The Forgotten Era of Ski Jumping

Sun Valley opened in December 1936, and the next spring it hosted America’s first international Alpine competition, the combined event that became known as the Harriman Cup. Dartmouth’s Dick Durrance made national headlines by beating the top European racers.

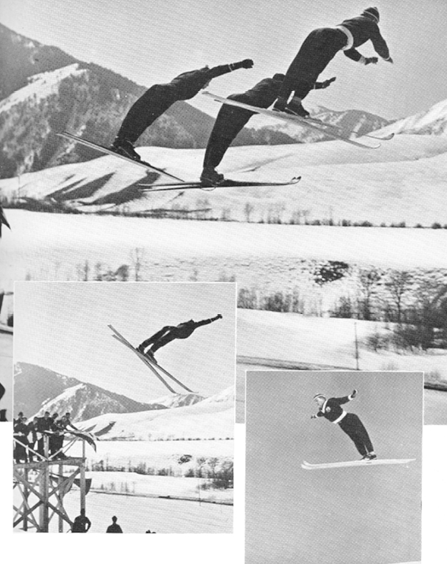

Photo top of page: From left, Olav Ulland, Gustav Raaum, Alf Engen and Kjell Stordalen in formation at Ruud Mountain, 1948. Ulland and Engen were at the end of their jumping careers; Raaum and Stordalen, Norwegian exchange students, were newcomers. National Nordic Museum photo

Alpine skiing was a fledgling sport. For most Americans of the era, ski competition meant jumping. Norwegian immigrants had made ski jumping into a popular spectator sport, with a successful professional circuit. The best-respected racers were Skimeisters—men who could compete in four-way events featuring jumping, cross-country, downhill and slalom. Sun Valley founder Averell Harriman knew that to make Sun Valley the country’s center of skiing, he needed a ski jumping hill.

National Championships. Marriott Library

Two famous Norwegian ski jumpers competed in the first Harriman Cup: Sigmund Ruud (1928 Olympic silver medalist) and Alf Engen (Professional Ski Jumping Champion 1931–1935 and holder of five world professional distance records). Harriman asked Engen (whom he later hired as a sports consultant) and Ruud to locate a ski jumping hill on Sun Valley property. They selected a site between Dollar and Proctor mountains, with an elevation of 6,600 feet and a 600-foot vertical drop. Taking advantage of the hill’s natural slope, they helped design a 40-meter jump, intended for distances of up to 131 feet, For major jumping competitions, an 80- or 90-meter jump would have been necessary, but the 40-meter hill offered “splendid competition for all classes of competitors” and was particularly suited for four-way competitions. Named for Sigmund, Ruud Mountain became the resort’s center for jumping and slalom events and was used for freeskiing. Sun Valley was the country’s only ski area eligible to host FIS-sanctioned four-way competitions.

The term J-bar didn’t yet exist, but Sun Valley had one built in 1936, called a drag lift, to take skiers over level ground from near the Sun Valley Lodge to the Proctor Mountain chair. This was converted into a rudimentary chairlift for Ruud Mountain, without so much as a backrest or a place to rest one’s skis. This gave Sun Valley one of the first lift-serviced slalom courses on the continent.

Ruud Mountain was inaugurated during Christmas 1937 at Sun Valley’s first intercollegiate ski tournament, between Dartmouth (Eastern champions) and the University of Washington (West Coast champions). During a jumping exhibition, Walter Prager (Dartmouth’s coach), Alf Engen and Otto Lang (Washington’s coach) each jumped more than 40 meters, exceeding the hill’s design limit. Prager said the hill offered “one of the finest and toughest slalom courses he had ever seen.” Engen said Sun Valley’s jump “for its size comes nearer to perfection than any yet developed.” And Lang said the jump was “impeccably engineered and groomed... virtually fall-proof… the neatest layout I had ever seen” (The Valley Sun, January 11, 1938) .

lift. Community Library.

