The North American Snowsports Journalists Association is celebrating 50 years.

By Phil Johnson

When the North American Snowsports Journalists Association (NASJA) gathers for its annual meeting in April 2013 at Mammoth Mountain, California, it will mark the 50th anniversary of the only coast-to-coast media organization dedicated to covering skiing and snowboarding.

The U.S. Ski Writers Association—now NASJA—was founded in 1963. The first meeting was held at the Jack Tar Hotel in San Francisco, and Carson White of the San Francisco Examiner was elected president. From that handful of journalists who gathered around an L-shaped table five decades ago came today’s NASJA, with 200 members from 31 states and two Canadian provinces.

In the beginning, almost every member was a newspaper writer, with early radio and television reporters, like Reno’s Snoshu Thompson, an exception. Today the membership is diverse: It includes traditional newspaper reporters and columnists, but also plenty of ph0to-journalists, broadcasters, authors, editors and Internet bloggers. As the definition of media has expanded in 50 years, so have the boundaries of ski coverage and NASJA membership. But the idea remains the same.

Organizations for ski writers had been operating in California and the Midwest since the 1950s, and in the fall of 1962, a group of writers met at the Eastern Slope Inn in North Conway, New Hampshire, to organize the Eastern Ski Writers Association. Europe had formed a ski writers’ association the previous year. So for groups across the United States with similar purpose, it made sense to consolidate into one—presumably greater, presumably grander—national organization.

Sounds simple, right? But as outlined in From Liftline to Byline, an informative history published by the Eastern Ski Writers Association in 2003, there were issues between the regions right from the start. For example: Who could join this organization? What were the standards of membership? And what about regional autonomy?

The East wanted a strong, formal set of standards, while a letter sent in March 1963 by a member from the Far West suggested something different in his realm. “We are a very informal organization with no rules, regulations, incorporation, constitution, or bylaws to hinder or help us,” he wrote. “Rather than be bound to strict conformity, we find that we operate best as we meet each situation and let policy be our guide.”

Compare that to the view expressed by newspaper writer Jay Hanlon of the Manchester, New Hampshire, Union Leader: “We tried to establish a group of professional ski reporters, weeding out the fringe writers. And in so far as national [goes], we tried to lift their standards to meet Eastern’s. We were a bunch of hard-nosed ski writers, not given to industry puff or presentation.”

Forming a national organization was turning out to be a difficult proposition. The first Eastern president, Mike Beatrice of the Boston Globe, went so far at first to recommend that his members not join.

A second U.S. Ski Writers Association meeting was held in Chicago in June 1964, but it was not until 1965 that all regions voted to affiliate with USSWA. What finally led to the agreement was a concession to the East that it could define its own standards, especially regarding membership eligibility, and that the national organization would be a “coordinating” group, with the regions as members, instead of individuals. Also behind the East’s willingness to join was the fear that if ESWA turned down the affiliation, the national group would simply solicit members in the East directly, which could create a competing group.

The ski industry welcomed the new organization. In requesting a listing of members, Eastern Ski Operators Association secretary William Norton wrote: “As you know, area operators are constantly confronted by persons looking for a free ride…It is our thought, if we had your membership list, we could separate the wheat from the chaff. At least we would know who your bona fide members are and could be better guided in our decisions to issue privileges to those who should have them, rather than some fly-by-nights who are only sponging.”

By 1965, the USSWA voted to organize into six regions: East, Central, Southern California, Northern California/Nevada, Rocky Mountain and Pacific Northwest. Journalists who wanted to be members of the national organization would have to join through their region, and voting on national matters would be accomplished by region, with the ballots weighted to reflect the percentage of the overall membership.

At first, the USSWA was primarily a writers group, featuring well-known journalists like Burt Sims of the Los Angeles Herald Examiner, Dana Gatlin of the Christian Science Monitor, Dave Knickerbocker of Newsday, Bill Keil of the Portland Journal, Ralph Thornton of the Minneapolis Star, Alex Katz of the Chicago Sun Times, Mike Madigan of the Rocky Mountain News, Luanne Pfeifer of the Santa Monica Evening Outlook, Henry Moore of the Boston Herald Traveler and Jerry Kenney of the New York Daily News. Influential print journalists like I. William Berry of the Long Island Press and Charlie Meyers of the Denver Post would join later.

