How a young freestyler snapped up a prime piece of Squaw Valley property—right out from under Alex Cushing. By Eddy Starr Ancinas

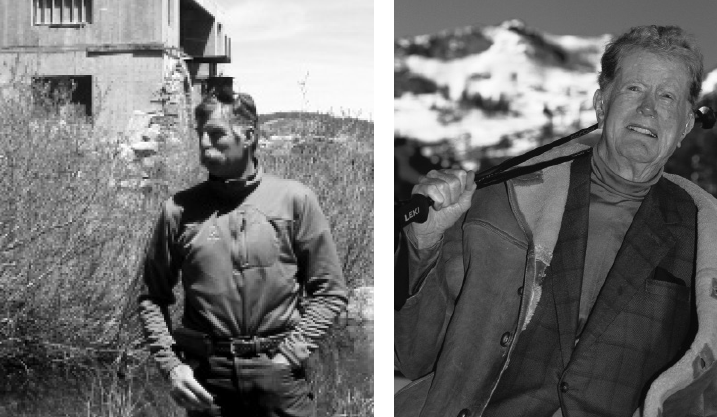

In 1989, Troy Caldwell (at left; shown here in May 2014, courtesy of www.snowbrains.com) purchased a piece of property for $400,000 from Southern Pacific Land Company. Squaw Valley founder Alex Cushing (right, courtesy of Hank De Vre) had been hoping to acquire the property for years, but missed the chance when a company accountant mistakenly declined an offer to purchase it.

Troy Caldwell was 19 years old in 1970, when he got a job selling tickets at Alpine Meadows, California, where he had come to perfect his freestyle technique. By 1972, he had joined the international circuit on the U.S. Freestyle team, competing with Sandra Poulsen, Wayne Wong, John Clendenin and local pal Rudy Zink. Early in his career, he met his future wife, Susan, who happened to live nearby in Homewood, and before long, she also worked at Alpine.

Troy, having studied architecture in college, worked as a contractor in summer months. By 1989, he had built two houses in Alpine Meadows—renting one and living in the other. Susan, now in charge of Special Tickets, knew every season pass holder, former stockholder and just about every regular customer at Alpine by their first name, and her smile and effusive greeting typified the friendly face of Alpine. Like many young couples who love to ski and love the mountains, they began to think about owning their own business, and they decided they saw a need they could fill: Alpine Meadows had no overnight accommodations, so wouldn’t a bed and breakfast be a great idea?

“Something fancy, like Stein Eriksen’s lodge,” Troy thought. “We’d serve them at the bar, entertain them. We’d have a ski shop and a surface lift to take them to Alpine,” he added, reminiscing about their original plan.

They thought a good location would be just above the road before you enter the parking lot. Troy discovered the land was owned by Southern Pacific Land Company (SP), so dressed in his very best “mountain attire,” he went to their office at Number One Market Street in San Francisco. “When I looked up at those two 14-foot chrome doors, I said, ‘what am I doing here?’” Troy remembers.

More determined than daunted, Troy introduced himself and was ushered into Brandon Mark’s office. “I know you guys own the property next to Alpine Meadows,” he began, “and I’m interested in buying a little corner of that property.”

“Well, there’s good news and bad news,” Mark replied. “Bad news—we can’t sell you a little piece of that property. We’re not allowed to sub-divide it. The good news is, your timing is great. Right now we are in negotiations with Catellus [a mixed-use real-estate development corporation] to get rid of all of SP’s property, and anything we can sell outright, before any transaction with Catellus, is money in our pocket.”

Mark showed Troy a map of SP’s holdings in California—a well-documented checkerboard of land the railroad company had been granted from the federal government in the 1800s. In 1987, SP began selling off large tracts of land in North Lake Tahoe—and two years later, in walked Troy Caldwell.

When Mark showed Troy a 144-acre parcel of land in the lower section, Troy said, “No way can we afford that,” but Mark urged him to consider it.

“You may be surprised,” he said.

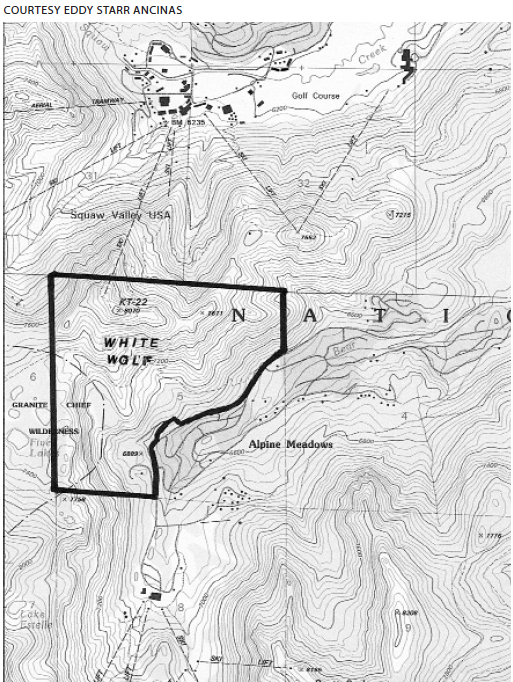

Before they had time to think about how they could afford the 144-acre parcel shown on a Placer County map, the county advised them it wasn’t a true parcel. The only thing SP could sell them was the whole 460-acre section—the same section that Alpine Meadows founder John Reily had leased from SP in 1958, then relinquished in a quitclaim in 1975.