In 1938, women were invited to compete in the Harriman Cup for the first time. Grace Carter Lindley from Seattle, a 1936 Olympian, won the women’s Harriman Cup. She said “Ruud Mountain is the perfect slalom hill. Having the tow available for unlimited rides, one can become thoroughly familiar with the contours of the hill, the general layout of the slalom, and most important, one can gauge the conservative speed one can hold without tiring...”

The 1938 Open Jumping Tournament attracted some of the best jumpers in the world, including the famous Ruud brothers from Kongsberg, Norway: Birger (the 1932 and 1936 Olympic gold medalist) and Sigmund. The hill, with its lift, delighted the competitors, “who had been climbing for their skiing all season or jumping off rickety scaffolds on artificial snow” (American Ski Annual, 1938–39).

Before the event kicked off, Engen jumped 50.5 meters. It didn’t count for the competition but stood as the official hill record. Birger Ruud jumped 48 meters to win, and seven jumpers exceeded 40 meters. Norway’s Nils Eie (world intercollegiate champion) placed second “in beautiful form,” Sigurd Ulland (1938 National Ski Jumping Champion) was third, and Alpine ace Dick Durrance finished fourth.

In 1939, Sun Valley hosted the nation’s first National Four-Way Open Tournament. Based on his downhill and slalom results, local ski instructor Peter Radacher won both the Harriman Cup and the Four-Way Open. Engen won the jumping event and finished fourth in the open.

In 1940, an invitational meet attracted 18 jumpers from 10 clubs. Engen made two flawless leaps to win. He turned aside the “keen challenge” of 21-year-old Gordie Wren of Steamboat Springs, who would go on to be a star of the 1948 U.S. Olympic jumping team and become the 1950 National Nordic Combined Champion. “Following the regular competition, the spectators were thrilled by double jumps, particularly the pair leap by Engen and Wren. ... The tournament was unlike others, where the contestants must make laborious climbs uphill to the scaffold, the chair-lift eliminating such strenuous going” (Sun Valley Ski Club Annual, 1939). In 1941, Engen beat Wren again in the third National Four-Way Open Tournament. Engen “displayed his supremacy in the air overwhelmingly” and “demonstrated his all-around skiing proficiency today by soaring to first place in jumping and winning the national four-event combined championship for the second consecutive year” (Sun Valley Ski Club Annual, 1941).

Alf Engen’s Legendary Battles with Torger Tokle

Torger Tokle emigrated from Norway in 1939. Before World War II he won 42 out of 48 tournaments and set three American distance records. Tokle was a power jumper. According to Harold Anson in Jumping Through Time, “his powerful, and precisely timed takeoffs provided him with a sufficient distance point to capture victories over more stylish jumpers.”

Club showcased Art Devlin, Alf Engen and

Torger Tokle. Community Library

Engen won the 1940 National Ski Jumping Championships, while Tokle finished fourth. At the 1940 National Four-Way Championships at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl, east of Seattle, Engen competed in all four disciplines, while Tokle competed only in jumping, where he made the longest distance. Engen won the jumping event on form points and the four-way title.

In 1941, at Iron Mountain, Michigan, Engen jumped 267 feet to break the North American distance record. Two hours later, at Leavenworth, Washington, Tokle set a new record of 273 feet. At the 1941 National Jumping Championships at Milwaukee Ski Bowl, Tokle jumped 288 feet to set his second North American distance record in less than a month. Engen was second. In 1942, Tokle bumped the record up to 289 feet at Iron Mountain.

The 1942 Harriman Cup/International Downhill and Slalom Tournament was won by Barney McLean “after a stiff battle with Alf Engen.” They tied at 268 points, but under Harriman Cup rules, the winner in case of a tie was the downhill victor. Dick Durrance was third, and Tokle did not enter.

Sun Valley’s jumping event that spring showed the skills of Tokle, Engen and a rising new star, Art Devlin of Lake Placid, New York. Devlin went on to become one of the country’s elite jumpers as a member of three U.S. Olympic teams (1948, 1952 and 1956) and the 1946 National Ski Jumping Champion.

