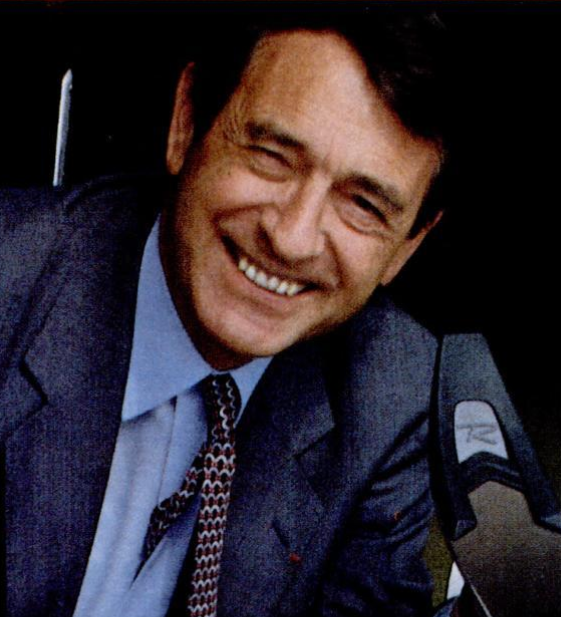

Laurent Boix-Vives, who drove the growth of Rossignol for half a century beginning in 1955, died June 18 at age 93.

Boix-Vives, son of a local grocer in Brides-les-Bains, was born in 1926, and at age 10 had watched Emile Allais win local races. At 18, near the end of the war, his father took him out of school to work in the grocery business, setting up new shops in the tiny mountain towns. Knowing the mountains well, Boix-Vives explored sites suitable for ski trails, focusing on the village of Moriond, which soon became Courchevel 1650. In 1953, the state government began offering contracts to develop lifts there; Boix-Vives jumped on the opportunity and got permission to build six lifts at Bozel, serving about 2,000 vertical feet of terrain, most of it tree skiing down to the valley towns below Courchevel. Eventually he built 21 lifts between Courchevel and La Plagne, and two at la Tania. He told his father the lifts would mean more grocery business. And he was right.

When Allais put him together with Rossignol, then near bankruptcy, Boix-Vives was enthusiastic. At the close of 1955, at age 29, Boix-Vives put up $50,000 and, with an additional investment from Philippe Cognacq and Courmouls Houles, two of his ski-lift partners, assumed control of Rossignol. “We also promised to pay off the factory’s debts within three years,” said Boix-Vives. “It amounted to another $100,000.”

His first move was to focus all activities on skiing. He dropped Rossignol’s money-losing weaving-machinery business, and reorganized product development under the technical supervision of Emile Allais and Abel Rossignol Jr.

With Boix-Vives’ funding, Allais and Abel, Jr. jumped straight into development of laminated aluminum skis, then, in 1960 commenced research into fiberglass skis. These were growth years in skiing, but making skis was a highly competitive, capital-intensive business, and not every factory prospered. While the French ski team forged ahead, on French skis, to become the dominant power in racing, the new Dynastar factory in Sallanches, near Chamonix, was barely paying its bills. In 1967 the plant grossed 16 million francs—about $3.2 million at then-current rates—and lost 16 million francs. Boix-Vives bought the company for a single franc, thus acquiring a second production facility.

In some ways, the era from 1968 to 1972 was the top of the arc. Canada’s Nancy Greene established a solid Rossignol brand franchise by winning everything in sight on Stratos, and America’s Barbara Ann Cochran won her gold medal on Rossignols at Sapporo. Meanwhile, most of the top French and American men diluted their brand value by bouncing around among Rossignol, Dynamic, and Head. Jean-Claude Killy, for instance, usually skied GS on Rossignol Stratos, slalom on Dynamic VR17s, and downhill on whatever was fastest. The exceptions were the Grenoble Olympics, when he skied all three events on Dynamic skis. Then, to even things up with his friends at Rossignol, he skied Rossignol for the rest of the World Cup season. From 1968 onward, Rossignol athletes never failed to win at least seven medals in any Olympiad.

In 1970, Rossignol built a new, fully modern plant near Barcelona. In these pre-European Union days, Spain was a cheap-labor country, and the new factory would become, over the next 30 years, Rossignol’s biggest, most efficient facility. Another acquisition that year was the Authier factory in Stans, Switzerland.

By 1972, Rossignol was the number one brand in the world. Boix-Vives was honored in 1976 by Prime Minister Raymond Barre with the title Manager of the Year. New factories went up in Vermont and Quebec, and Rossignol bought tennis racquet factories in Maine and Massachusetts. The tennis venture proved disastrously mistimed, as Rossignol ran straight into Howard Head’s new oversized Prince racquet.

Boix-Vives set up wholly owned distribution companies in North America for Rossignol and Dynastar, headquartered in Williston and Colchester, Vermont. Rossignol took over its own distribution in all major markets. North America soon provided 40 percent of Rossignol’s annual volume.

