A woman world champion and a man before his time.

By Edith Thys Morgan

Erik Schinegger leads the life of an Austrian world champion skier. The 68-year-old runs a thriving children’s ski school on Simonhöhe, one of the ski hills on which he learned to ski, in the farming community of Agsdorf. Off the beaten track from the celebrated ski areas in the Arlberg and Tyrol, people come to this area in the Carinthian Alps for quiet vacations, in winter to ski, and in summer to relax by the lake. Along with his wife Christa, Schinegger has welcomed them over the years at his two hotels and lakeside restaurant, and is every bit the local celebrity.

As much as his path—from humble farming roots and homemade barrel-stave skis to athletic greatness—resembles that of other Austrian champions, Schinegger’s story is unique.

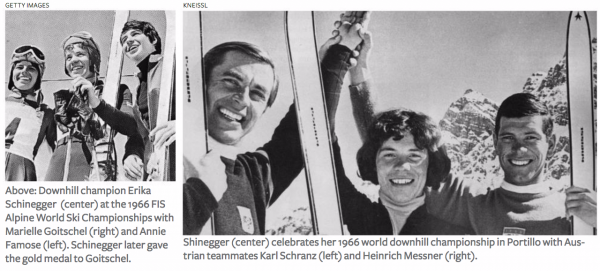

Schinegger’s winning downhill run at the 1966 World Alpine Ski Championships in Portillo was recently memorialized in a film celebrating the 50th anniversary of the event. That downhill title, however, is not listed on the Austrian Ski Team’s own list of achievements, and appears inconsistently in record books. Schinegger’s name populates Ski–DB.com, the comprehensive ski racing results database, but no longer appears on Wikipedia’s page of world ski champions. Instead, the 1966 title is attributed to France’s Marielle Goitschel. Where the name Schinegger does exist in the record books it is as Erika Schinegger, the woman he once was. (To see the Portillo film, go to http://www.skiportillo.com/en/blog/50-year-anniversary-of-portillo-world-champs/. The Schinegger footage begins at 6:16 minutes.)

I first heard of Erik Schinegger on the eve of my first World Championships competition in 1987. Our first stop, before getting credentials for the event, was for gender testing. We looked at our trainer, in equal parts horror and disbelief, and he assured us we would be keeping our clothes on. It would be a simple process of swabbing inside our cheeks for a saliva sample. But why? “Apparently there was an Erika who turned out to be an Erik,” he said. We had the test, and later chuckled that our official “Certificates of Femininity” might come in handy at Ladies Night, if there was ever any question.

Later that evening I asked Nick Howe, the journalist traveling with us, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of ski racing history, and he confirmed the barest of details about what the Austrian Ski Team referred to quietly, if at all. Erika had been a spirited and well-liked member of the Austrian ski team and in Portillo had won Austria’s only gold medal. In the run-up to the 1968 Olympics it was discovered, through the very same test I’d just had, that she had male chromosomes, and was thus disqualified from the Olympics. She underwent surgeries, and the transition from Erika to Erik apparently had been successful. Erik even attempted to compete on the World Cup as a man, but it didn’t work out. That synopsis left a lot of unanswered questions. A year after that conversation with Howe, in 1988, Schinegger explained much about his ordeal in his book, Mein Sieg Über Mich (My Victory Over Myself). It described in detail the remarkable journey from Erika to Erik, a triumph that was hard-won and painful.

Schinegger was born on the family farm in Agsdorf, to a mother who looked quizzically at the baby’s genital area and a father who would have preferred a male farm hand to a fourth daughter. The midwife congratulated the couple on their daughter, who grew up as an energetic tomboy. Despite her father’s disdain of athletics, Erika learned to ski by looking at pictures of Austrian greats and walked 14 kilometers to her first ski race at age 12. Starting dead last, in the 314th starting position, she won. She skyrocketed through the ranks first of the provincial and then the national team. In her first World Championships, in Portillo, 19-year-old Erika won the downhill gold.

Schinegger was born on the family farm in Agsdorf, to a mother who looked quizzically at the baby’s genital area and a father who would have preferred a male farm hand to a fourth daughter. The midwife congratulated the couple on their daughter, who grew up as an energetic tomboy. Despite her father’s disdain of athletics, Erika learned to ski by looking at pictures of Austrian greats and walked 14 kilometers to her first ski race at age 12. Starting dead last, in the 314th starting position, she won. She skyrocketed through the ranks first of the provincial and then the national team. In her first World Championships, in Portillo, 19-year-old Erika won the downhill gold.

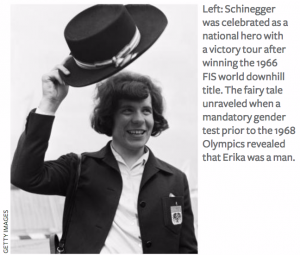

Austria embraced the fairytale, celebrating her with an extended nationwide victory tour. Agsdorf showered her with gifts and a hero’s welcome. Schinegger, who was earning success in technical events as well, seemed poised to make a run at her dream of winning three gold medals at the upcoming 1968 Olympics. For Kneissl, the Austrian Ski Team (ÖSV) and the people of Carinthia, Schinegger was a source of pride and economic opportunity.

