By Seth Masia

We’ve all heard that ski resorts will operate this coming winter under social-distancing rules. That means limited cafeteria space, restrooms, chairlift seating, lift-line queues and equipment-rental facilities. Some of these limitations will be addressed by box lunches, new tented outdoor seating and Portapotties, and by online advanced reservation requirements. Many skiers won’t want to fly off on destination holidays, so some major resorts may see a drop in ticket sales.

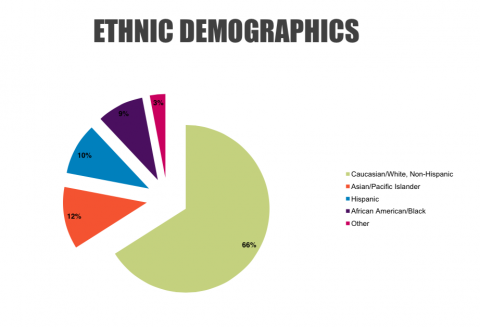

Meanwhile, in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests, companies say they plan to do more to address diversity issues. CEO Rob Katz of Vail Resorts sent out a letter to employees pointing out the obvious: the skier population is still very largely white, and so is his workforce. Katz has actually been out front on diversity issues, particularly with unprecedented female leadership and training at his company, but also with various programs (and personal donations) to get minority youth on the slopes. It hasn’t moved the needle much, he admits, and he terms this a “person failing.”

It’s hard to recruit new customers of any ethnicity at a time when businesses must ration access—and with the state of the economy. But staffing should be another issue. NSAA president Kelly Pawlak reports that half of resorts are understaffed, by an average of 44 positions. If visas for foreign workers remain unavailable and if international travel remains restricted, resorts won’t be able to staff up with young Latin Americans on temporary work permits. Resorts instead will need to find new seasonal staff, for jobs from mountain operations to cafeteria workers, perhaps in nearby cities—and local recruiting needs to begin now. Some of the new employees will be people of color. Close-in resorts may bus in workers. Destination resorts will have to ramp up availability of employee housing. If hundreds of nearby hotel rooms and condos are empty, as was the case at destination resorts during the Great Recession, that may not be a challenge.

One of the barriers to minority entry into the sport is that newcomers often don’t feel welcome when they don’t see other people like themselves in town. So more Black and brown faces in customer-facing staff positions would help to recruit new populations to the sport, once marketing outreach becomes practical again. Best of all: Some of the new employees will catch the mountain bug, stick around, and advance up the ranks.

Henri Rivers, president of the National Brotherhood of Skiers (NBS), has been talking to resort managers in Colorado, Utah and elsewhere. He points out that diversity needs to happen at all levels. Recruiting people of color for profit-center and senior management jobs isn’t hard. “But you can’t recruit the traditional way,” he said. “Outsource recruiting or look for other resources. Partner with the Black MBA Association or NBS, or with a Black lawyers’ association. Start by hiring four managers. They’ll be successful. There’s no shortage of highly qualified people eager to move out of the city into the mountains, for a better lifestyle.”

Skiing’s history is on the side of diversity. Going back to the early 20th century, once Norwegian immigrant ski clubs got over their resistance to the admission of English-speaking members—and notwithstanding the 119-year-history of anti-Semitism at Lake Placid and other Adirondack communities—the sport has generally accepted new arrivals. European refugees populated resorts beginning with the rise of Nazism, staffing ski schools and launching businesses. Postwar skiing in North America had strong roots in the fight against racist Axis governments.

Officialdom has had more trouble with new forms of snow-sport than with ethnicity. FIS took at least a decade to come to terms with alpine skiing, then with freestyle. More recently, in the 1980s and ‘90s, the sport’s leaders, and many skiers, fumbled badly with the integration of a new kind of customer—snowboarders. This relatively diverse group would eventually become saviors, pumping new life into a stagnant sport, then helping birth the freeskiing movement, which has been welcomed to resorts with untold resources dedicated to terrain parks. Back in February, a few months before George Floyd’s murder, the outdoor and ski industry suppliers banded together on a DEI pledge (diversity, equity and inclusivity). Pre-BLM, there had also been an upsurge in advocacy groups for diversity, ranging from industry- (Outdoor Afro) to consumer-based (Share Winter).

While the general skier population has remained largely of European ethnicity, ski areas have long drawn local ethnic groups as employees and customers, with several marketing efforts launched in the 1990s. Native American and Latinx skiers are unremarkable at resorts in New Mexico and Arizona, Asian skiers common at West Coast resorts. Black skiers remain under-represented despite the success of the NBS. This needs to change. The combination of the pandemic business disruption and the Black Lives Matter movement is an opportunity to accelerate that change.

Pie chart at top of page comes from 2013 SIA particpant study.