Article Date:

Monday, November 30, 2015

75 years ago, the Anchorage Ski Club and the U.S. Army teamed up to build the Arctic Valley ski area in Alaska. By Kirby Gilbert

Winter is coming! That’s the motto at Arctic Valley, a nonprofit ski area in south-central Alaska that for 75 years has been kept alive by members of the Anchorage Ski Club. Located 10 miles from downtown Anchorage, the small hill—with two chairlifts, a trusty 1960s T-bar and a vertical rise of 1,500 feet—is open to the public every winter weekend, attracting a dedicated band of families, plus skiers and riders who want to take a few runs at affordable prices.

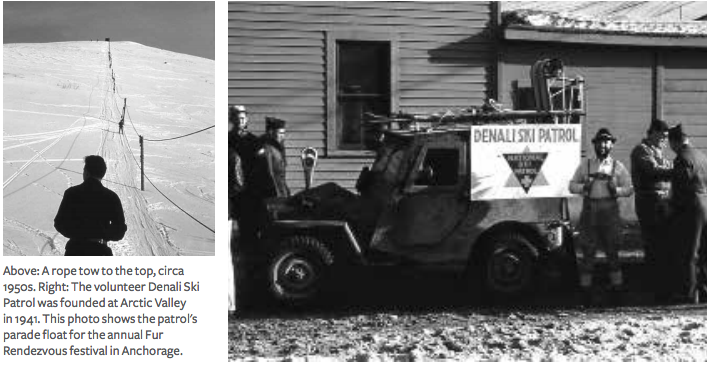

Arctic Valley’s unique history reaches back to the early 20th century, when Norwegian immigrants led the way in popularizing skiing in Alaska. Anchorage was the hub for their jumping and touring exploits, and early pioneers such as Ed Kjosen, George Rengaard and Ralph Solberg attracted followers to the sport. In 1935, civic leader Vern Johnson launched the Fur Rendezvous, a three-day winter festival featuring skiing, hockey, basketball, boxing and a children's sled dog race in downtown Anchorage. Nearly the entire population of Anchorage (about 3,000 back then) turned out for the annual bonfire and torchlight parade.

Arctic Valley’s unique history reaches back to the early 20th century, when Norwegian immigrants led the way in popularizing skiing in Alaska. Anchorage was the hub for their jumping and touring exploits, and early pioneers such as Ed Kjosen, George Rengaard and Ralph Solberg attracted followers to the sport. In 1935, civic leader Vern Johnson launched the Fur Rendezvous, a three-day winter festival featuring skiing, hockey, basketball, boxing and a children's sled dog race in downtown Anchorage. Nearly the entire population of Anchorage (about 3,000 back then) turned out for the annual bonfire and torchlight parade.As interest in skiing grew around North America in the early 1930s, it also caught on in Anchorage. A ski jump was built along the bluffs near downtown in 1936, and a year later, 35 skiers banded together to form the Anchorage Ski Club.

With American involvement in World War II ramping up, in 1940 U.S. Army troops started arriving at Fort Richardson and adjoining Elmendorf Air Force base in numbers. In November 1941, Colonel M.P. “Muktuk” Marston—armed with an official mandate to expand recreation opportunities and improve G.I. morale—took a handful of soldiers on off-duty treks into the mountains. They found wide-open slopes above timberline in the nearby Chugach Mountains, on a parcel of land that belonged to Fort Richardson. Marston led the effort to develop the site as a ski area for soldiers. Members of the Anchorage Ski Club helped to fund and build the first rope tows; they also started its Denali Ski Patrol. The military moved in Quonset huts to serve as day lodges and offered military ski gear for rentals. First called G.I. Slope or Fort Richardson Ski Bowl, the name Arctic Valley Ski Bowl eventually stuck.

After the war, several accomplished skiers arrived on the scene, including Hugh Bauer, a top performer in the Silver Skis races on Mt. Rainier and in races at Aspen and Jackson Hole. Hugh had been recruited by Dick Durrance to train paratroopers at Alta in early 1942. Hugh wrote a regular instructional column in the Anchorage newspaper and trained young members in racing technique. Chuck Hightower, a veteran of the 10th Mountain Division who in later years was a wellknown ski instructor at Aspen, was one of the top racers from club.

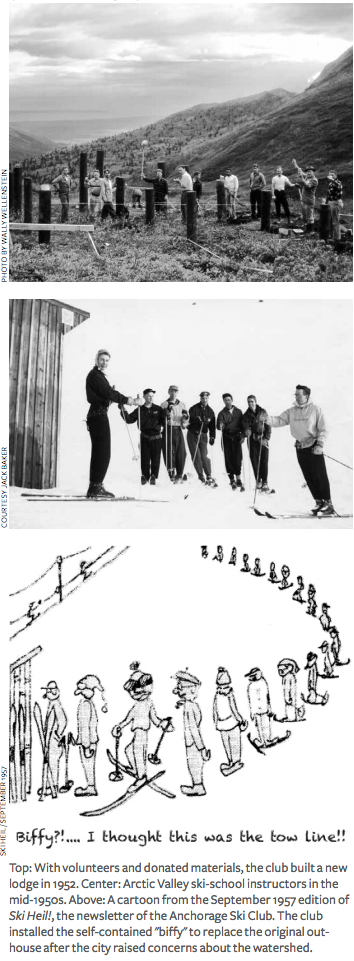

Before long, the ski club soon gained access to some adjoining non-military land and built its own lodge and three rope tows. The army tows ran five days a week while the ski club tows ran on weekends. Military personnel skied for free, and club members could ski the season for $10 per family.

