at doing just that in a safe environment for kids aged 10 to 16.

The events do not involve multiple sets of skis or race suits and are not set on an icy track. Rather, they are on less-harsh “Playground Snow” (a permanent infrastructure at the resorts, similar to a terrain park), studded with built-in features that demand athleticism while keeping the events lower in speed and higher on fun. Wenzel, known by fellow competitors for his intensity as well as his likeability, thinks kids should back off on ski racing’s regimented rigidity. “If you have to use a measuring tape to set GS for kids, something is not right,” he says. Instead, the courses are set in harmony with the natural terrain, teaching kids how to react and move. “Every day, conditions are different. It’s not just about making a fast turn, though that is important. It is about judgment.”

Wenzel reflects on his own upbringing, and on his father’s melding of nature and training in a competitive atmosphere, when he looks at what he hopes the SNOWstar events will help cultivate in kids. “Kids need to learn intuition, which is not something you can learn in a book,” he says. Intuition is what you do when you don’t have time to think, when you come around a corner fast and have to react to whatever is in your path. “More intuition, less thinking,” he explains. “You have to move with fluidity. Those who panic later rather than earlier are going to win the race.”

Wenzel’s drive to create more opportunities for kids outside the traditional ski racing pedigree is personal. “You know, the raw diamonds come not so much from the Gstaad’s and St Moritz’s. They come from tiny villages,” he says. And even, perhaps, tiny countries.