SKIING HISTORY

Editor Kathleen James

Art Director Edna Baker

Contributing Editor Greg Ditrinco

ISHA Website Editor Seth Masia

Editorial Board

John Fry, Seth Masia, John Allen, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

John Fry, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Chan Morgan, Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Christin Cooper, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, Chris Diamond, Mike Hundert, David Ingemie, Rick Moulton, Wilbur Rice, Charles Sanders, Bob Soden (Canada), Betty Tung

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Business & Events Manager

Kathe Dillmann

P.O. Box 1064

Manchester Center VT 05255

(802) 362-1667

kathe@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History or skiinghistory.org, either in full or in part.

Short Turns: FIS boss Kasper steps down

Top exec will step down after five decades at the sport’s governing body.

Gian Franco Kasper, the president of the International Ski Federation (FIS), recently announced that he will step down this spring after 22 years at the helm of the sport’s governing organization. Both an effective and controversial executive, Kasper has held different roles at FIS for nearly 50 years.

Photo at top of page: An effective and controversial leader, Kasper’s reign has been spiked with controversy, often fueled by his off-hand remarks. DPA Picture Alliance / Alamy Stock Photo

Kasper, 75, was named secretary general of the federation in 1975 and took over as president in 1998. He succeeded the late Marc Hodler, who at 80 had headed FIS for nearly 50 years, the longest reign at any international sports organization. Under Hodler, the season-long World Cup competitions and freestyle were introduced, snowboarding competition came under FIS governance, and he exposed the bid-rigging scandal of the 2002 Winter Olympics.

Under Kasper’s reign, the number of ski and snowboarding medaling sports at the Winter Olympic Games has multiplied to more than 50, with many new freestyle events successfully geared to attracting a younger audience.

The FIS began in 1924 as a Scandinavia-based and operated organization. The first two presidents were a Swede and a Norwegian. With Hodler’s election in 1951, the FIS moved its headquarters to Switzerland, where they have remained for almost 70 years. The current headquarters are in Oberhofen, where the influential Marc Hodler Foundation is also located.

Regarding Kasper’s succession, the FIS says that it supports “a timely process for the national ski associations to prepare any applications for candidacies.” The less-than-transparent Hodler-Kasper succession process in 1998 was harshly criticized by former FIS vice-president Bjorn Kjellstrom. The betting now is on another Swiss, Urs Lehmann, 1993 world championships downhill gold medalist, President of the Swiss Ski Federation, a successful business consultant, President of the Laureus Foundation, and husband of Swiss acrobatic ski champion Conny Kissling.

Kasper’s long tenure also has been spiked with ongoing controversy, occasionally fueled by his off-hand remarks. Last year he caused worldwide headlines and brief outrage when in an interview with a Swiss journalist he sarcastically remarked that with authoritarian governments it was easier to overcome environmental obstacles to Olympic site selection. He previously found himself under the spotlight in 2005 after commenting about women ski jumpers that the physical force upon landing “seems not to be appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view.” The FIS did eventually sanction women’s ski jumping, which made its Olympic debut at the 2014 Sochi Winter Games.

This season, Kasper scrapped with athletes and coaches who criticized the expanded 2019-20 alpine schedule for not providing enough time for travel and proper recuperation. Kasper conceded that the alpine World Cup circuit contains “too many races,” and then offered not much more than sympathy.

“I know it’s not easy for the athletes and also for some organizers. We are now at a certain limit, there is no question,” Kasper said at a press event in October. “But FIS is not here to prevent races but to organize races.” He did say that the FIS would look into improving its scheduling process. Without Olympic Games or World Championships this season, the current alpine World Cup schedule runs nonstop from October through March, with 44 men’s events and 41 women’s events at nearly two dozen venues.

Kasper, a former journalist, also has held leadership roles with the International Olympic Committee and the World Anti-Doping Agency, among others. He was elected to another four-year term as FIS President in 2018, but will only make it halfway through. He will officially resign his post at the next FIS Congress in Thailand in May. --Greg Ditrinco

Wear Your Passion on Your Sleeve

Karl Johan grew up with an immutable ski uniform: a Demetre sweater. It made sense. He lived in Seattle, near Demetre’s Ballard-based factory. And his family all wore the sweaters whenever they skied. As did most Seattle-based skiers.

