SKIING HISTORY

Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Seth Masia

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canad), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

A Brief History of Skiing Indoors

When there isn’t enough snow outside, skiers have headed inside for nearly a century.

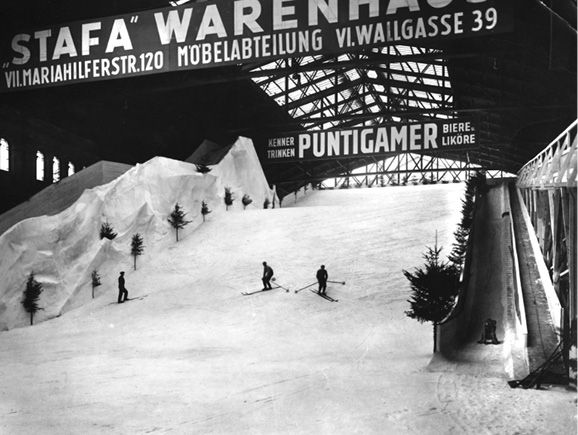

With trainloads of a mixture of sawdust, soda crystals and mica used to mimic snow, the first indoor ski center in Europe opened in 1927 in Berlin and helped launch the early era of indoor skiing (photo top of page).

first indoor black diamond run, a quad

lift, toboggan runs, and penguins.

Photo: Ski Dubai

Though Ski Dubai is frequently considered the cradle of indoor skiing, by the time of its opening in 2005 the concept was some eight decades old. Legions of people were already skiing indoors in dozens of countries—in some cases on bigger slopes already open in Europe and Japan. These facilities just hadn’t captured the public imagination quite as much as did the engineering miracles of indoor snow in the Dubai desert.

Fast forward to 2021, and we’ve recently passed the 150 mark for indoor-snow centers worldwide. True, there was a blip when the global economic crash of 2008 stopped some of the most ambitious projects of the time—including a 1.2 mile indoor slope proposed for the Middle East. But the past decade has seen more centers built than during the “boom” years of the 1990s. In fact, in the last few years centers have opened in Africa (Ski Egypt), South America (Snowland) and, finally, North America (Big Snow in New Jersey). Big Snow’s opening means that you can now ski indoors on a snowy surface every day of the year on every continent except Antarctica (where, let’s face it, you can ski outdoors every day of the year anyway).

For some that sounds like skiing nirvana: snowy slopes on tap whenever you need them, 365 days a year. For others, it’s a dystopian vision of the future of our sport: not skiing under blue bird skies surrounded by majestic peaks, but rather sliding down modest fall lines under a man-made dome. Or projected forward: Does the ultimate result of climate change and a warming world mean very little natural snowfall and therefore very few functional ski slopes?

It’s just a touch ironic that the massive refrigerators required to produce snow indoors and keep it cold use up a lot of energy, potentially contributing to climate change. But fortunately, that irony is not lost on the companies that build indoor centers. They incorporate energy efficiency to minimize running costs and in some cases cover their vast ski-center roofs with solar panels to generate the power needed to run the facilities. So is the future a utopian world of self-powered eternal indoor-snow centers? Perhaps worldwide statistics already reveal the future. In 2000, there were around 40 glacier ski areas in the European Alps where you could ski in summer and about 50 indoor snow centers. Two decades later, the count of glacier ski areas has dropped by more than half while the number of indoor-snow centers has tripled.

Europe 1920s

The idea of skiing indoors was first conceived in Europe in the mid-1920s. A Brit, Laurence Ayscough, patented something that kind of resembled snow—a mixture of sawdust, soda crystals and mica. This was then spread on top of straw on a sloping surface indoors.

Dagfinn Carlsen, closed in seven months.

The mixture’s first recorded use was within the Berlin Automobil Halle in Germany where a ski slope 720 feet long (220m) and 66 feet wide (20m) was opened in 1927. Trainloads of Ayscough’s snow mixture were required and government scientists had to approve its safety. The event was a success, and six months later a more permanent facility, the Schneepalast (Snow Palace), complete with an indoor ski jump, was unveiled at the disused Northwest Railway Station in Vienna, Austria.

Norwegian ski jumper Dagfinn Carlsen built the 41,000-square-foot facility, and there was plenty of publicity—though news reports focused on an assassination attempt on Vienna’s mayor after the event. Enthusiasm waned though, as people noted the chemical mixture wasn’t actually very slippery and quickly turned an unappealing yellow. The Snow Palace closed within seven months (see Skiing History, March-April 2019). However, a smaller facility, complete with a mini-ski jump, operated in Paris throughout the 1930s. Its snow had a different chemical mix to Ayscough’s concoction and was spread thinly on a coconut-matting covered slope.

US 1930s, Japan 1950s

The first known attempt to bring something like real snow indoors was not for a public ski facility but for a big show: The Great Indoor Winter Sports Carnival staged at New York’s Madison Square Garden in December 1936.

Garden boasted an 85-foot

ski jump, on crushed ice.

Complete with ski jumpers, dog sledders, ski stars from Europe and North America and even clowns on ice, the Carnival’s logistics were startling. An 85-foot high (26m) ski-jump tower had to be built by a team of 100 workers in a matter of days. Madison Square Garden’s thermostat was turned down to 26 degrees, then enough ice was pulverized to cover the 30,000-square-foot area with a snow-like surface. The show ran for four days and nights and attracted 80,000 spectators. Boston and London hosted their own Winter Carnivals in 1937 and 1938, with similar attendance success.

A related concept for indoor snow creation, but this time intended for more long-term use, appeared in Japan two decades later. Businessmen in the small city of Sayama, about an hour outside of Tokyo, hit on a way of extending the season. This time ice was trucked in from the mountains, again crushed to a “snow-like” material and spread on a 1,065-foot (320m) indoor slope. The Sayama indoor ski center opened in 1959 and is the oldest snow slope under a roof still operating. The snow surface is now made by snowmaking machines rather than hauled in by truck.

