At a recent conference in China, historians explored the ancient birth of skiing and how it spread across the continents. By SETH MASIA

As host of the 2022 Olympic Winter Games, China seeks a major presence in skiing. President Xi Jinping has proposed to invest $400 billion in new ski resorts, and to recruit 340 million winter sports enthusiasts before the 2022 Games begin in Beijing. If successful, that would be 25 percent of China’s population, generating about $100 billion in annual revenue. China would have the world’s largest ski industry.

China may be the future of the sport. The Chinese government also promotes the concept that its Altai Mountains are the origin point of skiing, some 8,000 to 12,000 years ago.

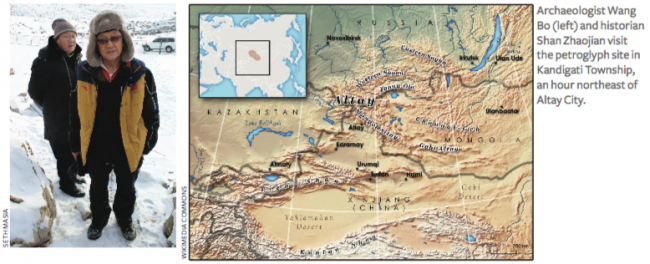

Regular readers of Skiing History are familiar with Nils Larsen’s film, Skiing in the Shadow of Genghis Khan, which received a 2009 ISHA Film Award, and his article “Origin Story” in the May-June 2017 issue. Larsen was among the first to introduce to the West the work of Shan Zhaojian, Wang Bo, Ayiken Jiashan and others, who have been tracing the history of today’s traditional Tuvan skiing culture back to prehistoric origins in the forested mountains of Central Asia.

In January, I attended the 2018 Ancient Skiing Academic Conference in Altay City, China. The conference focus was twofold: outlining recent research on the origins of skiing in Central Asia, and establishing cultural exchanges between the Tuvan hunting-ski culture and the Telemark tradition of skiing.

In January, I attended the 2018 Ancient Skiing Academic Conference in Altay City, China. The conference focus was twofold: outlining recent research on the origins of skiing in Central Asia, and establishing cultural exchanges between the Tuvan hunting-ski culture and the Telemark tradition of skiing.

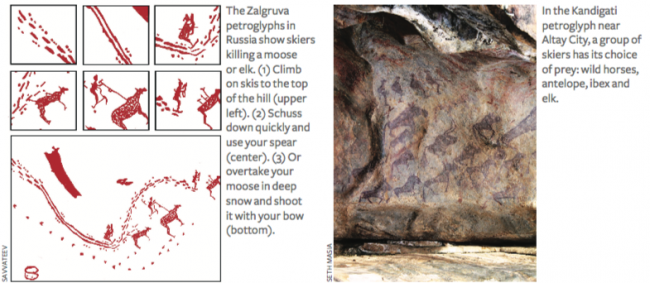

Recent work by archaeologists and anthropologists shows that rock art across the region, including much of southern Siberia, depicts hunters on snowshoes and skis, dating back as far as 7,000 years. Indirect evidence suggests hunters may have begun to use snowshoes and skis at the end of the last Ice Age, about 12,000 years ago. Knut Helskog of the University of Tromsø in Norway noted that human habitation goes back 40,000 years in northern Russia and 9,500 years in Scandinavia, with more than 300 petroglyph sites across the vast region—including at least 100 dating from the Stone Age. Helskog posits a natural progression from short wooden snowshoes to longer implements suitable for floating on deep snow. At some point the bearing surface grows big enough to allow gliding. Climbing skins are the next development. Meanwhile, the spear and bow serve as ski poles.

At Zalavruga in Russian Karelia, near the shore of the Arctic bay called the White Sea, a dramatic petroglyph shows skiers killing a moose or elk. We know the hunters are on skis, not snowshoes, because the artist(s) depict the tracks in the snow: tromping uphill with pole-marks alternating on both side of the track, and gliding downhill with pole plants widely spaced. The tactic depicted was to climb above the herd, then ski downhill at high speed to overtake the prey, half-buried in deep snow. In the Altay region, elk hunters on fur skis use the same technique today. According to Siberian rock-art specialist Elena Miklashevich of Kemerovo State University, the Zalavruga petroglyphs may be as old as 7,000 years (other experts suggest 5,500). In Southwest Siberia, along the Tom River, one petroglyph skier is depicted carrying what may be a lasso.