But the organization was not just for representatives of major newspapers. Mike Strauss was already a well-known sports writer for the New York Times when he added ski writing to his reporting repertoire in the late 1950s. Given his affiliation—and his personality—Strauss didn’t need an organization to advance his writing efforts. But he realized that many of those who worked for small press outlets needed help to gain access to events and places. He led the way for acceptance of those from smaller publications to be equal members, so long as they met credentials requirements. “It put us all on a level playing field” he said.

While most members at first were print journalists, there were broadcasters, too. One of them, the widely known radio ski reporter Roxy Rothafel, became the central figure in a cause célèbre in the early 1970s. It seems that Killington president Preston Leete Smith objected to Rothafel’s description of the less-than-ideal conditions that he experienced at the mountain one day. Smith tried to blackball the ski reporter. Word got out and ESWA quickly came to Roxy’s defense, perhaps marking the only time ski writers have marched under the banner of the First Amendment.

By the end of its first decade, the USSWA had a constitution and bylaws. The organization also met annually and handed out awards. The first writing award went to Bill Berry of the Sacramento Bee, while the first Golden Quill award for contributions to the advancement of skiing went to Merritt Stiles of the U.S. Ski Association. In 1967, Olympic medalist Jimmie Heuga was the first Competitor of the Year.

Establishing common ground did not rule out controversy. This was a national organization, but the 3,000-mile-wide commitment sometimes seemed to require too much effort. In 1982, an Eastern delegation at the national meeting, believing that USSWA was on the verge of coming apart, voted against incumbent president Janet Nelson, a prominent writer and editor from the East who was seeking a second year in office. Instead, they backed Ben Rinaldo from Southern California, a former USSWA president, who, they would argue, was committed to maintaining the national organization. The apparent purge of Nelson infuriated some members. But USSWA survived: Its visibility grew, helped by a nationally broadcast news conference in 1984, and the membership increased during the decade, eventually growing to more than 300 full press members. The former associate membership category with a lower requirement for eligibility was eliminated in 1983.

One of the reasons for the organization’s growth was the increasing appeal of the annual meetings. In the early days, these were small events. By the 1980s they had become much larger, capped off by the gathering at Vermont’s Stratton Mountain in 1988 that is talked about still by those who attended. The event was organized by Craig Altschul, a past USSWA president who by then was Stratton’s PR chief. Multiple gifts were handed out to all who attended, and guests included the economist John Kenneth Galbraith, America’s Cup sailing champion Dennis Connor and the actress Jill Clayburgh. It was all capped off by a dinner dance on the final evening, featuring the popular band America, with a smoke and laser show to introduce the area’s new Starship gondola. Altschul arranged rental tuxedos for all the men who attended.

By this time, members from Canada had formed their own chapter. The name U.S. Ski Writers Association no longer seemed appropriate, so in 1989, it was changed to the North American Ski Journalists Association. Two years later it was changed again. Some members were concerned that keeping “Ski” in the name would send the wrong message to younger writers who worked with snowboarders. So the current North American Snowsports Journalists Association was born … and the acronym NASJA, created two years earlier, did not have to be changed. Several years later, the Canadian region collapsed. It seems their members found a cross-nation organization unwieldy, preferring instead to merge on an East, Central, West basis across borders. But the new name remained.

Despite attractive annual meetings, a timely annual membership directory, and a growing awards program that now also recognized excellence in photography, broadcasting and book publishing, there remained undercurrents of unhappiness at the regional levels. With weighted voting, the East, because of the size of its membership, could veto initiatives popular with the other regions. And Eastern delegates were often blunt in making that point.

To address this and other general concerns, in 1995 NASJA president John Hamilton, a well-known San Francisco-based broadcaster, organized a session at Snowbird, Utah, at which representatives of all the regions sat down in one room to talk out issues facing the organization. Philadelphia attorney and mediator Ed Blumstein, who as a freelance ski columnist was also a member of the organization, directed the daylong session. It was classic mediation: Discussion groups were mixed and all options, including dissolving the organization, were on the table. But as people began to discuss their needs and interests, it turned out everyone had the same goals, recalls Blumstein. “We just had to figure out how to do it.”