Australia, Europe and Japan, 1980s

The modern era of indoor skiing began in the mid-1980s when young Australian ski fanatic Alfio Bucceri created what he christened Permasnow.

In 1984, at the age of 28, Bucceri went skiing for the first time in Australia, was hooked and wanted to create the same experience in his home city, tropical Brisbane, 930 miles from the nearest snow. “I loved eating jelly as a child, and the Permasnow idea came from the thought of making small particles of jelly then freezing them. I studied ice rink technology and found that jelly crystals would freeze on frozen pipes at plus temperatures. Finally, I found the right safe chemical to use [a water-absorbent polymer] from an Australian manufacturer, engaged Queensland University to help and Permasnow was invented,” Bucceri recalls. “Funnily enough, the Japanese call it ‘Jelly Snow.’” Early trials were successful, but it was the Permasnow slope created for the Swiss Pavilion at the 1988 World Expo in Brisbane that attracted global publicity.

The first indoor-snow centers using Permasnow, at Mt. Thebarton in Adelaide and Casablanca in Belgium, opened that same year. Japanese rights were sold to the Matsushita Company, which created more than 20 centers in the 1990s under the Snova name, with some still operating today. Bucceri sold Permasnow in 1991 but remains in the all-weather snow business and developed a non-chemical, all-water snowmaking system that is used worldwide.

opened in 1993 but closed in 2002.

1990s, Real Indoor Snow

The success of the early indoor-snow centers led several pioneers to work on what, back then, was the holy grail of the concept: pure snow indoors, without chemical additives.

To create true snow indoors is much more difficult than outdoor snowmaking. Dealing with high humidity, constant refrigeration and maintaining the snow when hundreds of people are skiing the same patch over and over are just a few of the many challenges involved.

Several claim to have been the first to achieve it, one of them being Cor Mollin, a former alpine ski racer who started in the indoor skiing trade when he ran the Casablanca ski center in Belgium. He wanted to create Europe’s first indoor-snow slope and had made a four-day trip to the Brisbane World Expo to see Permasnow in action. He decided to license the product.

Back in Belgium, Casablanca was not a success. “The system didn’t work at all. As we had no refrigerated building, the jelly-snow wasn’t slippery and we almost went bankrupt,” Mollin recalls. “I then did research myself, and after a year of trial and error I built my first real snow machine. From that moment on we were successful in the snow business.” He went on to set up his own indoor snow slope, Snow Valley in Peer, Belgium, which remains in operation today and is one of the largest indoor ski halls in Europe.

The 1990s saw Japan and European nations dominate center construction, with ever-larger real-snow facilities in countries like Belgium, Germany, the Netherlands and the UK, all of which traditionally feed the destination ski resorts of the Alps.

Japan developed smaller Snova facilities, with the notable exception of the vast SSAWS (Spring Summer Autumn Winter Snow) indoor center near Tokyo, by far the largest yet seen, with a slope 1,640-feet long (500m) and 328-feet wide (100m). Unfortunately, it opened in 1993 as Japan’s bubble economy burst and it never turned a profit. It eventually closed in 2002, with the site later turned into Japan’s first Ikea store.

opens as China strives to put

300 million people on snow

before the 2022 Beijing Olympics.

Photo: Chengdu Sunac.

By 2000, around 50 centers had been built, and the next decade saw a similar number added. The longest slopes yet opened are in Amnéville, France and Bottrop, Germany. Both claim the world record at about 2,100 feet (640m) long.

China has been the dominant force in snow-dome construction over the past decade as the country builds towards the 2022 Beijing Winter Olympics and strives to meet President Xi Jinping’s publicized goal to persuade 300 million people to give snow sports a go.

However, most of the country’s 1.4 billion population don’t live in cold or mountainous areas, so indoor snow is the answer. More than 30 centers have been built, including several of the world’s largest slopes. Some even have indoor trail maps.

Should We Embrace Indoor Skiing?

Indoor snow centers are here to stay. When properly managed and located near a population hub, they’ve proved to be viable. Yet many skiers can’t imagine skiing on a short, moderate slope inside a

giant freezer.

Perhaps they’re missing the point. Indoor-snow centers don’t attempt to replace the mountain experience. Instead, their goal is to entice people around the world to conveniently try a sport they don’t know if they’ll like. No harm in that.

developers hope it will lead to more like

it. Photo: Big Snow

Big Snow. Big Money

New Jersey’s Big Snow epitomizes one key factor in almost all indoor-snow-center developments: They cost an awful lot to build, usually into the hundreds of millions of dollars. Far more centers have been conceived than ever opened. That said, of the 150+ that have now been built over the last 35 years, more than 100 are currently still operational. In that same time period, there have been few high-profile failures like Japan’s SSAWS center.

Big Snow is part of a huge mall complex in New Jersey created by the Mills Corporation, at the time an international leader in mall construction. Mills set to work on its multi-billion-dollar New Jersey project, then named Xanadu, at the turn of the century. Mills was also completing major malls on other continents at the time, including in Madrid, home to another Xanadu indoor-snow center which still operates today.

Big Snow was mostly completed around 2008, just before the global economic crash. Construction stopped, and it remained empty for 11 years before the complex finally began to open at the end of 2019.

Other developers hope that now that there finally is a facility in North America, many more will follow. The giant Triple Five Group that runs the mall where Big Snow is located has plans for a duplicate complex in Florida and the proposed green-energy powered Fairfax Peak in North Virginia.— PT

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

Sport Obermeyer

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

Warren and Laurie Miller

Yellowstone Club

GOLD ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sport

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboar Ski & Resort Corporation

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour