SKIING HISTORY

Editor Kathleen James

Art Director Edna Baker

Contributing Editor Greg Ditrinco

ISHA Website Editor Seth Masia

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Chan Morgan, Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Christin Cooper, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, Chris Diamond, David Ingemie, Rick Moulton, Wilbur Rice, Charles Sanders, Bob Soden (Canada)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Business & Events Manager

Kathe Dillmann

P.O. Box 1064

Manchester Center VT 05255

(802) 362-1667

kathe@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Big Air

Alpine ski jumpers—sticking Geländesprungs, cliff hucks and gap-jumps—have been sending it for more than a hundred years.

Jesper Tjader explains what he wants to try on a practice run for the 2014 Nine Knights terrain park competition in Livigno, Italy, and no one thinks it’s possible. But he casually skis onto the in-run anyway. He’s planning a transfer from one big ramp to another one about 50 meters (164 feet) away on a completely different course. Coming up short means a face-full of vertical ice and almost certain serious injury. Overshooting isn’t a consideration since nobody believes he’ll clear the massive gap to begin with. But 20-year old Tjader, without consciously knowing it, is riding a wave of Big Air heroics that will define the first two decades of alpine ski jumping in the 2000s. The Swede sticks the landing three times that day on a jump no one else is even thinking about, and the last time he throws a double back flip.

Photo above: Athletic achievements in action sports often arrive unplanned. Swedish freeskier Jesper Tjader decided to try an unprecedented 50-meter “death gap” transfer between ramps during practice at a 2014 competition. He nailed it three times. And on his final attempt, he threw in a double back flip. Suzuki Nine Knights photo.

When Skiing Big Air debuts at the 2022 Winter Olympics in China, it will be on the back of these kinds of attention-grabbing feats over the past twenty years. Candide Thovex making the first successful jump on 120-foot Chad’s Gap, near Alta, in 1999. Jamie Pierre dropping a 255-foot cliff huck in 2006 in the Grand Targhee, Wyoming, backcountry, only to have Fred Syversen up the ante to a bonkers, and accidental, 351 feet two years later filming in Norway. Rolf Wilson laid down a 374-foot-long alpine jump in 2011 during a competition off the 90-meter jump at Howelsen Hill, and David Wise popped 46 feet above a park jump in 2016 in Italy, upping the record by more than 10 feet. All of this was accomplished on regular alpine ski gear—and it all began with something called the Geländesprung.

Hannes Schneider likely introduced, or at least popularized, the Geländesprung (literally “terrain jump” in German) in the early 1900s in the Austrian Arlberg. Writing in Skiing magazine in 1964, G.S. Bush mentioned Schneider demonstrating a maneuver where he “used two ski poles instead of one, and, an accomplished jumper, he leaped even when there was no ramp. Rushing across a sharp break in a slope, he’d push himself up and forward on the poles, catapulting himself high over the hill’s edge, and then, by twisting his body and skis, he’d change the direction his skis were facing in mid-flight. He called this spectacular trick, ‘Geländesprung.’”

By the 1950s that description was obsolete and gelandes had come to more broadly encompass all alpine-style jumping that includes ski poles and bindings with locked-down heels—two major things that differentiated it from classic heads-and-tips-first Nordic jumping. It began to make regularly noted appearances in the U.S. in the 1930s where it was mentioned as an activity at areas from Glen Ellen, Vermont, to Badger Pass in Yosemite.

Oddly, it also turned up on an American stamp issued in 1932, commemorating that year’s third Winter Olympics, being held in Lake Placid. As noted collector James Riddell remarked in an article, “The Scandinavian disciplines Langlauf and Springlauf only at Lake Placid! This stamp, strangely enough, depicted a Geländesprung, which hardly suited either event.” Ski journalist Mort Lund observed that the stamp displayed “a form of skiing for which there was no Olympic, world or local competitions…” It may have been the 1940s before the first known gelande events started occurring at places like Alta, Utah.

Seeing is Believing

What would primarily propel alpine jumping is photography, which has proven both a blessing and a curse, with detractors claiming that photo fame and peer pressure drive kids to do dangerously crazy things they wouldn’t otherwise. But as the world rolled into the 1960s, magazine photos and movies became major drivers for alpine ski jumping. Not because people were doing it for the cameras, but because the cameras craved it. Big air was dramatic and it sold. Take Jim McConkey, for instance.

A famous early image showed him jumping 100 feet over a ski plane on a glacier in Canada in 1962. He next dropped a 90-foot cliff in the Bugaboos, which was then nearly unthinkable. Ninety feet is still bragging material. And it opened up the mountains to stuff so ridiculous that jumpers had to create wings. Tragically, one who did was McConkey’s son Shane, who died in a skiing and BASE-jumping accident in the Dolomites in 2009.

Jim McConkey’s early 1960s plane-jumping image was followed by a 1963 Hans Truöl photo of legendary Austrian racer Egon Zimmermann, who would go on to win the Olympic downhill gold medal, jumping the Flexenpass highway above Lech and clearing a new 356 Porsche in the process. Zimmermann personally gave visitors a postcard of the photo at his Hotel Kristberg in Lech right up until his death at 80 this past August. He once told me that he’d done the jump mainly as a promo for Porsche, which he thought was ironic since he suffered a bad wreck in his own Porsche several years later. The pic is still iconic today and along with McConkey’s plane jump helped create the modern concept of gap-jumping as an Evel Knievel form of showmanship.