“No way can we afford that,” Troy repeated.

“What happened to our dream of a B&B for $40,000 to $50,000?” Susan asked. “Now we’re talking hundreds of thousands.”

“This is worth it, Susie. Let’s go for this thing,” was Troy’s reply.

For obvious reasons, Squaw Valley founder Alex Cushing had been waiting for years to own the land under his lifts that he had been leasing first from Reily and then from SP. Cushing had bargained over the terms of the lease agreement with SP for years, and they were well aware of his interest in acquiring the land. Therefore, when SP called Squaw Valley Ski Corp. to inquire if they would like to purchase Section 5 including the 70 acres in Squaw Valley, they must have been surprised when the accountant who took the call said, “No thanks. We rent it so cheap I don’t think we’re interested.”

No one could have been more surprised, however, than Cushing, when SP notified him the following month to send his next rent check to Troy Caldwell.

“Who is this guy?” Cushing asked when he called resort owner Nick Badami at Alpine. Badami assured Cushing that Troy Caldwell was not a real estate developer, just a young freestyle skier with big ideas; so Cushing called Troy and invited him to lunch.

According to Troy, it was a pleasant, friendly lunch, and Cushing listened with interest (perhaps disbelief) to Troy’s story about why and how he bought the land out from under Cushing for just under $400,000.

Troy and Susan call the first four years their “Daniel Boone years,” as they struggled to build a road and move their trailer from the campground to their property before winter set in. An early October snowstorm caught them with frozen water lines running from a spring over the snow to the trailer, a generator that ran out of gas in half an hour, and an oven only big enough for a cupcake. During those four years, they began to build their house on a flat area at the base of KT’s backside. Although Alpine ski patrol director Larry Heywood had checked the area for avalanches, they were never sure it was safe; but they knew enough to get out, if danger seemed imminent. Troy remembers digging down eight feet to the top of his trailer.

“We were just surviving,” Troy recalls, “no water, no power—sometimes the only vehicle we could use was our bulldozer.”

When summer came, thoughts returned to what they would do with their property, now called “White Wolf.” In an effort to get Alpine involved, Troy invited Badami and his colleagues, Howard Carnell and Werner Schuster, to a catered lunch served under the pines by the creek near his future home. Badami and Schuster were currently involved in developing a new ski area at Galena Summit near Reno, where Troy and Susan had considered owning and operating a B&B, but after attending months of public meetings, Troy picked up on the sentiment, “why develop new areas—better to expand the existing ones.” Troy could see the logic, and said to Susan, “Hey, why not here in Alpine?”

The property lies between Squaw Valley and Alpine Meadows, off the backside of Squaw. It includes 75 acres of Squaw Valley, including the top of the Olympic Lady and KT-22 chairlifts

Badami suggested a “Fat Camp” or spa with outdoor exercise, a rock climbing camp. He and Schuster thought perhaps the area could connect to Squaw Valley, and they wondered about the increased traffic in Alpine.

The realization that 460 acres of granite cliffs, stately pines, chutes and gullies, steep and gentle slopes, mountain trails and wildflowers galore in spring was perhaps worthy of something more than a little B&B, inspired Troy and Susan to expand their dream to a 52-room luxury hotel. Of course, Troy would design it in his favorite architectural style—avalanche and fire-proof concrete. Then, thinking really big, a ski area in his front yard seemed like an even more worthy project.

Like Poulsen, Reily and even Cushing before him, Troy Caldwell had realized a dream that would be his life, with many unexpected consequences (and a few nightmares).

It was only a matter of time until Cushing called his landlord to renegotiate the terms of the lease that Troy had inherited from SP. Although the 2014 termination date was about 18 years in the future, Cushing wanted to get started on a new lease now. Troy, still unsure of his future plans for a ski area at White Wolf, didn’t want to sign anything just then. In 1996, after recalculating their agreement, Cushing filed a suit for breach of contract, claiming he had “over-paid” on his lease.

