Article Date:

Monday, June 12, 2017

Photo Caption: On April 19, 2017, The New York Times published an article by Kade Krichko titled “China’s Stone Age Skiers and History’s Harsh Lessons.” The article recounts the history of skiing in China’s remote Altai Mountains and the efforts to preserve its traditions while fostering a modern ski and tourism industry. The piece was prominently featured in print and online and likely reached more than one million readers.

In the article, Kade gives well-deserved acknowledgement to Shan Zhaojian, the father of modern skiing in China, as well as its chief ski historian. Shan is also the leader of the movement declaring that skiing originated here, thousands of years ago—a viewpoint that has sparked debate among historians. To read the article, go to: www.nytimes.com/2017/04/19/sports/skiing/skiing-china-cave-paintings.html?_r=0

Did skiing originate in the Altai Mountains of China? A recent New York Times article reignited the ongoing debate. STORY AND PHOTOS BY NILS LARSEN

In January 2015, I attended an international ski history conference in Altay City, China. The event was organized by Shan Zhaojian and Ayiken Jiashan, a multilingual guide, translator and educator from Xinjiang province.

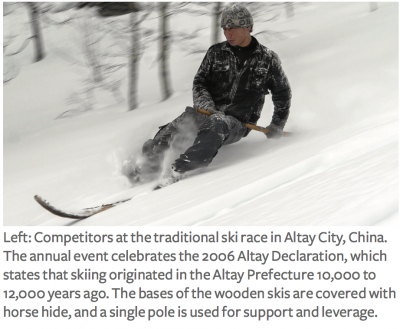

In the course of his work, Shan had became aware of several indigenous skiing populations in the nation’s northern regions. The largest and most active of these tribes live in the Altai Mountains of Xinjiang, between Mongolia and Kazakhstan. In January 2006, Shan and his associates, including longtime archaeological researcher Wang Bo, issued the Altay Declaration, stating that the Altay Prefecture in China was the world’s birthplace of skiing, some 10,000–12,000 BP (Before Present). Needless to say, this declaration has stirred controversy in the West.

I first met Shan in Beijing in 2006, and again in 2007 at the traditional ski race in Altay City, an annual event that celebrates the declaration. We shared a strong interest in preserving the traditional skiing still found in the Altai Mountains, and with the help of Ayiken (my translator of both language and culture), we became friends, exchanging information and ideas on the Altai skiers and ways to support their ski culture. Though we were in agreement on the uniqueness and importance of the region’s ski traditions, we differed on the Altay Declaration. The main piece of physical evidence supporting the declaration are some cave paintings found near Altay City that appear to depict skiers in motion over a collection of wild animals. The paintings are wonderful, both in their location deep in the hills and in their execution. The dating, however, seemed problematic, and in talking to experts in the U.S. the difficulty in dating rock art was universally emphasized.

I first met Shan in Beijing in 2006, and again in 2007 at the traditional ski race in Altay City, an annual event that celebrates the declaration. We shared a strong interest in preserving the traditional skiing still found in the Altai Mountains, and with the help of Ayiken (my translator of both language and culture), we became friends, exchanging information and ideas on the Altai skiers and ways to support their ski culture. Though we were in agreement on the uniqueness and importance of the region’s ski traditions, we differed on the Altay Declaration. The main piece of physical evidence supporting the declaration are some cave paintings found near Altay City that appear to depict skiers in motion over a collection of wild animals. The paintings are wonderful, both in their location deep in the hills and in their execution. The dating, however, seemed problematic, and in talking to experts in the U.S. the difficulty in dating rock art was universally emphasized. Shan sincerely believes that skiing’s origins are to be found in the Chinese Altai, while I hold that skiing in the region is indeed very ancient and that the Altay area might be a place of origin. Indeed, the first written description of skiing is about skiers in the Altai Mountains (Western Han Dynasty, 206 BC to 24 AD), and the legendary Norwegian skier and writer Fridtjof Nansen points to the Lake Baikal/Altai region as the possible origin in his 1890 book First Crossing of Greenland.

The ski history conference in 2015 was scheduled to overlap with the annual races in Altay City, and all attendees were given a firsthand view of traditional skiing, as well as the cave paintings. Before the last day, Shan approached a few of us about a final declaration of agreement for attendees to sign. Initially, the document read as unequivocal support for the 2006 declaration, something most of us from the West were not willing to sign. Karin Berg, the longtime director of the Holmenkollen Ski Museum in Oslo, was the standout diplomat in recrafting the text. After many hours of intense debate and multilingual rewrites, Shan, Ayiken, Karin and myself settled on a text that emphasized the region’s ancient skiing history and the truly unique use of traditional skis and technique still practiced there.

In May 2017, Ayiken gave me an excellent paper written specifically on the rock pictographs that support the Altay Declaration. The paper (Naturalistic Animals and Hand Stencils in the Rock Art of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Northwest China) was published in 2016 and is written by Paul Taçon (Australia), Tang Huisheng (China) and Maxime Aubert (Australia), all experts in the study and dating of rock art. They suggest that the paintings are probably 4,000 to 5,250 BP. Ancient indeed, but likely not as old as the 10,000+ BP used by the 2006 declaration. This analysis is also not definitive, but it is the most detailed examination of the paintings to date.

In May 2017, Ayiken gave me an excellent paper written specifically on the rock pictographs that support the Altay Declaration. The paper (Naturalistic Animals and Hand Stencils in the Rock Art of Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, Northwest China) was published in 2016 and is written by Paul Taçon (Australia), Tang Huisheng (China) and Maxime Aubert (Australia), all experts in the study and dating of rock art. They suggest that the paintings are probably 4,000 to 5,250 BP. Ancient indeed, but likely not as old as the 10,000+ BP used by the 2006 declaration. This analysis is also not definitive, but it is the most detailed examination of the paintings to date.If skiing, as it seems possible, dates back 10,000 years or more, identifying a precise point of origin (or origins) will be difficult at best. Nansen’s regional point of view seems much more likely. These “first” discussions often get bogged down in politics and national pride and can elevate the “when” over the much more useful study of “how” and “why.” China provides only the latest example of this focus on “first.” Since the emergence of skiing in greater Europe in the late 1800s, Norway has often been considered the birthplace of skiing. Norway has promoted this view and it is a point of national pride.

In digging into the subject of ancient skiing, I have found very little original research that stretches beyond our view of skiing as a sport. Sadly, in the last century, dozens of traditional ski cultures that viewed skiing as an essential utilitarian tool have faded and died without study. Each of these cultures had a unique style and method. In searching for remnants of traditional skiing in northern Eurasia, I have heard a similar refrain: “My father skied,” or “my grandfather skied” or “our people used to use skis.” Sadly, these mostly end with “but not anymore.”

Nils Larsen has been researching traditional skiing in the Altai Mountains since 2005. In his nine trips there he has produced an award-winning documentary (Skiing in the Shadow of Genghis Khan), led a National Geographic team (published in the December 2013 issue), written a number of articles, and assisted with the 2015 International Ski History Conference in Altay City, China. His research is ongoing.

Photo Caption: Archaeological researcher Wang Bo at the cave paintings near Altay City. The paintings depict skiers in motion (upper left) over hunted animals. A 2016 paper suggests the artwork may be 4,000 to 5,250 years old—ancient, but not as old as the 10,000-plus estimate used in the Altay Declaration.