The factory and the brand have since shut down (Roffe purchased Demetre in 1987, and itself closed a decade later), but the sweaters still live on in Johan’s memories and closet in Sun Valley.

Marketing director for Sun Valley Culinary Institute, Johan has long collected the sweaters at garage sales, thrift stores, retro clothing stores, online—wherever he can find them. When he nabs one, he cleans it, steams it, and stashes it away. His collection can number more than 50 sweaters at a time. That number decreases whenever he holds a pop-up vintage sweater sale in Sun Valley.

Johan notes that the old-school sweaters hold up remarkably. “The designs and colors are amazing,” he says. And “they look brand new” whenever he still sees them on the slopes. He also enjoys the local angle to his soft-goods obsession, as John and Sally Demetre have long had a home in Sun Valley.

Demetre was founded in 1921 by John’s father as the Standard Knitting Company, which manufactured uniform sweaters out of its factory in Ballard, Washington, which is now a hip waterfront neighborhood of Seattle. During the time Demetre sweaters were being manufactured, Seattle was one of the largest apparel centers in the country and considered a pioneer in outerwear.

In the early 1960s, Demetre saw a business opportunity in the explosive growth of skiing, and expanded into ski sweaters. The company landed early sponsorships with the U.S. and Canadian Olympic ski teams. The U.S. Ski Team wore Demetre sweaters at the 1972 Winter Olympics in Sapporo, Japan. During its heyday, Demetre was tagged “America’s first name in fine ski sweaters,” with an ad from a 1972 issue of Skiing magazine pledging: “One look and you know it’s Demetre.”

As any skier of a certain age can confirm, Demetre sweaters were colorful, comfortable, and tightly woven to provide superior warmth. The construction resulted in a heavy-weight sweater that was virtually indestructible. Not surprisingly, many of the sweaters have survived, now 50 or so years later. And many Demetre fans have kept their favorite sweaters.

Pinterest, Ebay and other websites are full of Demetre sweaters—and memories from skiing’s golden era. One fan blissfully noted of her Demetre sweaters, “I wore them when I was skinny.” —Greg Ditrinco

Buck Hill Marks 50 With Sailer

In December 2019, Buck Hill—a small Minnesota ski area with a big racing reputation—celebrated 50 years with its legendary coach, Erich Sailer. Since founding the racing team back in 1969, Sailer has churned out an impressive roster of Olympic and World Cup athletes, including Kristina Koznick, David Chodounsky, Tasha Nelson and Lindsey Vonn. Vonn retired in 2019 with four World Cup overall titles, 11 Olympic and FIS World Championship medals, and 82 World Cup victories—a record for women, and just shy of Ingemar Stenmark’s record-setting 86 wins.

Thanks to Sailer, Buck Hill is home to one of the country’s most active recreational racing programs, drawing youth and adults from the Twin City suburbs for training, leagues and competitions. An honored member of the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame, the Austrian-born coach pioneered summer ski racing in the United States in 1956 with a camp at Timberline on Oregon’s Mount Hood. By 1967, his camp near Red Lodge, Montana had become the biggest in the country.

Buck Hill was founded in 1954 by Charles “Chuck” Stone Jr. and his future wife, Nancy Campbell. In late 2019, Nancy published Buck Hill: A History. To purchase a copy, email ncstone@aol.com. —Kathleen James

Snapshots in Time

1866 SONDRE NORHEIM’S HEEL

In 1733, a Norwegian military officer, Col. Jens Henrik, wrote the first ski instructions for the military. Those rules contain the first mention of heel bindings, but illustrations of military skiers throughout the 18th century show only toe straps. Despite the increased pressure of jumping and racing competition, begun in 1765 and 1767 respectively, the heel binding didn’t really catch on until Sondre Norheim’s dramatic exhibition at Mordegal a century later. “With legs drawn up, he flew like a bird.” Thus 41-year-old Norheim impressed the crowd at an 1866 jump at Hoydalsmo, near Mordegal in Telemark. Within two years, the Telemark skis—cambered at the waist, broadened at the tip—and Norheim’s new heel bindings astonished the crowd at Christiana. Sport skiing was on its way. —Ted Bays (Nine Thousand Years of Skis: Norwegian Wood to French Plastic)