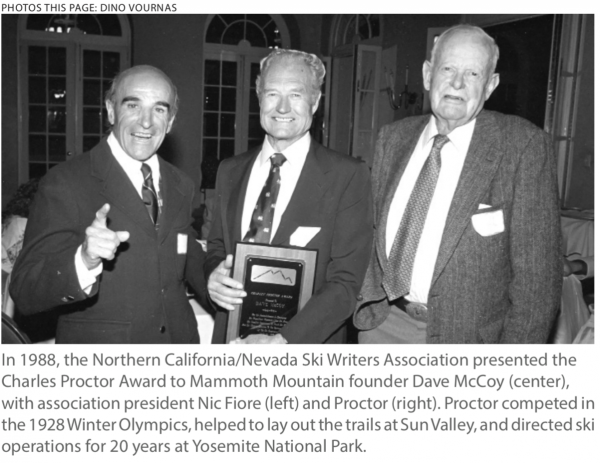

In addition to a newly discovered appreciation among regions, the major thing to come out of that meeting was a decision shortly thereafter by the four regions in the West to consolidate. The four (Rocky Mountain, Southern California, Northern California/Nevada and Pacific Northwest) individually had small memberships and there was some feeling that a merged West Region would create a more level playing field at National meetings. “And we were running out of volunteers to lead the organizations,” recalls John Naye, a long time West and NASJA leader. While it did streamline the organization, some distinctly regional activities, like the Charlie Proctor Annual Awards dinner in San Francisco, and the Rocky Mountain Trade Fair in Denver, fell by the wayside.

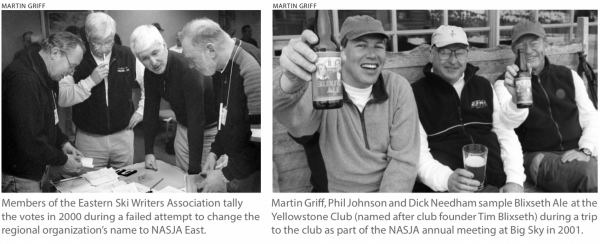

The Midwest voted to remain independent. That left NASJA with the three regions it has today: NASJA West, NASJA Midwest, and the Eastern Ski Writers Association. Two votes have been held in the region to change the ESWA name to NASJA East but both have failed to get a required 60 percent.

While the behind-the-scenes politics and maneuvering continued, NASJA president Dave Irons, a long time writer/broadcaster from Maine, seemed to put a punctuation mark on the “them versus us” issue in 2000, declaring, “we are them, and they are us.”

Over the years, ethics occasionally came up. What was the relationship between the journalist and the industry? There were instances reported when a writer’s plans for the weekend were based on who was offering the best deal; or a request was made to host six people in return for a story; or a new pair of skis was delivered to a newsroom.

Sometimes a PR person was forced to make a quick decision. One well-known PR director recalls being asked to give up his seat at dinner to babysit the son of a well-known writer. The PR guy and his wife ate pizza in their room with the child that evening.

In the mid-1980s the organization, acting on recommendations by a committee headed by the late Bob Gillen, who had been both a ski journalist and a ski area marketing director, adopted a more formal set of ethics standards. As those were developed and still stand, no member of the organization shall attempt “to seek special considerations or courtesies from any segment of the snowsports industry in exchange for a favorable comment or review.”

Once primarily comprising full-time newspaper writers, the group now reflects the people who produce most ski copy today: freelancers, many of whom initially joined to establish legitimacy. While once most of the writers covered competitions, members today are much more likely to focus on ski areas and travel. While the early members were almost all male, a significant number of women are now involved.

That membership is growing older. Ski journalists don’t retire, it seems. Craig Altschul, the former USSWA president, proposed at one time that all members over a certain age step aside, and—perhaps jokingly, perhaps not—he also suggested that the ski industry provide some kind of a ski pass incentive to send them on their way.

Probably the biggest challenge to the organization is the emergence of the Internet and social media. With the ability to update everyone about everything as often as you want, many journalists don’t look to an organization to stay in touch. The industry also relies less on organizations. Where the NASJA credential was once the prime way to be certain a journalist was genuine, online checking can be a quicker and more comprehensive method of validation.

As the North American Snowsports Journalism Association enters its second half-century, it seems to have reached a maturity level where issues between regions no longer dominate the discussion. The challenge today is to attract new, younger members who not only have the talent to be successful but also want to sustain an organization that appeals to others with the same goals. As has been the case from the start, NASJA still is the only organization organized exclusively for those who cover the sliding sports.

Author Phil Johnson is the current president of NASJA.