NASTAR’s mid-1970s national coordinator fondly remembers the low-tech camaraderie of the racing program’s early days.

By 1973, under the direction of former U.S. Ski Team coach and director Bob Beattie, NASTAR had expanded from the original eight to 80 ski areas, attracting recreational skiers to make 80,000 runs. With such rapid growth, Beattie—who was also running the World Pro Ski Tour—needed to expand his staff.

In the mid-winter of 1973, Bob Beattie decided to hire a public relations director for NASTAR, a job that had been held by Aspenite Greg Lewis. When Beattie tapped Lewis to announce his World Pro Ski Tour races, the NASTAR job opened, and I took it. By that spring, I’d been promoted to NASTAR national coordinator.

It was a swift change of gears for me, a totally new world of big money, credit cards, expense accounts, fancy restaurants and lodges. “Nothing like going to restaurants where no entrée is under $7!,” I remember thinking at the time. But it wasn’t hard to get used to.

Back then, NASTAR operated in a low-tech world. To process results, we used a futuristic computer something akin to “Hal” of the then-popular film 2001 Space Odyssey. Hal sat in a cool, dark facility in Boulder. At our headquarters near the Aspen airport, we sorted hand-written weekly race results that we then shipped via courier to Boulder for punch-card processing, ultimately determining national finalists and other awards. Our office ran on Selectric typewriters, land lines, snail mail and hand labor.

SETTING THE PACE

The NASTAR season got underway each year with the December pacesetting trials to determine the national zero handicapper against whom all NASTAR scores were compared.

We traveled the country to run these events. Some memorable moments: torrential rain and impenetrable fog at Crystal Mountain, Washington; Indianhead, Michigan, where the local drink was cheap brandy and soda; too much snow and broken timing equipment at Sugarbush, Vermont; perfect venues and perfect hosts at Waterville Valley (New Hampshire), Alpine Meadows (California) and Vail (Colorado); and the Eastern Slopes Inn at Mt. Cranmore, where the pacesetters flocked to the indoor gym and pool after midnight.

Austrian triple Olympic medalist Pepi Stiegler, director of skiing at Jackson Hole, was the perennial zero handicapper during my NASTAR stint, 1973 through 1977. He wasn’t unseated in my era. I recall watching Pepi slip effortlessly through the gates on Vail’s Golden Peak, with World Pro champion Spider Sabich waiting at the bottom, holding the lead. Pepi won again. “He doesn’t even look fast,” said Spider. “How the hell does he do it?”

Spider and other stars of the World Pro Ski Tour—Olympians Hank Kashiwa, Otto Tschudi and Moose Barrows among them—brought PR glitz and personality to NASTAR. Touring pacesetter Barrows stood inside the day lodge atop the Indianhead slopes one year, skis and goggles on, fully suited and booted up. It was 30 below zero. He ventured outside only long enough to make his runs. Another time, we arrived in the dark of night at the massive Telemark Lodge in Cable, Wisconsin, with Alpine Meadows pacesetter Jorge Dutschke in tow. When we headed outside the next morning, he said, “I can’t see the ski hill; the lodge is in the way.” Hill vertical: about 300 feet.

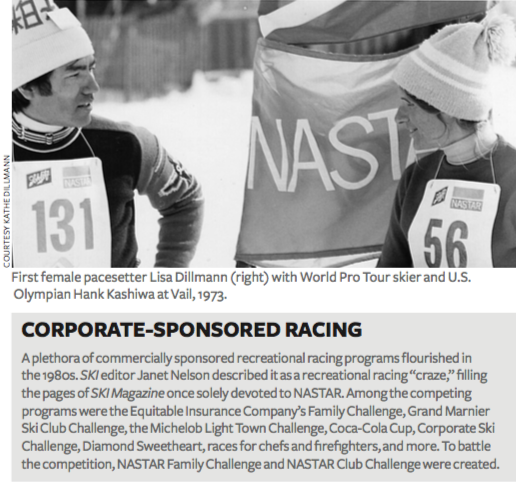

Early on my twin sister Lisa was the only female pacesetter running with the men pacesetters, at the Vail trials, before Bonne Bell initiated its women’s pacesetter program. Keystone founder Max Dercum was perennially our oldest pacesetter, in his 50s at the time. Max personified NASTAR’s raison d’etre: pacesetters and racers alike all earned their handicaps when scored against Pepi’s time, adjusted by age.

SPONSORS COME AND GO

My first big NASTAR road trip was to Vail in mid-season 1973 to jumpstart the new Johnnie Walker Red Cross-Country NASTAR, with its own pacesetting trials. With my NASTAR colleagues, we welcomed a stalwart group of cross-country pros, including the hard-charging Ned Gillette, out of the Trapp Family Lodge in Stowe, who would go on to become one of the most successful big-mountain climbers and skiers of his generation.

That sport was still in its infancy in the U.S. and this sponsorship was a mismatch lasting but one season. Granola-crunching Nordic skiers and ski bums were not scotch drinkers. As the corporate bigwigs feted us, we quietly poured their sponsored beverages into nearby potted plants.