1936 SISSIES, SPOILSPORTS AND MOTHER-FRIGHTENERS

The first death on the slopes shook up the small skiing fraternity of the day. An emergency meeting was called by the New York Amateur Ski Club, whose founder, Roland Palmedo, appointed Minot “Minnie” Dole chair of a committee to inquire into the causes and handling of ski accidents. The results of their questionnaires was disappointing. Only a hundred replies dribbled in. Of these, roughly half accused the committee of being “sissies, spoilsports, and frighteners of mothers.” —Gretchen Rous Besser, “Samaritans of the Snow” (Collected Papers of the International Ski History Congress, 2002

1959 LISTEN AND LEARN

Have you reached a plateau in your skiing where nothing seems to help you improve? Then “Skiing by Ear Method” may be just what you need! Relax and learn with these 33-1/3 rpm records. $8.95 each. Money-back guarantee! —Advertisement in SKI “Holiday Gift Guide” (December 1959)

1967 WORLD CUP ACCOLADES

The winter of 1967 marked the beginning of a new era in international ski racing. For the first time in the history of the sport, the world’s best racers were rated not on the basis of one or two headline races, but on a systematic accumulation of results over the whole season. The new system proved a smashing success. So much so that the World Cup of Alpine Skiing is to become a permanent annual fixture of the sport, rivaling the Olympics and the FIS World Championships. Initially ignored by international ski officialdom, the World Cup won instant and enthusiastic acceptance by the two groups most important to the success of ski racing: the racers themselves and the press, who report the results to an eager public. —John Fry (SKI, September 1967)

1978 THE BUCK STOPS HERE

Your three-miles-a-day skier is starting to see the wisdom of the East. For the first time, Stratton (Vermont) is drawing vacationing skiers from Washington DC, Texas, Georgia and Puerto Rico. And these are not weekend skiers. “Vail, founded the same year we were, programmed itself as a vacation resort from the beginning,” says Stratton marketing manager Jeff Dickson. “It worked closely with airlines and travel agents and ski clubs to get people to come for a week. The Eastern resorts are waking up. The only way we can support the lifts we’re building is by becoming a vacation destination.” —Morten Lund (SKI, September 1978)

1989 CLAMORING FOR THE BEST

A great perplexity hits me every time I hear skiers talking about lift ticket prices. Late last season, I skied Butternut Basin in the Berkshires. The change from eight years earlier was dramatic: lifts, lodges, trails, parking and food were greatly expanded. And instead of narrow ribbons of icy snow or rock-hard moguls, the trails were white velvet from edge to edge. As good as Colorado. What happened? Butternut has been transformed into the New Skiing, with trail systems that disperse skiers around the hill, massive snowmaking, and squads of grooming machines that work every trail by sunrise into a soft-but-firm surface that spells, “Have a ball.” Yet skiers are having a fit—those lousy lift ticket prices keep rising. —Morten Lund (Snow Country, January 1989)

2000 HIGHER POWER OF POWDER

In the 2000–2001 season, I didn’t finish 13 of the 24 races I entered. I’ve seen people lose their hair or get religion over less. But I knew I was getting better; I knew I had far more control than ever before. It just wasn’t always obvious to everyone else. And explaining myself all the time got old fast. Better to be laconic—the shrug, the smirk. People hear what they want to, anyway. … When fans or young racers ask me the Big Question, I tell them: “Go fast.” It’s the whole deal, the only tip worth taking. —Two-time overall World Cup champion and 11-time Olympic and FIS World Championship medalist Bode Miller (Bode: Go Fast, Be Good, Have Fun)

SKI LIFE

from SNOW COUNTRY / DECEMBER 1988

That’s not what I said; I said “We have six inches of powder under an ice crust.”

Why's It Called That? Mont Tremblant

The Algonquin believed that Quebec’s Mont Tremblant trembled when violated by human exploitation.

The mountain lay in the heart of Weskarini Algonquin territory, and was the home of the Great God, or Manitou. They called it Manitou Ewitchi Saga, the mountain of the great god, or Manitonga Soutana, mountain home of the spirits. In 1652, Weskarini were massacred here by invading Iroquois. Many sought refuge with French Jesuits, and were forced to convert to Catholicism.

