There was more to Willy Schaeffler than stern disciplinarian.

By PETER MILLER

During the 1970-71 World Cup season, the men of the U.S. Alpine squad clashed with their coach, Willy Schaeffler. After Billy Kidd’s departure in February 1970, Spider Sabich was the team’s most successful skier. When he quit in January 1971 to join World Pro Skiing, the proximate cause was money—U.S. Ski Team racers earned none. But Sabich also butted heads with Schaeffler. In his book The 30,000-Mile Ski Race (1972), Peter Miller told both sides of the story.

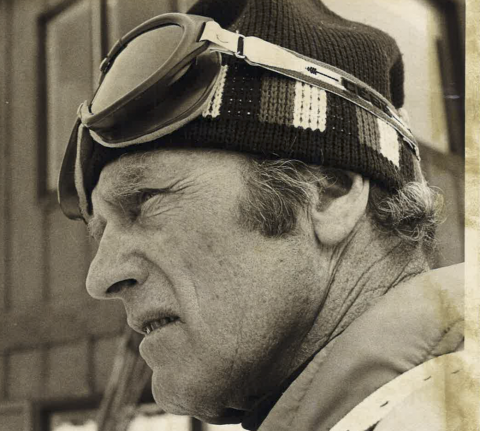

At fifty-four, their head coach, Willy Schaeffler, was a good generation gap older. His hair is grey, thin and combed straight back close to his skull. Part of his face seems to be paralyzed, so that his smile stops in the middle. Willy is a neat dresser and walks erect, almost stiffly. His blue eyes are appraising and sometimes appear quite cold. He spent the first half of his life in Germany, where he was born.

He had told the team earlier, when they were training in Aspen, Colorado, that he was the team hatchet man and that if someone had to be kicked off the team, he would do it, and he would be the scapegoat for all the difficulties. He had also told them that he was going to discipline their minds and bodies, and that although skiing is an individual sport, everyone must work together. He wanted to develop winners.

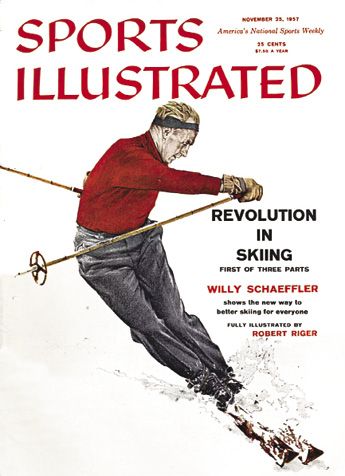

series of learn-to-ski articles

for Sports Illustrated.

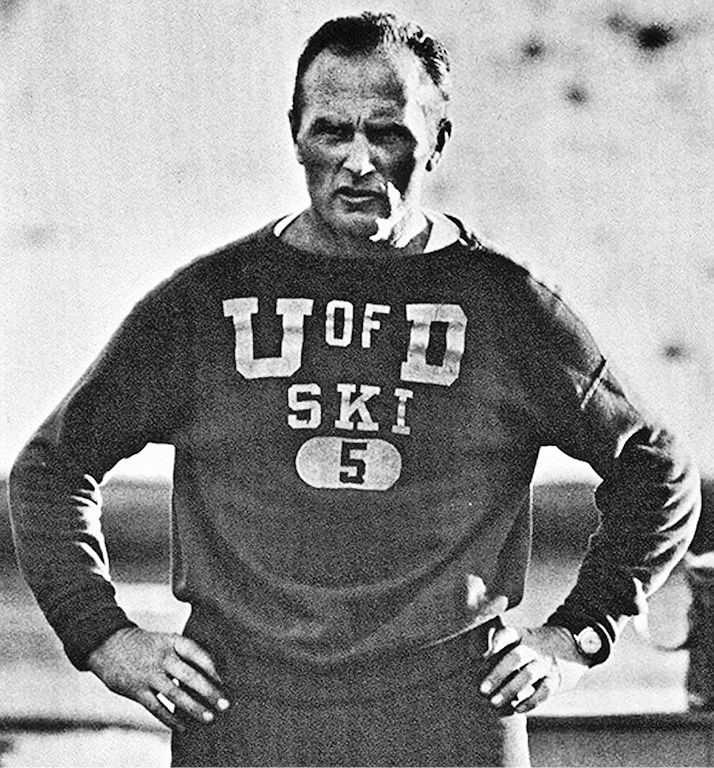

Willy has been a winner all his life. In his twenty-two years as the coach at the University of Denver his ski teams won 100 out of 123 dual meets, and 14 National Collegiate titles. For a while, his archrival was Bob Beattie, who, before he became one of Willy’s predecessors as National Ski Team coach, trained the ski team at the University of Colorado. Willy beat the pants off Bob. Most of the team did not appreciate Willy’s authoritarian attitude toward ski racing. . . .

The two months during which the young racers had lived and trained under their new coach had convinced them he was an autocratic disciplinarian. They called Willy a heavy-handed Kraut. What few of them realized was that Willy, like them, had started his life as an avid skier who disliked authority, discipline, regimentation, and the draft. During World War II, Willy’s rebellion against the political-military establishment in Germany nearly cost him his life half a dozen times.

Willy was raised in Bavaria, not far from Garmisch, where he learned to ski. His father was a Social Democrat, and since Hitler was not very well disposed to political opponents in the mid-thirties, the father was placed on the blacklist. Willy was drafted in 1937, and in a letter to an uncle in Chicago he described some of his training. The letter was censored. Then the government extended his Army duty, two weeks before he was to be discharged. Just as any American youth would do, Willy bitched, loud and clear. The Army brought forth the letter and accused Willy of being a spy. They criticized him for lack of patriotism. As Willy was not in the Party, and his family was blacklisted, they busted him from warrant officer to private and sent him to the Dutch border to what was called a baby concentration camp. For the next year and a half, he dug ditches from 5:00 a.m. until 4:00 in the afternoon. He was twenty-one, the same age as most of the racers he now coaches.

Willy was released in 1938 and started to live a happy period as a test driver for the Ford Motor Company. On weekends and holidays, he was a Garmisch ski instructor. When the war broke out, his presence on the blacklist saved him from being drafted. But the Army reconsidered in 1941 and inducted him into the ranks as part of a penal battalion. The battalion was sent to Poland to build bridges. When the offensive into Russia began, Willy’s penal battalion was offered a chance to rehabilitate itself. The men were given weapons and were used as special patrols and on spearhead missions. Willy was somewhere behind Moscow, as part of a pincer movement, when the temperature dropped to -54 degrees and the Russians began to pull the Germans apart. Willy put on the clothes of dead Russians. He was captured and lined up before a firing squad. He went through a very quick and intense period of concentration, where his life flashed in an instant. They fired and Willy, sure he was dead, fell to the ground. The Russians, drunk on vodka, fell down too, laughing madly over their practical joke. Willy managed to escape and rejoin the Germans. His life on the Russian front was probably saved by his fifth wound, shrapnel in the right lung and upper heart chamber. He was evacuated in a plane, which was shot down behind enemy lines. Willy, one of two survivors, hid in a small compartment for two days before he was rescued. He was transferred from one hospital to another until he arrived in Munich, weighing 130 pounds. It was 1944.

led the DU Pioneers to 14 NCAA

titles. University of Denver photo

The military establishment decided that Willy, after he gained twenty pounds, was so well trained in winter warfare that he could rehabilitate himself again by returning to the Russian front. Willy silently refused. At about the same time, American Flying Fortresses blasted Munich. The headquarters building was evacuated before the raid, but Willy and a friend lingered and filled a knapsack with code numbers, passes, stamps, requisition orders. The building was demolished by bombs five minutes after Willy rifled the offices. A day later, Willy and his friend were dug out of a nearby bomb shelter. No one would ever know that the papers were stolen. Willy split for Austria.

He could, with the papers, go anywhere, requisition guns and munitions, food and uniforms. He entered the underground, harassing the German Army with sabotage. His biggest coup was in 1944, when Hitler ordered a last stand at St. Anton. Tanks, cannons and supplies were brought in by train from Germany through the Arlberg Tunnel, and the guns were being dug into the lower slopes of St. Anton—where today there are ski slopes. Willy blew up the tunnel with a box of dynamite and for the rest of the winter, from his hideout on the Valluga mountain, watched German troops struggle over the Arlberg Pass.

After the war Willy fished out a few top Nazis who were hiding in Austria and managed to land his old job at Garmisch, ski instructing American troops. One of his students was General George C. Patton. They became friends and Patton helped Willy, who had been living for two years on forged identifications, to receive official papers and the goodwill of the U.S. military.

cost Schaeffler his life, several

times. He emerged with a fierce

will to win. USSSHOF

World War II is history; the emotions of that period are lost on the younger generation. Yet perhaps it is the residue of that period of hardship that has forged this particular generation gap, the difference between the easygoing young American ski racers and the older, German-born, adopted American. Willy developed, in his younger days in Bavaria, as an independent thinker who believed in self-determination and who loved to ski. His beliefs, and they were as strong as are the anti-Vietnam war protests of the youth today, turned him into a rebel against authority, the establishment, draft, right-wingers. He developed his own philosophy, survived against the odds, and became a person who dislikes criticism and who is uncompromising in his beliefs. When he was twenty-one, the average age of the American ski racer, he was, because of his independent, outspoken attitude, digging ditches in a concentration camp. In fact, Willy, a German who sabotaged the war effort of his own country, has all the qualities that the young Americans think are so cool. The difference is that Willy was nearly killed a number of times because he adhered to what he thought was correct. Discipline and physical stamina and the will to win, or survive—that which he hopes to instill in his young American skiers—kept him alive. Money, prestige, security were luxuries he never knew in his youth.

Willy Schaeffler was elected to the U.S. Ski Hall of Fame in 1974. After repeated cardiac surgeries, his heart gave out in 1988. He was 72 years old.

Peter Miller joined Life Magazine as a writer/photographer in 1959 and went on to write and shoot for dozens of national magazines, including Sports Illustrated and, from 1965 to 1988, SKI. He has written ten books. In 1994 he received ISHA’s Lifetime Achievement Award in Journalism.