Community Library

Ruud Mountain’s jumping hill was designed for 131-foot jumps, but in 1942 the takeoff was moved back 25 feet to allow for longer distances. Tokle’s “prodigious drive” set a new hill record of 188 feet, leaving “far behind the mark of 164 feet set by Engen, who reeled off a 175-foot jump.” Tokle “is a most powerful jumper and is constantly improving. Undoubtedly he has not yet reached his ultimate peak. ...” Afterwards, the competitors jumped in group formations, from two to eight in the air at one time. The Sun Valley Ski Club Annual, 1942, contained pictures of Engen, Tokle and Devlin demonstrating their skills.

On May 3, 1945, Sgt. Torger Tokle of the 10th Mountain Division was killed in Italy by an artillery shell.

Ruud Mountain after WWII

During WWII, Sun Valley served as a Naval Rehabilitation Hospital, where 6,578 Navy, Marine and Coast Guard patients were treated. The resort reopened in December 1946. Ruud Mountain saw less ski jumping, although it continued to be Sun Valley’s primary site for slalom events until 1961, often featuring side-by-side slalom courses for men and women.

In 1947, final tryouts for the 1948 U.S. Olympic Alpine teams for the St. Moritz Games were held at Sun Valley. Friedl Pfeifer’s slalom course on Ruud Mountain was “a championship course, typical of those in European competition.” Walter Prager and Engen were named co- coaches of the 1948 U.S. Olympic Ski Team. A ski jumping exhibition featured visiting Norwegian skiers Arnholdt Kongsgaard (1947 National Ski Jumping Champion), Fagnar Raklid, Harold Hauge and Gustav Raaum (an exchange student at the University of Washington), as well as established stars Engen, Durrance and Wren. The U.S. Olympic Jumping Team was selected at the Milwaukee Ski Bowl. The team then went to Sun Valley for two weeks of intensive training on Ruud Mountain.

The following year the jumping hill hosted intercollegiate meets and regional interstate meets, plus a junior championship and a Christmas jumping exhibition.

After the 1950 FIS World Alpine Championships at Aspen, racers came to Sun Valley for the National Downhill and Slalom Championships. Otto Lang set two side-by-side slalom courses on Ruud Mountain. A crowd of 400 turned out for a jumping exhibition, featuring University of Washington exchange students Raaum, Gunnar Sunde and Jan Kaier.

In 1951, Sun Valley hosted the final tryouts for the U.S. Olympic Alpine team for the 1952 Winter Games in Oslo, Norway. Side-by-side courses for the slalom events on Ruud Mountain had 32 gates for women and 40 for men. Chris Mohn and Sunde each jumped more than 150 feet in another exhibition of exchange student talent.

By this time, jumping had faded as a spectator draw, and the Ruud Mountain jump was used only for the annual American Legion Junior Three-Way Championships. The last jumping competition there came in 1956.

The 1961 Harriman Cup slalom race was the last held on Ruud Mountain, and it had special significance. Seventeen-year-old Billy Kidd won the slalom when Buddy Werner, winner of the downhill, fell but scrambled up to finish. Jimmie Heuga, also 17, won the Harriman Cup, with Kidd second and Werner third. Dick Dorworth said the 1961 Harriman Cup “will go down in history as the tournament in which youth manifested its right to compete on even terms with the elite of ski racing, as young American racers dominated the events.”

Ski Jumping at Ruud Mountain Ends with a Movie

In 1965, "Ski Party" was filmed at Sun Valley. A lightweight musical-comedy knock-off of beach party films, it starred Frankie Avalon and Dwayne Hickman, with an appearance by Annette Funicello, and musical appearances by Leslie Gore and James Brown. The absurd plot included Frankie Avalon going off the Ruud Mountain jump wearing an inflated clown suit and soaring like a helium balloon. This was the last recorded use of the ski jump. Maintenance records show the Ruud Mountain chairlift was last serviced in 1965, likely for the movie.

John W. Lundin has won four ISHA Skade Awards for books on the history of Pacific Northwest skiing and Sun Valley.