The mountain lay in the heart of Weskarini Algonquin territory, and was the home of the Great God, or Manitou. They called it Manitou Ewitchi Saga, the mountain of the great god, or Manitonga Soutana, mountain home of the spirits. In 1652, Weskarini were massacred here by invading Iroquois. Many sought refuge with French Jesuits, and were forced to convert to Catholicism.

The Weskarini believed the mountain trembled when violated by human exploitation. And so the French settlers adopted the name Mont Tremblant (“Trembling” in English). What the Weskarini meant by “trembling” is unclear; one folk-tale recounts violent storms destroying swathes of forest. Seismic activity is common. Several faults run within 50 miles of the mountain and the region has recorded at least one magnitude 6.9 earthquake in the past 250 years, and a couple of 4.5 quakes right in Ste-Agathe during the past 25 years. It’s possible that the Weskarini actually felt the mountain shake. —Seth Masia

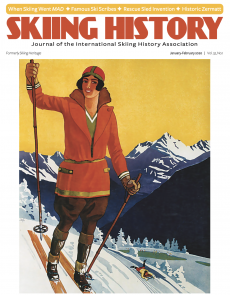

Ski Art: Gunnar Hallström (1875–1943)

On the one hand Gunnar Hallström, Swedish painter of national-romantic scenes, was everything a modern environmentalist might honor. He settled on the island of Björko in Lake Malar, about an hour by boat out of Stockholm, and became involved in the preservation of Birka, Sweden’s oldest town, and in the maintenance of the island’s traditional farms. He persuaded the government to buy up the land and put it under protection. Today it is managed by the Riksantikvarieämbetet, the National Heritage Board.

On the one hand Gunnar Hallström, Swedish painter of national-romantic scenes, was everything a modern environmentalist might honor. He settled on the island of Björko in Lake Malar, about an hour by boat out of Stockholm, and became involved in the preservation of Birka, Sweden’s oldest town, and in the maintenance of the island’s traditional farms. He persuaded the government to buy up the land and put it under protection. Today it is managed by the Riksantikvarieämbetet, the National Heritage Board.

But there is another side to Hallström’s art, first coming to notice in the early years of the 20th century. The frontispiece of Henry Hoek and E. C. Richardson’s 1907 Der Skilauf und seine sportliche Benutzung (Skiing and its Sporting Use) is a reproduction of Hallström’s skier. The original is believed to have been owned by a Munich publishing firm that later had connections with the Nazis. When the Germans were in deep financial trouble following World War I, communities printed their own money, called Notgeld. The town of Furtwangen put Hallström’s Schneeschuhläufer (Ski Runner) on its 10-mark note. That gained him a great deal of attention. In 1921, for example, the German Ski Association’s journal Der Winter called Hallström “well known.”

In the political turmoil of the 1920s and 1930s, Hallström moved to the right in Sweden and became involved in decorating with swastikas one of the lodges to which Hermann Göring fled after the failed 1923 Hitler putsch. He signed his initials in the spaces created by the squared swastika symbol, and he appears to have been involved with the pro-Nazi Swedish Carlberg circle.

Politics aside, the painting illustrated here, used both as the frontispiece to Hoek’s and Richardson’s book and as the formidable image on Furtwangen’s 10-mark note of December 1, 1918 proves his knowledge of skiing as well as his expertise in landscape depiction. —E. John B. Allen

After World War I, a German town used Hallström’s image of a skier on its 10-mark note. He was likely involved with pro-Nazi circles in Sweden. --E. John B. Allen

This article first ran in the January-February issue of Skiing History.

Table of Contents

2020 Corporate Sponsors

World Championship

($3,000 and up)

Alyeska Resort

Gorsuch

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Obermeyer

Polartec

Warren and Laurie Miller

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

World Cup ($1,000)

Active Interest Media | SKI & Skiing

Aspen Skiing Company

BEWI Productions

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Country Ski & Sport

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Descente North America

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Fera International

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association (NSAA)

Outdoor Retailer

POWDR Adventure Lifestyle Corp.

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply, Inc.

Gold ($700)

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

Silver ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Clic Goggles

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Hertel Ski Wax

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

NILS, Inc.

Portland Woolen Mills

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snow Time, Inc.

Sports Specialists, LTD

SympaTex

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge & Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Vuarnet

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

For information, contact: Peter Kirkpatrick | 541.944.3095 | peterk10950@gmail.com

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!