The 1940s: Americans Make Many Tracks…and Much war

The 1940s: Americans Make Many Tracks…and Much war

Authored by Morten Lund

World War II was three months old on New Years Day 1940, a time when most Americans simply did not want the United States getting involved in the European war. Minot Dole, who had organized the National Ski Patrol System in 1938, thought the U.S. was likely to get involved. At minimum, he thought, there ought to be a national mountain search and rescue outfit, preferably military, with the capability for winter rescue of the sort pioneered by the National Patrol. He proposed the NSPS take the responsibility.

The NSPS had already won its spurs. During the 1940-41 winter, its second season, the outfit had brought more than a thousand injured skiers to safety. It was obviously the largest nationwide experienced corps of rescue-savvy outdoorsmen. As a result, Dole was recognized as a leading expert in organizing field rescue teams in rugged terrain. Dole believed strongly that the Army should train not only search and rescue teams but have winter warfare capability. In 1940, it completely lacked both.

But America was officially at peace, beginning to come out of the Great Depression, and wanted no outside disturbances to interfere with the recovery. Life was beginning to be enjoyable. Everyone could afford a radio and radio shows were entertaining—Amos and Andy, Edgar Bergen and Charlie McCarthy, Fred Allen, George Burns and Gracie, all great entertainment. Everyone could afford the country’s weekly magazines so Life, Time, Collier’s, The Saturday Evening Post, The New Yorker were all immensely popular.

In the 1940s, the macho thermometer was registering a historic high-point. In skiing, the idea was that women were to ski but needed male support after they made their silly mistakes, as the December 21, 1940 cartoon cover of Collier’s made clear.

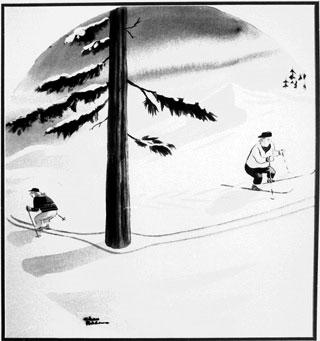

The urbane readership of The New Yorker wanted their ski humor more sophisticated. Nothing, in their view, could beat Charles Addams’ ski cartoon in a 1941 issue of the magazine showing single ski tracks going around both sides of a tree, very likely the most famous ski cartoon of all time.

The national trend to out-of-doors activity continued to grow healthily, and skiing along with it. In Quebec’s Laurentians, Mont Tremblant’s chairlift opened in February 1939, inaugurating the biggest and most sophisticated resort in the American Northeast. It was the sixth chair built in North America. Among the local innkeepers at Mont Tremblant were Frankie and Johnny O’Rear, who ran the resort’s Chateau Beauvallon, which Frankie immortalized as Chateau Bon Vivant, with cartoons by Lou Meyers showing what trouble lodge guests (often injured, wearing a cast) can be.

The same month that Mont Tremblant opened, February 1939, Hannes Schneider took over the ski school at Harvey Dow Gibson’s Mt. Cranmore, asking immediately for a second-stage Skimobile funicular to the top of Gibson’s Mt. Cranmore. Schneider got his wish, giving the state its third major lift (along with the Cannon aerial tram and the Belknap chairlift). In 1940-41, the first U.S. T-bar operated at Pico Peak, Vermont. The same winter, a chairlift was installed at Stowe, Vermont. By this time, Stowe’s was the 13th chairlift in North America.

In the West, Utah’s first ski lodge—the Alta Lodge in Little Cottonwood Canyon—a half hour from Salt Lake City, financed by the Denver and Rio Grande. Also in operation in 1939-40 near the lodge was a chairlift financed by Salt Lake City businessmen, cobbled together from long-unused mine hoists and other scavenged mining equipment, but it ran only fitfully until the 1940s.

The next winter, that of 1941, brought the first intimations of the American technology boon to come. Hjalmar Hvam, a Portland racer, marketed the first popular release binding, Saf-Ski, selling it under the alliterative slogan, “Hvoom with Hvam!”

In the fall of 1941, the U.S. Army made the decision to create an infantry regiment trained in winter and mountain warfare and authorized Dole’s National Ski Patrol to be the main recruiting outfit. The First Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry was activated, at Fort Lewis, Washington, on November 15, 1941, and soon began to fill with men recruited mainly through the NSPS.

Three weeks after the activation of the 87th, came the action that pushed America into World War II: planes from Japanese carriers attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Unfortunately, every officer in the 87th at Fort Lewis—including the commander—was new to winter and mountain warfare except German-speaking recruits. The considerable contingent of Germans, Austrians and Swiss enlisted in the 87th had all trained in mountain warfare since the age of 18 in their nation’s mountain troops. But the U.S. Army was not about to accept immigrants as officers, no matter how experienced in mountain warfare.

The 10th Mountain Division was activated in 1943, based at the training camp constructed at Pando, Colorado. The move to Pando was messy, the training sometimes confusing. The cartoons of Corporal L. Christian and Sergeant Dick Ericson in the February 1944 Ski Illustrated were on the mark in reflecting the average 10th Mountain recruit’s apprehensions and misapprehensions.

After the war in Europe was over, three 10th Mountain men—Friedl Pfeifer, Johnny Litchfield and Percy Rideout—joined forces in Aspen, Colorado. In 1945, they surveyed the mountain, cut trails and staffed the three-man ski school. In the spring of 1946, Pfeifer landed the backing needed to install two chairlifts he had ordered for the 1946-47 winter. From there on, Aspen succeeded against all odds in becoming the leading American high-mountain resort with the help of several squadrons of loyal 10th men holding down various posts within the resort. Without the 10th Mountain, Aspen would not have happened.

Although American resorts began to expand again in the aftermath of World War II, a good part of their potential clientele skied in Europe instead. European resorts had been winter spas for thirty years and actively sought the American clientele, the only one outside of the Swiss left with money after the thorough destruction of European industry in the war.

Swiss ski resorts, untouched by war, used their matchless sophistication and wealth of services to attract thousands of American soldiers and civilians who stayed on—and thousands more arriving—in Europe during the postwar era. Americans were appreciative that a stay at a classy Swiss resort was very very reasonable in then-strong U.S. dollars.

This sort of ski resort glamor, not to mention a certain touch of decadence, is implied in the cartoons of The Winter Book of Switzerland, published in 1949 by McGraw-Hill in London, New York and Toronto, obviously aimed at an English-speaking clientele with sophistication enough to gravitate to the comforts of European hostelry. Even those living in America with time and means to book an ocean liner could partake. In the 1950s, the newly-scheduled transatlantic Swissair flights turned a pleasing trickle into a fine flood.

It took the American resorts nearly two generations to match Swiss resorts in hotel comfort, dining, service and spa facilities. But in the meantime, they did begin to surpass the Europeans in grooming, snowmaking and chairlifts, goaded as they were by their native cartoonists who had been making no secret of the shortcomings to be found in American skiing: rocks, ice and the rope tow. -- Morten Lund