In the fall of 1967 the fairy tale suddenly unraveled. In order to quell the suspicion that Eastern Bloc male athletes might be competing as women, the International Olympic Committee instituted gender testing for all female athletes prior to the 1968 Olympics. Schinegger and her teammates had the newly implemented saliva tests in Innsbruck as a routine part of their Olympic preparation. Later, while at a training camp in Cervinia, Schinegger was called back to Innsbruck. There she was greeted by a tribunal of six men—physicians and ski officials—who informed her that based on the results of the test she could no longer compete in the Olympics or on the ÖSV. They had prepared a statement for her to sign, announcing her retirement from sport for personal reasons, and strongly encouraged her to disappear—on a trip they would arrange—until it blew over. Bewildered and bereft, she signed the statement, but on the condition that she return to the clinic under an assumed name, for thorough testing. Two weeks later the results were conclusive and devastating, though in retrospect not entirely surprising. Erika was a biological man.

The urologist presented her with a choice: she could undergo plastic surgery and hormone therapy to continue life as a woman, thereby preserving her athletic career, the gold medal for Austria and the honor of her hometown. “Medicine can make you a woman,” he explained, “but never a real woman.” Alternatively, he continued, she could choose another, more painful option: She could have surgery to release the male sexual organs that had developed internally and become the man she was meant to be. Against the wishes of her parents, the ÖSV and her ski sponsor Kneissl, Schinegger—who had since puberty immersed herself in sport to bury doubts and fears about her sexuality—chose the latter.

The urologist presented her with a choice: she could undergo plastic surgery and hormone therapy to continue life as a woman, thereby preserving her athletic career, the gold medal for Austria and the honor of her hometown. “Medicine can make you a woman,” he explained, “but never a real woman.” Alternatively, he continued, she could choose another, more painful option: She could have surgery to release the male sexual organs that had developed internally and become the man she was meant to be. Against the wishes of her parents, the ÖSV and her ski sponsor Kneissl, Schinegger—who had since puberty immersed herself in sport to bury doubts and fears about her sexuality—chose the latter.

On January 2, 1968, Erika checked into the Innsbruck clinic under a false name, wearing women’s clothing. Over the next six months she endured four painful operations with no support or companionship. Words she uses to describe that time are loneliness, despair, confusion, depression, fear. She studied men’s ski technique on TV and a German etiquette guide to learn proper male behavior. On June 13, 1968, dressed in men’s clothing ordered from a catalog under a cousin’s name, Erik emerged. In a fast new Porsche, he drove away from the hospital and into an uncertain new life.

Within days, while competing for the first time as a man in a bike race, Erik revealed his transition at a press conference in Klagenfurt. The news stories were sympathetic, but the townspeople and the ÖSV were not. Adulation for Erika turned into embarrassment and shame about Erik. Villagers avoided him, and stared when he sat on the right side of the church—the male side—for the first time. The town of Agsdorf, which had given Erika a leather-bound document availing her of a two-acre plot of land on which to build a pension, reneged on it. The document read “Erika” not “Erik,” they reasoned, so it was no longer valid.

Of all the pain he endured, however, the worst was not being able to ski race. “It was through skiing that I felt love,” Schinegger explains simply. Only his former coach, Hans Gammon, welcomed him to an ÖSV camp, where the awkwardness with teammates was surmountable, but the hostility from the federation was not. Despite strong results against the likes of a young Franz Klammer, head coach Franz Hoppichler—under the directive of the federation—banned Schinegger, first from training camps and later from all opportunities to advance to the national team. Even after shining in time trials and winning three Europa Cup races, he was disallowed from the national team and blocked from competing for another country. Eventually, at age 21, Schinegger gave up the fight to race.

He passed his ski school certification in 1973 and took over the Simonhöhe ski school in 1975, the same year he married a pretty young woman named Renate. The couple had a daughter, Claire, in 1978. In 1988, he published his book and publicly gave his gold medal to Marielle Goitschel. In 1996, for the 30th anniversary of the event, Marielle was also awarded a gold medal by the FIS. She then returned Erik’s medal on a televised show in Paris. He had, it seemed, won his Sieg.

A more complete picture of Schinegger’s ordeal emerges in the 2005 documentary Erik(A), by Kurt Mayer. The film reveals the full extent of Erika’s and Erik’s struggles, through the lens of the people who shaped his story: the hometown boys who marveled at her determination, hard work and physical stamina; the mother who questioned the midwife from the start, but never rocked the boat of success (“you could see it always,” she says); the teammates who joked about her unfeminine hair and gait, and wondered why she never showered with them; the coaches who assumed her physique was a consequence of farm labor; and the medical and sport officials who contend that they denied Erika and Erik a future in skiing for her own protection.

While revisiting the people and places of her past, Schinegger shares her early doubts of her sexuality, and her fears of being a lesbian in a small Catholic town in a small Catholic country. She recalls her resolve to keep her secret hidden, even from herself, by immersing herself in the comfort of sport, the only place where she felt a sense of belonging. The most poignant meeting is between Schinegger and Olga Scarzettini-Pall, Erika’s closest friend on the team who won the 1968 gold medal that might have been Erika’s. Pall admits to being sad at losing her friend Erika—“We had a good time being girls”—and darkens when recalling the way the Austrian team took ski racing from Schinegger.

Fellow athletes, though claiming that they “knew it all along,” nevertheless did not dispute the medal or hold Erik responsible. “When I heard she would be able to have surgery and become a normal man, I was pleased for her,” says Nancy Greene Raine, to whom Schinegger was runner-up for the GS title in 1967.

“I blame the doctors and the ÖSV, not her,” says Marielle Goitschel, whose comment alludes to the question on many minds. How could the ski federation have failed to determine her true gender? Some, including Schinegger, suspect they chose to ignore it to protect the medal. Keeping Erika female was a matter of politics, economics and pride for the Austrian team. Karl Heinz Klee, then president of the ÖSV, maintains they were trying to protect Erika’s best interests by discouraging the “transformation,” which they feared would not be conclusive and would lead to a “miserable existence.” To him Erik quickly replies: “It was not a transformation. It was a correction.”

Erik(A) explores the complicated personal struggles, as Erik tried to prove his masculinity with a series of “crutches.” First was the Porsche, then his prowess with women. His first wife Renate recalls her husband as unsympathetic and overbearingly macho. His daughter Claire talks about growing up with the feeling that her existence was “living proof of his masculinity.”

Today, Schinegger’s journey is no longer a source of gossip and notoriety but a commentary on acceptance and understanding. Successive forms of gender verification—physical exams, then chromosome testing, then testosterone testing for “hyperandrogenism” —have been deemed humiliating, socially insensitive and ineffective, particularly in the case of athletes like Schinegger who are “intersex.” (Intersex is a general term used for a variety of conditions in which a person is born with a sexual anatomy that doesn’t fit the typical definitions of female or male.) The International Amateur Athletic Federation (IAAF) ceased all gender testing in 1992 and the International Olympic Committee followed suit by voting to discontinue the practice in 1999. Chromosome testing was last performed at the Atlanta Games in 1996. Gender is determined by a complete physical exam by each team doctor. The IAAF and IOC policies state that to “avoid discrimination, if not eligible for female competition the athlete should be eligible to compete in male competition.” Today, someone in Schinegger’s circumstances would be able to compete.

When Schinegger is brought into discussions on gender issues in sport, as with athletes like Jamaican sprinter Caster Semanya (who was allowed to compete at the Rio Games despite elevated levels of testosterone), he is encouraging but honest about enduring the experience. “It hurts but you get used to it,” Schinegger said in an interview before the Rio Games, adding his opinion that, “People should be able to decide for themselves whether they want to live as a man or a woman, once puberty has begun.”

With his second wife Christa, Schinegger has found “true warmth” and seems at peace with himself. Together they run their inns and in 2015 retired from their restaurant on the Urban See. His celebrity appearances include a 2014 stint on Austria’s Dancing with the Stars. He enjoys spending time with his three grandchildren, and proudly shepherds 3,000 plus kids each year through the Schischule Schinegger.

Life is good, and yet he still rankles at the treatment from the ÖSV. At the federation’s 100th anniversary celebration in 2008, the program omitted the year 1966 when listing World Championship medals. “They even didn’t mention the silver and bronze medals of Heidi Zimmermann and Karl Schranz,” says Schinegger, “just so they did not have to mention my name.” In 2016, when Austrian TV wanted to make a documentary about the 1966 World Championships, ÖSV president Peter Schröcksnagel prohibited it. The only apology Schinegger received was from the TV producers.

Life is good, and yet he still rankles at the treatment from the ÖSV. At the federation’s 100th anniversary celebration in 2008, the program omitted the year 1966 when listing World Championship medals. “They even didn’t mention the silver and bronze medals of Heidi Zimmermann and Karl Schranz,” says Schinegger, “just so they did not have to mention my name.” In 2016, when Austrian TV wanted to make a documentary about the 1966 World Championships, ÖSV president Peter Schröcksnagel prohibited it. The only apology Schinegger received was from the TV producers.

Schinegger’s story, however, continues to be told. A movie of his life—in the works ever since two Hollywood screenwriters read John Fry’s 2001 story on him in SKI magazine—will be completed this year. The German/Austrian co-production, directed by Reinhold Bilgeri, is being produced by Wolfgang Santner. “This story, of how he dared to do it, has never been told in a movie…and it needs to be told,” says Santner.

He is philosophical when taking stock of his celebrity appearances, his ski school, his popularity in France after handing the medal over to Goitschel, the 100,000 copies of his book that have sold, the documentary and the upcoming movie. “Had I been ‘fixed’ at birth I would not have had these opportunities,” he says, reinforcing what has become his life’s motto: Stein sind da, um sie wegzuraumen. Translated literally, the phrase means “rocks are there so we can remove them”—and challenges so we can overcome them.

Edith Thys Morgan is a former member of the U.S. Ski Team and frequent contributor to Skiing History. Read her blog at www.racerex.com and see “Foreign Relations,” her article on international ski racers competing for American colleges, on page 24.