The value of film to big league ski jumping was cemented when skiing action scenes, being shot by Willy Bogner in some of the Alps’ most glamorous locales, began appearing in James Bond movies. The high-octane Bond footage gave a big boost to skiing in general and extreme jumping in particular, the latter as a result of three deeply memorable stunt sequences.

The first was in On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in 1969, where George Lazenby’s stunt skiers were German racer Ludwig Leitner and Swiss downhill ace Bernhard Russi. Near the end of a long chase sequence at Murren, Switzerland, Bond jumps over a highway very reminiscent of Zimmermann’s Porsche-clearing gelande. Only Bond did it over a huge snowplow with a snowblower that devours the pursuing bad guy when he doesn’t go big enough. Unfortunately, “Russi was injured when he crashed on the road,” Willy Bogner once told me. But it definitely raised the stakes on gap-jumping and built on the Zimmermann/McConkey foundation.

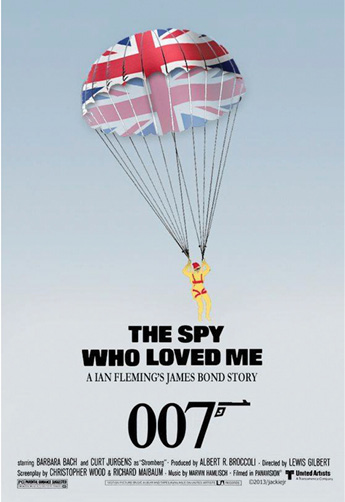

Next came Rick Sylvester’s mind-boggling jump off Mount Asgard on Baffin Island in 1977’s The Spy Who Loved Me that ended 3,000 vertical feet later with a parachute landing. It was a game-changer that furthered the blending of skiing with BASE-jumping and fired up ski jumpers by exponentially extending the limits of what was possible. The movie scene took three tries for the camera crew to get the shots, but it awed a global audience and inspired people like Shane McConkey. (Sylvester got the coveted call for the Spy stunt because he had skied off El Capitan in California in 1972, which was filmed by a young Mike Marvin, who went on to Hot Dog—the Movie fame. Sylvester’s El Cap feat is considered the first filmed BASE jump on skis.)

In 1981’s For Your Eyes Only, extensive ski scenes in Cortina, Italy, are capped by former 6-time World Champion freestyle skier John Eaves standing in for Roger Moore and jumping off Cortina’s famed 90-meter Nordic hill—on a pair of 205 Olin Mark VI slalom skis. Almost everyone used at least 215s on gelande jumps a lot smaller than a 90-meter, with 220s more likely under foot. Plus Eaves did it tandem, side-by-side with a regular, properly equipped Nordic jumper.

“I had my own jump,” Eaves told me. “It was set at 0 degrees. The Nordic take off was -11 degrees. They need that to get into the air foil. Mine felt like a good kick when I hit it, allowing me to gain altitude over the Nordic jumper immediately. Then I would slowly lose altitude as he went ahead… I did 200 feet once.” It wasn’t out of his wheelhouse, Eaves explained. “I got second place at the Whistler gelande in 1974 on a pair of Dave Murray’s lead weighted downhill skis.”

Big Air, Big Competitions

Competitive alpine ski jumping wasn’t hugely successful over the years, but it was the testing grounds for a lot of what followed. While earlier gelande competitions definitely occurred, Alf Engen staged the first-ever National Gelande Championships at Alta in 1964, and just for good measure won it.

That event lasted for ten years (plus occasional resurrections for anniversaries) before insurance companies and lawyers got involved. But by then there were gelande comps, and their direct descendants in the form of “ski splashes,” going on everywhere: Mad River, Sugarbush, Purgatory’s famous Goliath Gelande, Snowbowl Montana, Steamboat Spring’s Winter Carnival off the 70 and 90-meter jumps. Other hosts included Jackson, Whistler, Alyeska, Aspen’s Winterskol, a swimming pool alongside the Silvertree Hotel in Snowmass, and so on, with a tour that included 13 stops at its peak. But Alta’s remained the granddaddy and the big one everybody aimed for.

Interestingly, Porsche stayed allied with alpine ski jumping over the years, supplying a car as first prize for one of the early gelande events in Vail, won by Mark Jones in 1974 at the then world-record distance of 213.5 feet. The prize got everyone’s attention as much as the length, and helped to jump-start (ahem) the gelande tour.

By this time freestyle skiing aerial events had been going on for a few years in the US and around the world. They were formally recognized by the FIS in 1979 and first showcased at the Olympics in 1994. Combining outrageously vertical air (20 feet above the kicker, up to 60 feet above the landing) with full-on gymnastics (three full back flips with five full twists for example), they’ve made for great TV. They also led directly to the jibbing movement and park and pipe riding that rewards tricks as much as amplitude or distance.