That sport was still in its infancy in the U.S. and this sponsorship was a mismatch lasting but one season. Granola-crunching Nordic skiers and ski bums were not scotch drinkers. As the corporate bigwigs feted us, we quietly poured their sponsored beverages into nearby potted plants.

Doral cigarettes came on board the alpine NASTAR early on with a special windshirt prize. There was no such thing as an anti-smoking movement back then. Their execs in Winston-Salem had rarely seen snow and none of them skied. Small wonder they soon left NASTAR for bowling and stock car sponsorships.

Bonne Bell was the first successful promoter of colorless sunblock lotion. No more zinc-covered clown noses. Their all-female Ski Team supplied glamour along with cases of product.

Pepsi got what it wanted from its sponsorship of Junior NASTAR: NASTAR resorts had to agree to pour Pepsi, not the other big brand. With NASTAR’s growing popularity, it was a profitable deal for their regional distributors.

We enjoyed a great relationship with Schlitz beer. Their white-haired, mild-mannered PR pro Don Dooley was an avid skier and a real workhorse who helped us through many a mad scramble posting Finals press releases, working alongside us well past midnight every year. We snail-mailed at least one release per competitor, with photograph, to each finalist’s hometown newspaper—more than 100 pieces, all handled manually.

SNAFUS IN THE OFFICE

SNAFUS IN THE OFFICE

The shared headquarters of NASTAR and the World Wide Ski Corporation was always chaotic and never dull. The office was ably managed by the colorful Jenni Seidel, who kept things rolling through storm and calm. She was infamous for kicking the copier to “fix” it; when that failed, she dumped wine into the toner. It worked!

Imagine what it cost NASTAR for a marketing director’s blunder in ordering thousands of promotional posters he’d commissioned—a cartoon facsimile of Superman donning ski clothing in a phone booth—“From skier to racer in a single bound.” We were issued a cease-and-desist order by Marvel Comics and the whole truckload had to be dumped.

One season a large batch of enameled NASTAR medals incurred serious chipping. There were a lot of unhappy customers. We got the problem fixed in a hurry, sent nice letters out with new medals and put that issue behind us. But I’ll never forget the charming hand-written note from one seven-year-old Squaw Valley girl thanking us for sending her a new medal. “Your letter is funny. The metal [sic] is pretty,” scribbled little Edie Thys [Morgan]. I always like to think NASTAR was Edie’s jumping-off point to the U.S. Ski Team and the 1988 and ’92 Olympics and her subsequent career as a ski writer.

THE SCHLITZ NASTAR FINALS

The Schlitz NASTAR Finals were a big deal. How we managed it all without computers, email and fax machines is amazing to contemplate in today’s high-tech world.

Hal the computer spit out the results by mid-March, tapping the top regional recreational racers with the lowest handicaps, male and female, in adult age classes. The biggest miracle was how we got all of them to the same airport, at around the same time, from all points of the compass. We had to telephone each of 80 winners and arrange for their travel, coordinated by the doggedly efficient Aspen Travel agency.

The NASTAR Finals of that era were an expense-paid trip for the finalists—free air, lodging, and bus to the venue from the airport. Nothing was more gratifying than calling up a winner and announcing, “You’ve won a free trip to the NASTAR Finals.” The responses were hilarious, some thinking we were a crank call, others screaming to family members in the background, but all buckling down to help us get them to the big event. Their excitement was contagious, even though we were exhausted by then.

They came from all over the country, from all walks of life, of all ages, body shapes and sizes. There were no racing suits, no helmets, no special racing skis. It was competing for the pure fun of it. Out of hundreds of finalists in my NASTAR days, two come to mind who may jog the memories of Skiing History readers.

Goldie Slutzky, wife of Izzy, founder of Hunter Mountain with brother Orville, made the cut in 1974. The Finals were at Sun Valley, where four different weather patterns assaulted us—rain, hail, snow, fierce winds. There was no sun in Sun Valley. But our finalists were undaunted, least of all Goldie, whose bubbly personality buoyed all of us. When she completed her first run, she collapsed in a heap past the finish line. We rushed to her aid, only to hear her giggling. When we got her on her feet, she whispered, “I’ve split my stretch pants.” Quickly remedied with a draped wind jacket, Goldie carried on.

Then there was 10th Mountain Division veteran J. Arthur Doucette from the Mt. Washington Valley of New Hampshire. He qualified for the Snowmass finals in 1976, at age 68 the oldest competitor I remember. He was on his sixth pacemaker and, at altitude, required an occasional nip from an oxygen tank. After completing his race runs, Arthur donned his full 10th Mountain rucksack and white-camouflage uniform and skied the course again to wild cheers.

The NASTAR finalists loved to ski and loved NASTAR. Though they came to compete, winning was not foremost in most of their minds. It was the spirit of NASTAR that bonded us all. Such memories last a lifetime.