By Seth Masia

There's a thin line between avid reader and dedicated bibliophile.

The oldest known informed account of skiing for European readers was written by Olof Månsson, a Catholic prelate exiled in Rome after King Gustav Vasa established the Lutheran Church of Sweden in 1536. Under his Latinized name, Olaus Magnus, Månsson wrote an encyclopedic Description of the Northern Peoples, published in 1555 in Latin as Historia de Gentibus Septentrionalibus. It became a best seller and was soon republished in the Netherlands and translated into French, German, English and Italian. If you want a copy of the Latin first edition, prepare to pony up: Arader Galleries in New York prices its copy at $15,000, though Skiing History contributor Ingrid Wicken recently spotted a good one for sale in Oslo for $12,000. Or find a lightly used 1998 reproduction English translation, in three volumes, for around $120.

Woodcut above: The first reasonably accurate depiction of a Sami skier for European readers. Note the long gliding ski on the left foot and shorter, or pushing ski, on the right, with nutuka boots, a hunter’s crossbow and a single stick. From Schefferus’ Lapponia, 1673.

More than a century later, the law professor Johannes Schefferus (John Scheffer ) published Lapponia (1673), translated into English the following year as The History of Lapland. Scheffer, who also founded the science of archaeology in Sweden, corrected and expanded the description of Sami skiing, providing an accurate illustration thanks to the fact that he actually owned a pair of skis. You might pay $2,300 for a first edition of the English version, but you can read it, for free, at Project Gutenberg (gutenberg.org).

book inspired thousands to take

up skiing.

This is useful information for a skier who happens to love books. You know who you are. ISHA founder Mason Beekley assembled a library of about 2,100 volumes. Wicken has accumulated more than 5,000 titles. ISHA board member Einar Sunde guesses he owns about 3,000. ISHA’s research library totals around 1,900 bound books and manuscripts, plus lots of loose magazines, compiled from the collections of previous Skiing History editors. Henry Yaple’s ski bibliography of publications in English from 1890 to 2002 lists more than 7,000 items, including films and videos. Skiing Literature: A Chronological Catalogue, compiled by Gary Schwartz and Allen Adler from the catalogs of a dozen major collections, lists more than 2,500 first-edition titles (plus about 360 periodicals) published between 552 CE and 1994 in 11 languages.

Many book collections begin casually and accrete almost randomly. Some grow out of an academic or sports-writing career. Collectors sometimes lean toward specific genres, and the most sought-after volumes are often those that launched the category. Informally, we tend to classify ski books this way:

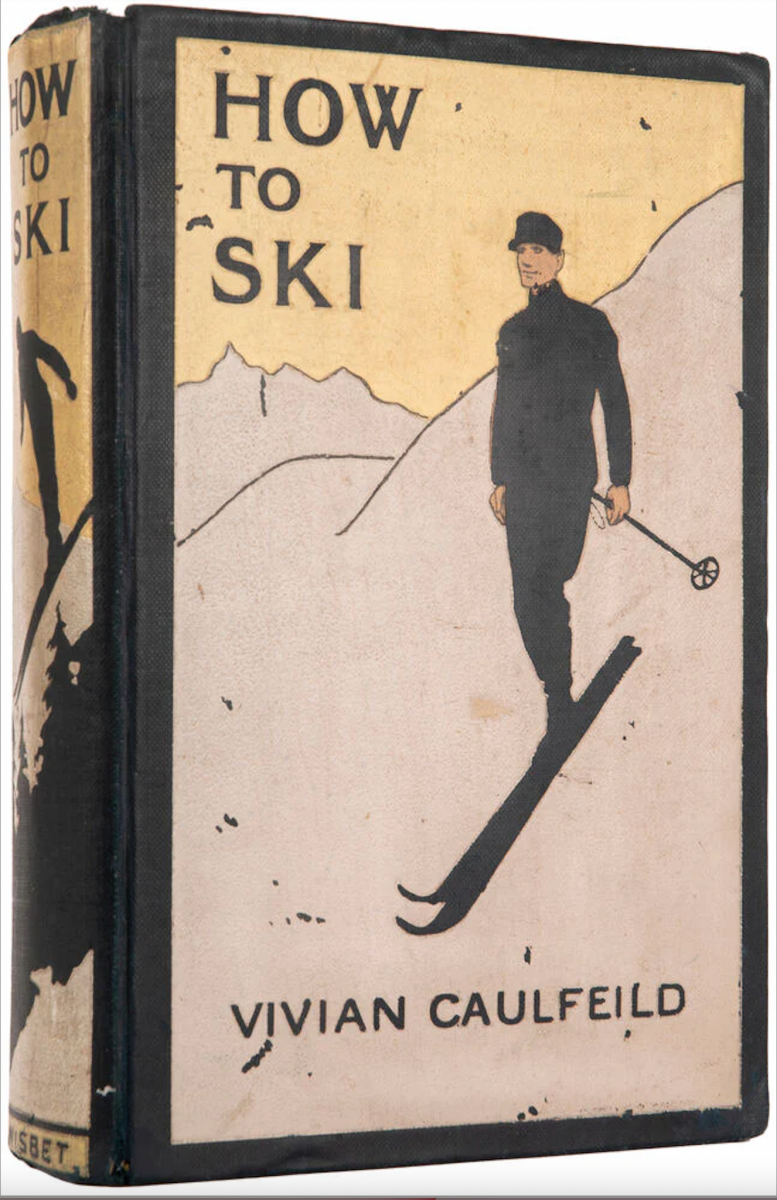

Instruction. We trace the history of ski technique by studying the how-to manuals. Important works include Oscar Wergeland’s Skiløber-Exercitie efter Nutidens Stridsmaade and Skytterlag og Skoler Tilegnet (1863); Mathias Zdarsky’s Lilienfelder Skilauf-Technik (1896); Georg Bilgeri’s Der Alpine Skilauf (1911); Vivian Caulfeild’s How to Ski and How Not To (1914); Das Wunder des Schneeschuhs, by Hannes Schneider and Arnold Fanck (1924); Ski Français, by Emile Allais with Paul Gignoux and Georges Blanchon (1937); Savoir Skier, by Georges Joubert and Jean Vuarnet (1963); and How the Racers Ski, by Warren Witherell (1972).