In 1973, the U.S. economy was hit with a double-whammy: National debt had soared to pay for the Vietnam war, which led to higher interest rates, and the first OPEC oil embargo sent gas prices zooming—and to weekend gas rationing, just when customers wanted to go skiing. Moreover, with the rise of freestyle and mogul skiing, racing was no longer perceived as the premium venue for marketing skis—and that hurt Rossignol in particular.

Ski sales flattened. Boix-Vives reacted by diversifying into new product lines: Rossignol launched a fabulously successful joint venture with Nordica to distribute the boots in North America, then introduced cross-country skis in 1976. Boix-Vives bought the Lange boot factory in 1978 as a personal investment, and Rossignol built a ski pole factory in 1980. Only 49 percent of Rossignol stock was publicly traded, so Boix-Vives was assured of control. For some years, Lange distributed its own brand of skis made in the Authier factory.

By 1984, Rossignol’s market capitalization had more than doubled to $52 million.

Boix-Vives resumed a program of sports acquisitions. He bought Jean-Claude Killy’s Veleda clothing factory in 1984, and Cleveland Golf in 1990. In 1994 Rossignol acquired the Look and Geze binding factory in Nevers, and the Caber ski boot factory in Montebelluna, rebranding these products with the Rossignol logo. Ownership of Lange was folded into the Caber operation, and the two factories shared their race boot technology. The empire sold off the Authier plant to a group of local Swiss investors and placed distribution of Lange boots and Look bindings with the Dynastar organizations worldwide.

The consolidation came just in time. In 1989 Rossignol acquired a powerful new competitor in the ski market—Salomon. Over the next five years Rossignol would scramble to match Salomon’s sleek and well-marketed cap ski technology, and then, after 1993, play catch-up to Elan, K2, and the Austrians in the new shaped-ski revolution.

During the 1990s, companies that moved more quickly into new ski technology gained market share, largely at the expense of Groupe Rossignol ski brands. Success in the boot and binding markets kept the company profitable. According to Hugh Harley, president of Rossignol’s U.S. operation at the time, the highly automated efficiency of the Spanish factory, which retooled quickly to build less-expensive shaped skis, enabled the ski division to squeak through and regain prominence in the low price points.

Boix-Vives wasn’t an equipment or machinery designer like his rivals Paul Michal, Alois Rohrmoser, or even a product fanatic like Josef Fischer or Georges Salomon. He was a bona fide ski racing nut, putting nearly 3.5 percent of gross sales straight into the powerful racing operation. But first and foremost, Boix-Vives was a financial wizard. “Time and again he was able to turn around companies in trouble,” said Lanvers. “Part of it is that he set up a clever organization to sell currency futures and make currency fluctuations work for him. But the most important thing is that he had the ability to divorce himself from the nuts and bolts, step back, and see the big picture.”

The 50-millionth Rossignol ski was built in 2004 During the new millennium, the dollar dropped to historic lows relative to the Euro—hitting EUR .76 in 2005. Rossignol’s profitability plummeted. Part of the problem was that Rossignol was still making skis and boots in Western Europe, while most of the competition— including the large Austrian companies—had reacted to the sinking dollar by moving much of their factory capacity to China, the Ukraine, Romania, Bulgaria and other cheap-labor nations. To keep prices competitive, Rossignol had to slash its wholesale margins. The 2003-2004 and 2004-2005 winters saw late snow in key markets, and sales stalled. Rossignol posted a solid loss.

In March 2005, at age 78, Boix-Vives faced retirement. He sold his controlling interest in Rossignol to the Australian/American sporting goods company Quiksilver, then run by his friend Bernard Mariette. SEC filings show that the terms of the sale valued Rossignol at approximately $312 million, with debt about $158 million and revenue of $630 million. The deal included a $55 million cash payout to Boix, but apparently treated his original partners, Philippe Cognacq and Courmouls Houles, as common stockholders.

Quiksilver consolidated all North American snowsports operations—Rossignol, Dynastar, Lange, Look, and their related snowboard divisions—in Park City, Utah, and sold the Voiron factory grounds to a real estate developer. Quiksilver then lost about $50 million in the wintersports divisions and in 2008, was acquired by the Australian bank Macquarie. In July 2013, Macquairie sold the Rossignol Group, along with its subsidiaries Lange and Dynastar, to a partnership controlled by Altor Equity Partners,a Swedish investment group..

In 2009, Laurent Boix-Vives and his wife opened a 5-star hotel in Courchevel, naming it Strato. --Seth Masia

Condensed from 100 Years of Rossignol Photo by Del Mulkey

Comments

A radically different view of business

I had the pleasure and honor of working for Laurent Boix-Vives while at Lange from 1982 through 1986.

Not only did this help me raise my young family, gave me some strong, practical experience in the boot business, facilitated my move to the Rocky Mountains when we set up a new R&D center in Salt Lake City, but it also helped me understand how to make a tricky seasonal ski business more financially viable.

He also cannot be dissociated from his very different, yet quite successful competitor, Georges Salomon, who left us a decade earlier. Salomon was obsessed with the product, its marketing and a quest for innovation, whereas Boix-Vives who supported ski racing wholeheartedly, was more of a public person who loved the financial side of business and enjoyed contacts with the who-is-who of captains of industry and politicians.

Add new comment