While Troy hired and paid lawyers to work on that one, the two men entered into an agreement to trade 70 acres of Troy’s land in Squaw Valley for the three year-old Headwall triple chair lift—towers, chairs and cables, to be delivered over the hill by helicopter for Troy to install on his side of KT. Cushing would have his land back, and Troy his lift. However, after signing the contract, Cushing decided that was too good a deal and changed it to the 30-year-old double Cornice chair lift. Troy sued Cushing for breach of contract.

When the Placer County Planning Commission issued the Caldwells a conditional use permit to install a chairlift on their land in November 2000, Troy went to work in his garage-cum-lift manufacturing plant, with the help of a welder who once worked for Doppelmayer, and a chairlift engineer formerly employed by YAN Engineering. While they worked to build and assemble the 17 towers, cross frames and terminals for the next nine months, few people knew what Troy was doing; but as soon as the towers could be seen climbing 1,123 feet up the mountain from Alpine to Squaw, heads turned and the Bear Creek homeowners sued Placer County for issuing Troy the permit. That one hurt, as Susan had worked for over 20 years in Alpine, and they both considered themselves members of the Alpine community. Troy stopped working on the lift in 2007 and it has never been in operation.

The Caldwells compromised with Bear Creek and the ski area, agreeing they would not sell tickets, and access from Squaw Valley would be denied. Further restrictions allowed them only 25 “friends or family” on the mountain at a time, and skiers had to take a first aid course and be avalanche certified, carrying beacons, probes and shovels.

With these restrictions, White Wolf became the second private ski area in the country after the Yellowstone Club in Montana. Operating his area much like a heli-ski operation (without the fancy lodge—yet), Troy’s skiing friends have joined him on limited snowcat rides up the mountain, descending in a spray of fresh powder or exploring the terrain on firm spring corn. With its southeast exposure, the season is limited compared to neighboring Alpine Meadows.

Troy won his suit over the exchanged ski lift with Cushing, and after fourteen years of trying to bring the young entrepreneur to his financial knees, Squaw Valley Ski Corp. relented. Troy believes they were preparing to sell Squaw Valley, and needed to get rid of what Troy’s attorney called “nuisance suits.”

With no more legal battles, a cozy home and towers in place, Susan and Troy’s dream was just beginning.

This article is excerpted from Tales from Two Valleys: Squaw Valley and Alpine Meadows by Eddy Starr Ancinas. The book won an ISHA Skade Award in 2013. Eddy, the descendant of a California ski and mountaineering family, was a guide for the IOC in Squaw Valley at the 1960 Olympics, where she met her husband, Osvaldo Ancinas, a member of the Argentine ski team.

Will Squaw and Alpine Finally Connect?

Wirth (left) and Caldwell during a recent interview. Courtesy of Eddy Starr Ancinas.

In a recent interview with Skiing History, resort CEO Andy Wirth and Troy Caldwell say it will happen within five years.

In November 2010, Squaw Valley was purchased by KSL Capital Partners, a private equity firm. A year later, Squaw and Alpine Meadows merged under the new leadership of Squaw Valley Ski Holdings, LLC. The company operates as a single corporate entity, with joint lift tickets and free shuttles between the two resorts. But while you can catch a ride between the villages, you can’t ski from one to the other.

Connecting Alpine and Squaw via ski trails and chairlifts has been a vision shared by Wayne Poulsen, John Reily and Alex Cushing since the 1960s. Troy Caldwell’s property lies directly between Squaw and Alpine, off the backside of Squaw. It includes 75 acres of Squaw Valley, including the top of the Olympic Lady and KT-22 chairlifts.

“The vision has existed for [decades],” said Andy Wirth, president and CEO of Squaw Valley Ski Holdings, when I sat down with him and Caldwell to hear their plans. “The vision is easy. The challenge is to make it happen in a logical way.”

The project requires working closely with the U.S. Forest Service, Placer County and government agencies, and taking into account environmental studies and the needs of private landowners.

“You would think it would be easy with these two mountains so close together,” Wirth said, “but if it were that easy, they would have done it years ago. We haven’t been just staring at maps. Troy and I have visited lots of ski areas together—comparing notes on terrain, lift integration, area management—asking ourselves, what would they change after years of operation?”

Wirth said they’re working with “the best mountain planners in the world,” studying up to 20 scenarios. “We have to look seriously at all lift and gondola connection options...our industry is littered with lifts that shouldn’t be there.”

Having studied weather and wind patterns with relation to hours of lift operation and avalanche mitigation, both men agreed they are in “the last stages of deciding.” They anticipate that the project will be completed within three to five years and that it will involve Caldwell’s property.

“Andy and I are going to make this happen,” Caldwell vowed. —Eddy Starr Ancinas

To watch a May 2014 interview with Caldwell and journalist Miles Clark on the Website SnowBrains.com, go to: http://snowbrains.com/will-squaw-alpine-connect-exclusive-troy-caldwell-video-interview/