How a Seattle kid persevered and lived his dream.

Ed King is well known among Sun Valley locals as the only African-American ski instructor in the history of the resort. Considered by most ski historians as the birthplace and role model of American destination ski resorts, Sun Valley built its ski school around European-trained managers, who seemed to have been uninterested in the diversity of skiing talent on hand in its major market, Seattle.

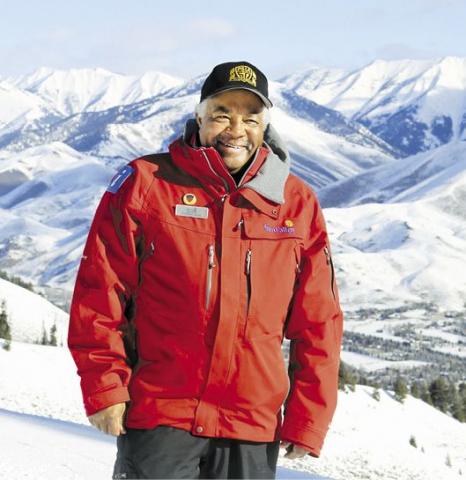

Photo above by David N. Seelig, courtesy Idaho Mountain Express

The few years King was a member of the Sun Valley Ski School are a small but significant part of his enormous contribution to American ski instruction and culture. The Seattle native began skiing in 1958 at age 11, after meeting Jim and Hans Anderson and their father, Hercules, in the YMCA swimming program. The Andersons, the best known among the few African-American skiing families in Washington at the time, invited King to Stevens Pass. “I took my first lesson and was hooked,” he recalls. “I told my Mom I was going to be a great skier. She replied, ‘We don’t have that kind of money.’ I replied that I will earn it, which I did.”

King was unintimidated by this Scandinavian sport. He came from a family of pioneers. His mother, Marjorie Pitter King, ran a successful accounting business and was the first African-American woman to hold state office in Washington. His aunt Maxine Hayes, after being denied entry to the nursing program at the University of Washington (UW), got her degree in New York; she then integrated the staff at Seattle’s Providence Hospital and became a professor of nursing at UW and Seattle Pacific University. His aunt Constance Thomas was the first African-American teacher in the Seattle Public Schools.

PTA Ski School, Seattle Ski Club

Seattle’s Parent Teacher Association (PTA) ran its own weekend ski program, and for several years King rode the PTA buses to Snoqualmie Pass. For three years he took lessons from the Japanese-American instructor Fred Hirai, and by the time King was in high school, he was a strong skier—strong enough that ski school director Hal Kihlman took the kid under his wing.

After attending ethnically diverse high schools (Garfield High in Seattle and Los Angeles High), King graduated in 1964 and headed to UW. Needing work to pay tuition, he taught swimming and diving for the Seattle Parks and Recreation Department and became a pool manager. In 1966, against some pushback from the resort owner, Kihlman hired him as a full-time ski instructor. A year later, King became the first Black member of the Seattle Ski Club. “I will never forget when Kihlman, Dan Coughlin and Keith Boender went to bat for me,” King says. “I remember them telling me it was quite a voting session!”

PSIA Certification and Sun Valley

King earned his full Professional Ski Instructors of America (PSIA) certification in 1968, and he may have been the first Black full cert. Kihlman contacted Sun Valley Ski School director Sigi Engl to recommend King as an instructor. Engl agreed to hire him. (Kihlman had neglected to mention King’s skin pigmentation.) Kihlman also introduced King to the late Gordy Butterfield, the rep for Head skis in Sun Valley. Butterfield, beloved in the ski industry and father of the accomplished ski photographer and historian David, invited King to live in his Sun Valley home while he tried out for the ski school.

King recalls the first ski school meeting he attended: “Gordy and I sat along the back wall. Sigi explained how we would be breaking into our clinic groups. It was the ’60s and I remember him saying in a certain room of the inn they would have the Head ski, which was the ‘Black Power’ ski, and in another room they had the [Kneissl] White Star, which was the ‘White Power’ ski. I turned to Gordy and asked, ‘What happened to the Hart Javelin?’ The Javelin was integrated: a white ski with a black stripe down the middle.”

King enjoyed a week of clinics with Don Reinhart, one of the founders of PSIA. He was then told to be available and meet every morning at the bus turn-around, where Engl made all of the teaching assignments. As King relates, “I showed up every day but was never asked to teach. It was difficult watching others with lesser or no experience being chosen. I kept a positive attitude, thanked Gordy for his hospitality and generosity, and returned to the Northwest. Two years later I returned to Sun Valley and again went through the process and again made myself available every day, but I was denied the opportunity to teach. This time it was quite painful, but I did not let it show. I knew I was a good instructor, but I was never given a chance.”

courtesy Idaho Mountain

Express

Ski School Founder, Director

Returning to UW, King majored in recreational planning and administration with a minor in art. During his final year, in 1972, he was offered a job at Evergreen State College, in Olympia, Washington, as associate director for leisure education programs. He took the job and graduated from Evergreen, where he worked and played handball with the legendary climber/philosopher/teacher Willy Unsoeld. He also developed programs and workshops in the arts for local communities.

King launched a PSIA-accredited ski school for Evergreen, supporting some students with financial aid through the Federal Work-Study Program. The school leased equipment at special rates from local ski shops, and Crystal’s Col. Ed Link came through with discount lift tickets. Wini Jones at Roffe helped with ski school uniforms and student skiwear. King invited the Grays Harbor YMCA to participate and began running buses from there and from Olympia and Tacoma to Crystal Mountain for lessons on Wednesdays and Sundays.

“Through this program we were able to provide an opportunity for students of African-American, Asian, Native American and Hispanic backgrounds the opportunity to experience skiing,” King says. “The ski program also offered an outdoor educational credit.”

Over the next 25 years, while running arts programs, King worked as an instructor, ski school supervisor, technical director and director. Meanwhile, he launched a successful photography business, built a pottery studio and helped to manage Seattle’s annual Bumbershoot Arts Festival. King was also hired by several corporations for special photography projects.

Sun Valley Redeemed

But he never lost his original dream of teaching skiing in Sun Valley. In 1995 he moved there with Eleanor, his wife since 1969, and let it be known that he wanted to teach skiing. In 1998, ski school director Hans Muehlegger and ex-director Rainer Kolb invited King to join the ski school. King said at the time, “It has been a very positive and enjoyable experience, and I thank Kolb and Muehlegger and all of the ski school for bringing me into the family. It is where I belong.” Muehlegger later hired another Black ski instructor, a British fellow who returned to Europe after one winter. King remains the sole African-American instructor to have worked at Sun Valley.

In 2005 the Kings left Ketchum for Spokane Valley, Washington. For a few years they returned to Sun Valley each winter, and King continued to teach with the Sun Valley Ski School. Then he joined the ski school at Silver Mountain in Kellogg, Idaho, as technical director—it was five hours closer than Sun Valley. But after more than 60 years of skiing, his knees needed some attention. He arranged knee replacement surgery, which was postponed by Covid. While waiting for new knees, King is busy running his photography business.

Of his skiing career, King says, “Sometimes dreams do come true. Many might take this for granted. I do not.” He adds, “If the entire world skied together, it would be a happier place. The happiest place on earth is the ski slope.”

Veteran racer, coach and author Dick Dorworth most recently reviewed Skiing Sun Valley in the July-August 2021 issue of Skiing History.