An outraged IOC czar, an impenitent ski racer. Their loathing was mutual.

BY JOHN FRY

Prize money in a single World Cup race is now in six figures. Competitors openly negotiate contracts to promote skis and boots and snowboards, and earn mega-buck bonuses for winning Olympic medals. Commercialized racing on this scale didn’t exist under the FIS (Federation Internationale de Ski) 45 years ago, and prize money was forbidden. Nonetheless, at the 1972 Winter Games in Sapporo, Japan, members of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) regarded ski racing as so tainted by money that it perhaps no longer belonged in the Winter Games.

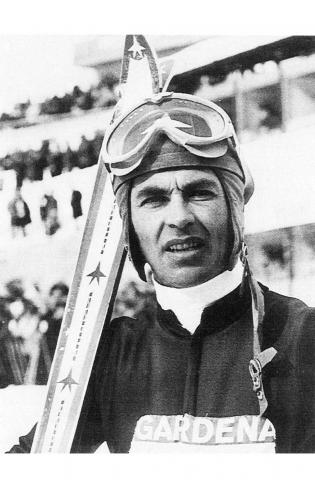

At the storm’s center were IOC president Avery Brundage, a wealthy, autocratic American businessman, and Austrian racer Karl Schranz, two-time overall champion of alpine World Cup skiing and a favorite to win the Sapporo downhill. Their loathing was mutual. An outraged Brundage saw Schranz as someone who had to be ejected because he stood for the professionalism that would ruin the Olympic movement. An impenitent Schranz mocked the wealthy Brundage, branding him a hypocrite for denying athletes the opportunity to make money from their sport. Today, surveying the often obscene array of corporate logos smothering clothing and banners at Olympic sports venues, the dispute seems laughable. But it attracted world-wide attention at the time.

For some, the story began in 1968 with another controversy. . . perhaps the greatest surrounding the finish of any ski race ever held. Karl Schranz was again the central character. On the final day of the Winter Olympics above Grenoble, France’s national hero Jean-Claude Killy was poised to win the last of the three alpine skiing gold medals. The conditions for the slalom, however, were atrocious. Fog shrouded the course. Gatekeepers often could not see if a racer had made it around a pole. Racing in the second run, Schranz claimed a figure crossed the course and interfered with his descent, although no official saw anyone. Climbing back to the top, he received permission to re-start his run, and beat Killy by a full half-second. Within hours, though, the jury disqualified him. The next day, I attended a press conference organized by the Kneissl ski factory for Schranz so he could protest his gold medal loss. It was an act that specially irritated IOC chief Brundage, who had earlier attacked the commercial relations between ski manufacturers and racers.

In the four years between the French and Japanese Winter Olympics, the FIS did little to appease Brundage. Among all the sports federations concerned with finding ways to allow athletes to earn money, the FIS proved itself the most inventive and liberal. It began to permit national ski federations, for example, to organize the present-day manufacturer pools through which sponsors funnel money to racers. In return, it allowed the racers to wear commercial logos.

To Brundage, all this was a clear violation of Olympic standards. At 84, after running the IOC for 20 years, he was determined to end the commercial abuses of skiing. . .if necessary, even by throwing as many as 40 of the leading racers out of the Olympics. Not surprisingly, the skiers kept a low public profile.

Except for Schranz. He attacked Brundage and his wealthy, senescent Olympic Committee members directly. “How can they understand the situation of top ski racers,” he asked the press, “when these officials have never been poor?” That was enough for Brundage, who easily persuaded the IOC to to expel him from the Olympics.

Back in the Tyrolean Alps, prodded by incendiary newspaper headlines, infuriated Austrians called for their racers to leave Sapporo and come home in sympathy. But they didn’t. The tough, embittered Schranz was not popular with his teammates, despite his ranking as the number one alpine skier of the post-Killy era.

When the racers didn’t return, threats were made to burn down the home of the Ski Federation’s chief. Another official’s children were beaten up at school. Austrians perceived Schranz as a hero from a small country, bullied by bigger nations. Stores were flooded with Schranz T-shirts. When he flew back to a parade in Vienna, a horde of 200,000 people welcomed him home, chanting “Karl is richtig, Brundage is nichtig.” A beaming Schranz raised his arms in vindication.

The ski events at Sapporo took place on schedule. Petite Barbara Ann Cochran won America’s only gold, in the slalom. Brundage died in 1975. Efforts by International Management to market Schranz in America failed . . something of an irony. Today he operates a small hotel in St. Anton. To anyone timorous enough to ask, he will affirm that he was robbed of his gold medal in 1968 and that Brundage was wrong.

The truth? I’m certain he never won the Grenoble slalom.

On the other hand, Schranz-- a leftist with a keen sense of class strife -- won the battle to allow succeeding generations of skiers the right to make money. He also helped open the door for legions of sports marketers, lawyers, athlete agents, product sponsors and manufacturers, to say nothing of conflicted IOC officials, to make millions. Is this progress? No. Despite the influx of big money, ski racing was as exciting without it as with it.