For the last 40 years, the sky has literally been the limit for gelandes, gap-jumps and cliff hucks, to the point where some of it has gone almost beyond the pale and stalled a bit as a result. Meanwhile, park and pipe events have combined most of the other forms of alpine jumping and added some new wrinkles, along with wide exposure and money that both attracts and nurtures a lot of the jumping talent.

Freestyle courses, super-pipes and big air kickers provide highly visible venues for people to go huge while emphasizing tricks and still being able to ski away. That’s because the jumps are vaguely within reason, and are regular events instead of one-off stunts to set a record.

Video Revolution

There’s no avoiding the inherent danger of big air. After Paul Ruff’s fatal 160-foot jump in 1993 near Kirkwood, California, in an attempt to set a world record, some industry insiders said it would slow the seemingly endless rush to push skiing’s limits. Not so.

There are still people, of course, getting big air, and there’s still a market for it, primarily in the ski-porn films that are more popular than ever with platforms like Netflix and YouTube. The video cameras were there when Candide Thovex made the first successful flight over Chad’s Gap in Cottonwood Canyon, Utah, in 1999, throwing in a mute grab, and when he came back the next year and did it with a D-Spin. Yes, the same Chad’s Gap where Tanner Hall, after sessioning it well all day in 2005, came up short trying a switch cork 900 and broke both ankles. On video. He returned for redemption in 2017.

The cameras were running in 2006 when Jamie Pierre stuck a 255-foot cliff drop in the Grand Targhee backcountry of the Tetons. He literally stuck it, going in almost headfirst like a dart and having to be dug out. He’d worked his way up since 2003 from 165 feet to 255 during a series of big leaps in Utah, Switzerland and Oregon.

“I just really wanted to hold the record, even if only for a day,” he said afterward. With a young family, he noted he could now happily “retire” to slightly less hazardous skiing. Sadly, he died at 38 in 2009 in an avalanche in the Alta backcountry.

The heart-stopping heights of serious cliff hucks had progressed to the point in the 1990s where no one was even trying to ski away from them. They would simply plant their landings in deep snow, using the tails of their skis when possible to absorb some impact, and just hope to survive. That was Fred Syversen’s plan in 2008 when he made a filmed practice run, during a movie shoot, to a cliff in Norway chosen to break Pierre’s 255-foot record. But he turned too early in his fast-moving descent, and realized it too late.

“Braking or trying to stop was no longer an option, it simply went too fast,” he posted on social media. “So that left one choice: go for it and do it right!” He turned slightly to avoid rocks to his left, got out over snow and tilted so he didn’t land on his ABS pack that could have damaged his spine. He cratered like an unexploded howitzer shell. His only slight injury came when someone hit him with a shovel digging him out—351-feet later.

There’s also nine seconds of wobbly bystander footage (pure gelande still doesn’t get much love) of Rolf Wilson setting the alpine-jumping world record of 374 feet at Howelson Hill in Steamboat in 2011. You probably didn’t see it even if you lived in Steamboat. “It’s such an odd sport,” allows Wilson, who’s from Missoula, Montana. “One of the sports that doesn’t get a lot of recognition, because the guys that do it really just wanna jump, and see how far they go, and have fun. And we’re a bunch of hooligans to be honest with you.”

Jesper Tjader’s giant transfer in 2014, and David Wise’s 2016 blast, rocked the park and pipe world. And since then Big Air has seemed poised for the next big step. As some alpine jumping records near their survivable outer limits, no one has been lining up to try to beat Syversen’s 351 (12 years ago) or Wilson’s 374 (nine years ago). So what’s on the horizon?

More X Games-style productions; more ski movies; more genius films like Candide Thovex’s with amazing stunts that aren’t always potentially lethal; wing-suited jumpers regularly landing on slopes from big drops without ever popping chutes; and someone letting the true gelande crowd build the jump they yearn for with a lightning fast in-run, adjustable kicker, and endless run out.

Meanwhile, if you want to go really long the best bet is still Nordic ski flying on the 120-meter hills, where the current world record by Stefan Kraft of Austria at 831 feet is just shy of three football fields, no tricks involved.

Jay Cowan has written about skiing for five decades and received Colorado Ski Country USA’s Lowell Thomas Award for print journalism, multiple magazine feature writing awards from NASJA, and has been included in The Best American Travel Writing of the Year. His books include Hunter S. Thompson and his latest, Scandal Aspen.

Table of Contents

2020 Corporate Sponsors

World Championship

($3,000 and up)

Gorsuch

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Polartec

Sport Obermeyer LTD

Warren and Laurie Miller

World Cup ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

BEWI Productions

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Country Ski & Sport

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Descente North America

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association (NSAA)

Outdoor Retailer

POWDR Adventure Lifestyle Corp.

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Snowsports Merchadising Corporation

Sports Specialists Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply, Inc.

Gold ($700)

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

Silver ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Clic Goggles

Dalbello Sports

Dill McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

NILS, Inc.

Portland Woolen Mills

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snow Time, Inc.

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge & Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Vuarnet

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

For information, contact: Peter Kirkpatrick | 541.944.3095 | peterk10950@gmail.com

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!