Article Date:

Monday, June 12, 2017

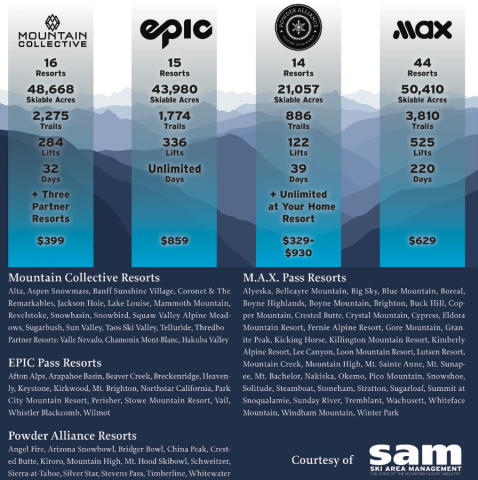

Photo Caption: This chart, compiled by the staff at Ski Area Management, shows the price of the nation’s leading multi-resort season passes. Adjusted for inflation, these passes provide high-frequency skiers with per-day prices that rival those of the early 1950s.

Multi-area season passes have brought back 1950s prices. By John Fry

Next winter the price of a season-long pass to ride an unlimited number of days on Stowe Mountain Resort’s lifts will be cut in half to $859. For someone skiing or snowboarding 20 days, for example, the per-day cost will be $43. Adjusted for inflation, that’s equivalent to $4.25 per day in 1951—about what a one-day ticket at Stowe’s Mount Mansfield cost 67 years ago.

Mt. Mansfield could charge a premium then because it had a chairlift. The majority, hundreds of ski hills, offered only rope tows in 1951, and the average one-day ticket, nationally, cost only $2.50. Skiing has never been cheaper than that. But the experience was vastly different: Compare today’s high-tech snowmaking and high-speed lifts to the 1950s ordeal of grabbing onto a fast-moving rope, skiing on ice, crud over rocks, or maybe no snow at all.

The Multi-Resort Season Pass

Between 1951 and 1965, ski areas jacked lift ticket prices at triple the rate of inflation so they could invest in chairlifts, snowmaking and grooming. Then came high-speed detachable chairs, more sophisticated snow management, and handsome day lodges with WiFi connections, and the one-day lift ticket at big resorts leaped to over a hundred bucks.

Now something different is happening.

A skier or snowboarder can avoid paying the lofty posted price of a daily lift pass by purchasing from a varied assortment of season passes. High-frequency skiers and snowboarders who buy Epic, Max and Mountain Collective season passes (see chart on the next page) are now paying miraculous 1950s and 1960s prices for a day on the slopes.

At Squaw Valley, the California resort’s one-day lift pass over the past 37 years soared to $124. But for high-frequency skiers and riders who buy a season pass, that hyper-inflation is gone. Today Squaw Valley sells a pass with unlimited skiing for $899, which itself is 30 percent less than it would have cost in inflation-adjusted dollars 37 years ago.

A college student can now enjoy unlimited skiing at Squaw Valley, for the entire winter, for only $469. A kid who skis only 10 days is thus paying about the same amount as he would have paid using Squaw Valley’s day pass of the 1950s, adjusted for inflation.

Among skiers benefiting are more and more retired folks—Baby Boomers who caused the sport’s explosive growth in the 20 years after World War II. They have more time to ski. A 72-year-old skier averages 13 days per winter on the slopes, according to RRC Associates, which conducts on-slope interviews and research for the National Ski Areas Association (NSAA).

Aspen and Vail

The Mountain Collective Resorts group, whose 16 members include Aspen, Mammoth Mountain, Jackson Hole and Lake Louise, enables someone to ski or board two days at each resort for $429, according to Ski Area Management. Thus someone skiing only 12 days at six of the resorts would be paying $36 a day, compared with the resorts’ typical one-day lift pass price of over a hundred dollars.

A season pass at Aspen costing $475 in 1988 more than quadrupled over the next 28 years to $2,119. That upward trend may have come to an abrupt halt. The Aspen Skiing Company has joined with KSL Capital Partners, owner of Squaw Valley, to acquire Mammoth Mountain and Intrawest’s ski areas, fully intent on competing against Vail’s bargain-priced Epic pass.

Vail Resorts, now the owner of Whistler Blackcomb in British Columbia, recently purchased Stowe Mountain Resort, which allows skiers and snowboarders there to buy a local Epic pass. If purchased now, it would enable an adult to ride Mount Mansfield’s and Spruce Peak lifts only, for an unlimited number of days in 2017–18 for $639. Last winter, the same kind of pass would have cost $1,860.

When Does a Season Pass Pay Off?

On average nationwide, how long does it take for a season pass to pay for itself . . .that is, be less than a ski area’s leading adult one-day pass price multiplied by number of days skied? According to RRC Associates, it took 17 days in 1997 for a season pass to pay off; in 2015–16 the number was cut by almost a half, to 9.2 days to payoff.

The result? Now 1.6 million out of 8.4 million U.S. skiers and snowboarders have the potential to save money buying a season pass, double the number 20 years ago. (The frequency statistic does not include skiing by resort employees).

Dynamic Pricing

That still leaves the majority of skiers subject to day and short-term lift pass prices. According to ski resort consultant and ISHA director Chris Diamond, more and more resorts are “dynamic pricing,” following the practice of Uber and airlines, which vary prices based on demand, and time in advance of purchase. Buy early, pay less applies to ski season passes as well. The later a skier purchases a pass, the higher the price.

Ski areas are giving away with one hand, taking away with the other.

ISHA chairman John Fry is the author of the award-winning The Story of Modern Skiing, newly available as an e-book. In 1954, SKI Magazine paid him $75 for his first published article, worth $680 today.