Skiing on Army land was unique. Skiers had to sign in at a checkpoint, and the area occasionally was closed for military exercises and missile-firing practice. In early May, when the days were long and the temperatures moderate, the club would shut down the tows at 3 p.m. for salmon bakes, followed by after-dinner skiing until 9 p.m. “I’ll never forget those nights,” says ISHA charter member Jack Baker. He had arrived in Anchorage in 1946 to work in the post-war construction business; he quickly joined the club and soon led its volunteer ski patrol. “Sometimes in winter, we’d be skiing at 20 degrees below, with the Northern Lights flashing above.”

Army skiers initially outnumbered civilians by six to one, but that changed after the war, and club membership rose from 150 in 1946 to 480 by 1955. “That was quite a feat,” recalls Baker, “considering that the entire population of Anchorage was about 48,000 people.”

Baker says the club felt like family in those days, hosting social events like the Blessing of the Skis (a ritual conducted every opening day by Father Bartholomew, the Army chaplain), the annual Sitzmarker’s Ball, a winter carnival, a monthly meeting with a John Jay ski-movie screening, parties and outings—including a heli-ski excursion on Mount Alyeska in the late 1950s. As Anchorage grew as a hub for transcontinental air routes, the club staged competitions for crews on layovers, and the airlines donated free trips as fundraising prizes. The Head Ski Company gave the club its own franchise, so they could sell Standards to members at $75 a pair—Howard Head arranged the deal directly with Baker. In 1955, the club’s first woman president, Frances Vadla, started its popular monthly newsletter, Ski Heil, with news, cartoons, and recipes for local dishes like “crisp moose liver steaks.”

Running a ski area using volunteer labor was not easy. The club would start organizing work parties in mid-November to get the trails, lifts and lodge in shape; Baker recalls that the tundra was so spongy, they could ski on a few inches or snow or even a heavy frost. Every morning during the ski season, the rope-tow operators had to climb the slopes, lugging oil and gasoline for the motors. They continually—and often unsuccessfully—warned novice skiers not to ski over the dragging ropes. An editorial in the club newsletter, Ski Heil, expressed dismay about “careless skiers who slide their knife-edged skis across a three-thousand-dollar length of tow rope, rather than make the effort to pick it up and pass underneath.”

In 1955, the territorial health department tried to close down the ski area on the grounds that it was within the Anchorage public watershed and polluting the city’s water supply with effluent from its outhouse. After a long battle, Arctic Valley survived—and installed a deluxe, self-contained “biffy” to eliminate the chance of pollution getting into the surface water. The club’s “Biffy Ball” fundraiser, held on the second floor of the Elk Club, attracted so many people that the fire marshal showed up. “He asked us to quiet down,” recalls Baker, “so we started dancing waltzes, instead of polkas and the schottische!”

In 1955, the territorial health department tried to close down the ski area on the grounds that it was within the Anchorage public watershed and polluting the city’s water supply with effluent from its outhouse. After a long battle, Arctic Valley survived—and installed a deluxe, self-contained “biffy” to eliminate the chance of pollution getting into the surface water. The club’s “Biffy Ball” fundraiser, held on the second floor of the Elk Club, attracted so many people that the fire marshal showed up. “He asked us to quiet down,” recalls Baker, “so we started dancing waltzes, instead of polkas and the schottische!”In the late 1950s, the club saved up enough money to purchase a Dopplemayr T-bar. It took two seasons of volunteer labor to get it installed and operating. Initially, with just one operator stationed at the bottom, ski club members were instructed to pick up the phone at the top station and call the operator if they tripped the top safety gate.

By the early 1960s, competition for local skiers was getting stiff, as the new Alyeska Resort had recently opened in Girdwood, 27 miles from Anchorage. Still, the club and the military kept the Arctic Valley slopes open for another four decades. The club added its first chairlift in 1968 and a second in 1979. In 2002, it renovated the lodge and bought a groomer.

In 2003, the military got out of the ski business, razing its lodge and dismantling its chairlift. Meanwhile, the Anchorage Ski Club has continued to run Arctic Valley on 500 acres of land, with a small paid seasonal staff to run the lifts and lodge, a 15-person volunteer board, a new tubing park, and close to 500 members.

“We spend a lot of time and energy to keep the place going,” says volunteer Arctic Valley general manager John Robinson-Wilson, who works for HAP Alaska/Yukon in Anchorage. He spends about 10 hours a week volunteering for the club in summer and up to 30 hours a week in winter—not including the time he spends on the slopes. “We all hang out together in the lodge, and you definitely recognize a lot of the same people on the slopes every weekend. We’re all friends. That’s why we work so hard. It what makes Arctic Valley different.”

Kirby Gilbert is a ski historian in the Northwest, a Charter Member of ISHA, and a frequent contributor to Skiing History magazine. Jack Baker, a Charter Member of ISHA, contributed memories and research material to this article. Baker joined the Anchorage Ski Club and the Denali Ski Patrol in 1946.