Caulfeild's influential manual

was How to Ski and How Not To.

History. Skiers have always been interested in the history of the sport. The first skiers were a complete mystery because they were pre-literate, so early histories tended toward speculation (see the influential and misleading history section in Fridtjof Nansen’s 1890 book, for instance). Among the first books in English containing a comprehensive review of the subject are Ski Running, by E.C. Richardson, Crichton Somerville and W.R. Rickmers (1904—also see Richardson’s The Ski-Runner of 1909), and A History of Ski-ing, by Arnold Lunn (1927). Authoritative modern overviews in English are The Story of Modern Skiing, by John Fry (2006), The Culture and Sport of Skiing, by E. John B. Allen (2007) and Two Planks and a Passion, by Roland Huntford (2008). The best summary of skiing’s archaeology is Les Peuples du Ski, by Maurice Woehrlé (2020; in French).

Subcategories include accounts of ski troops in World War II (including stirring, privately printed memoirs); local and regional histories; histories of jumping and ski racing; and institutional histories (college ski teams, ski clubs, associations and so on).

Coffee-table books. These large-format, expensively printed volumes feature photos of a resort or region. The text often comprises a local history—some are more authoritative than others—and a few are of quasi-academic quality. Many such books are commissioned to celebrate an anniversary of a resort. Where that’s the case, the history content can be hagiographic.

Biography. Every great ski racer eventually has a biography written about him or her, or pens an autobiography (often ghost written). Pick your own favorite athletes—hunting down their books is pretty easy.

Schneider and Arnold Fanck (1924) is a

seminal instructional manual from Alpine's

free-heel era.

Expeditions. Before there were satellite phones and video uploads, arctic explorers and ski mountaineers told their stories in print. The first and most influential of these was Fridtjof Nansen, whose På Ski Over Grønland (1890) kicked off a frenzy of interest around the world. The English translation, The First Crossing of Greenland, is a rollicking adventure and a detailed depiction of what skiing was like in the late 19th century.

Literature. Skiers tend to be well educated, and many write very well. Moreover, many well-known novelists have recounted (or fictionalized) experiences on skis. Look for ski literature by Arthur Conan Doyle, Arnold Lunn, Ernest Hemingway, Irwin Shaw, John Updike, Leon Uris and Oakley Hall, among others. Find excerpts in two great anthologies, The Ski Book (Morten Lund, Bob Gillen and Michael Bartlett, 1982) and To Heaven’s Heights (Ingrid Christophersen, 2021). But it’s more fun to find the original volumes.

Periodicals and serials. Because they contain articles written about specific events by eyewitnesses and participants, old magazines and newspapers are primary sources for historical researchers. Of special value in our work at Skiing History are the ski year books, published beginning after World War I by national ski associations. There’s the British Ski Year Book, the American Ski Annual, the Canadian and Australian Ski Year Books, and Der Schneehase (published in German, French and English by the Swiss Academic Ski Club). Also important is the British Public Schools Alpine Sports Club Year Book, which commenced publication in 1910. And in the post–World War II era, of course, there have been regional newsletters and national ski magazines.

Reproduction Editions A number of significant early book titles are available as inexpensive reprints, a boon to readers who don’t want to front upwards of $300 for a rare antique with a fragile leather binding. And if your interest is research, nothing beats the text-searchable digitized versions archived at gutenberg.org, runeberg.org and various university libraries, often for free.

Where to Find Books

Until the advent of search engines and online retailing, book collecting was a matter of poking through the dusty shelves and bins in a million bookstores dealing in used and antiquarian books. You found them in big cities and university towns; every shop had a cat dozing in the front window whose job was to minimize rodent damage to the inventory. Serious book collectors did business by mail, often employing agents who were intimate with the collections and bookstores in a region—Oxford, say, or Cambridge or San Francisco/Berkeley.

Today you can sit at a computer and find wonderful stuff without inhaling the detritus of a century. You can search for authors and titles in the books section of Amazon, but more serious collectors use ABEbooks.com, addall.com, alibris.com, biblio.com, bookfinder.com, thriftbooks.com and vialibri.net, which gather inventory lists from antiquarian booksellers around the world. It also pays to reach out to other book collectors: When a collector has a duplicate, there’s the possibility of negotiating a purchase or trade. Libraries and even ski museums occasionally sell duplicates, so it’s worth it to join their mailing lists.

Cataloging

Once your bookshelves start to fill, remembering where you stashed a specific title can be a challenge. Arranging everything alphabetically by author has its limitations. It doesn’t solve the problem of finding three or four books on a specific subject (World Cup racing, for instance); you really need a searchable catalog.

Cataloging is a painstaking process, and I’m only a third of the way through logging the recently arrived ISHA archive. My personal system is to label each book with a Yaple number (from Henry Yaple’s bibliography) or for books not listed by Yaple, my own acquisition number. I then record each number in a computer spreadsheet, with title, author(s), publisher and date, subject, acquisition source and date, special notes (e.g., a first edition) and shelf number. I can sort and search the spreadsheet for any of those items, then go straight to the physical location. Other collectors have their own systems.

Thanks E. John B. Allen, Kirby Gilbert, Ingrid Wicken, Einar Sunde and Bob Soden for valuable contributions to this article.