None of this should be surprising. As early as 1890, Fridtjof Nansen, in his book On Skis Across Greenland, cited linguistic evidence that skiing originated in Central Asia, along an arc between what is now Kazakhstan and Lake Baikal. This region includes the north slope of the Altai range. Nansen suggested that as skiing hunters followed herds of elk and reindeer, they spread northward and then east toward the Bering Strait and west along the coast of the Arctic Ocean, where ancestors of the Saami (Laplanders) brought skiing to Scandinavia around 5,000 years ago.

Since around 2005, this view of skiing’s origin has come to prevail among anthropologists, especially in view of the survival of a Stone Age skiing culture among the Mongol Tuvan tribe of the Altai mountains. The very existence of Tuvan skiing was broadcast to Western audiences by Nils Larsen’s 2008 film and Mark Jenkins’ National Geographic article in 2012. But Shan Zhaojian first posited the Altai as the birthplace of skiing back in 1993.

Modern Tuvans make their skis with hand tools, notably the adze. Today, of course, they use steel tools, but metal tools have been available since the Bronze Age, which began in this region about 5,000 years ago. Before that, the stone adze was an efficient tool for turning logs into smooth planks, and so we can easily visualize smooth-surfaced skis going back 10,000 or 12,000 years. Remember that the word “ski” originally meant a split of wood—a plank or board. When skiing is prime, we still reach for our powder boards.

China’s skiing Tuvans are careful to point out that they no longer kill elk—the entire mountain region is a designated conservation area. They will admit to catch-and-release hunting, dropping a lasso over the prey’s antlers, though that practice isn’t kosher either.

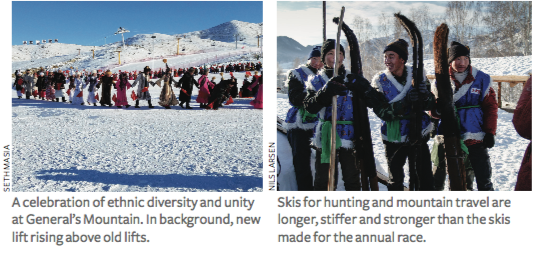

This skiing culture is said to have migrated into Xinjiang province about 400 years ago, from Tuva in southern Siberia. Since 2006 a ski race, first organized by Shan, has been one of many activities preserving the old culture. This year, more than 100 young men turned out for the race, run in two laps at the General’s Mountain ski resort outside Altay City. Each lap is about a mile: uphill, downhill, uphill and downhill again, with a total vertical of about 1,000 feet. The racers make their own skis—race skis are built for running, shorter and lighter than skis made for hunting. They’re covered with horsehide only on the bottoms, to save weight. The soft hair of cold-weather Altai horses glides much faster than Western-style climbing skins.

Also in attendance at the Altay conference was a delegation of about 20 Norwegians, comprising a telemark racing team led by Lars Ove Wangenstein Berge. With the collaboration of Andrew Clarke, chair of the FIS Telemark committee, and Shan’s group, the team is trying to get telemark racing included as a demonstration sport for the 2022 Beijing Olympics. Berge organized a parallel-GS telemark race at General’s Mountain, won by a couple of his teenage protégés. Berge and Shan would like to establish a torch relay from Morgedal, Norway—birthplace of modern skiing during the 19th century—to Altay City and on to Beijing for the 2022 opening ceremony.

The Chinese government fully supports the rapid development of alpine skiing as a healthy family sport. The country already boasts more than 100 small and medium-size lift-served ski areas. Altay’s Mayor Yu told me that local kids get free ski lessons and rental gear at General’s Mountain during school holidays, and estimates that 60 to 70 percent of the town’s population has tried skiing. The mountain has replaced its painfully slow old fixed-grip lifts with two new high-speed hybrid “chondolas,” one of which extends across the valley into new terrain to expand the resort by about 50 percent.

All of this skiing development is on government-owned land, with little or no delay for permitting or environmental studies. The central government does what it plans to do, without much feedback from local populations. Xinjiang province is home to half a dozen ethnic groups. The two largest—Turkic-speaking Muslim Uighurs, who consider themselves the original inhabitants, and Chinese-speaking Han Chinese, who dominate the government—have clashed in bloody riots as recently as 2014. To forestall ethnic conflict, all public gatherings are attended by riot police; government buildings, banks and hotels have barricades and tight security against real or imagined terrorists. It’s an odd cultural environment: a diverse population, free to travel around China and abroad, with a polyglot educated class well aware of news from around the world—all under an authoritarian regime led largely by engineers. Welcome to the Chinese century.

Seth Masia is president of the International Skiing History Association, and represented ISHA at the 2018 Ancient Skiing Academic Conference in China.