From the 1960s through the 1990s, a series of U.S. entrepreneurs—including Friedl Pfeifer, Bob Beattie and Ed Rogers—took turns trying to make pro ski racing a success.

Counting only prize money, this season’s highest-ranked alpine ski racer—Tina Maze of Slovenia, with 11 World Cup wins and 24 podium finishes—earned 701,797 Swiss francs, or about $726,000. That tops the prize earnings of friend and rival Lindsey Vonn of the United States, who pulled in about $220,000. The number-one male skier was Marcel Hirscher of Austria, who won $554,286. In the 2012–2013 season—the 21st winter since the Federation Internationale de Ski (FIS) first began to allow cash purses—more than $8 million in prize money was distributed on the World Cup alpine circuit. This doesn’t include dollars that athletes earn from other sources, like product endorsements: According to ESPN, Vonn’s total haul this year was $3 million.

Counting only prize money, this season’s highest-ranked alpine ski racer—Tina Maze of Slovenia, with 11 World Cup wins and 24 podium finishes—earned 701,797 Swiss francs, or about $726,000. That tops the prize earnings of friend and rival Lindsey Vonn of the United States, who pulled in about $220,000. The number-one male skier was Marcel Hirscher of Austria, who won $554,286. In the 2012–2013 season—the 21st winter since the Federation Internationale de Ski (FIS) first began to allow cash purses—more than $8 million in prize money was distributed on the World Cup alpine circuit. This doesn’t include dollars that athletes earn from other sources, like product endorsements: According to ESPN, Vonn’s total haul this year was $3 million.

(This article first ran in the May-June 2013 issue of Skiing History).

Professional ski racers lag behind the superstars of other sports when it comes to annual earnings—Vonn’s annual earnings are about a 20th of what boyfriend Tiger Woods pulls in on the golf course, for example. But their careers can still be relatively lucrative. This is thanks partly to the pro racing movement, which confronted the politics of amateurism in the 1960s and affected competitive racing for all time.

Clashing Over Shamateurism

As early as 1936, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the International Ski Federation (FIS) were clashing over the role of money in ski racing. That year, the IOC announced that ski instructors were to be considered “professionals” and were therefore ineligible to compete in the Winter Games at Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany. Austria and Switzerland withdrew their top alpine racers in protest. By 1952, when Chicago millionaire Avery Brundage took the helm of the IOC, the stage was set for a showdown. “Brundage was a man obsessed with the idea of pure amateurism,” writes John Fry in his book The Story of Modern Skiing. “He regarded alpine racers as a cancer within the Olympics because of the money paid to them by equipment companies to use their products.”

Meanwhile, alpine racers found an outspoken proponent in FIS president Marc Hodler, who argued they should be allowed to earn money to cover the high cost of training and racing, which far exceeded the expenses of, say, swimmers or track and field athletes. Sir Arnold Lunn concurred, saying that “fake amateurism” encouraged perjury as athletes swore they were amateurs in order to compete in the Olympics.

The long-running battle between Brundage and Hodler heated up when Brundage publicly demanded that racers from the 1968 Grenoble Olympics—including triple gold-medal winner Jean-Claude Killy—return their medals. He also demanded that a slew of racers be barred from the 1972 Games in Sapporo, Japan. In the end, the only racer to be banned was Austria’s great slalom skier, Karl Schranz, the three-time world champion and World Cup overall champ in 1969 and ’70. Schranz, who was considered a favorite in the ’72 Games, was excluded on grounds that his consultant status with equipment manufacturers, most notably Kneissl, had tainted his amateur status. His expulsion triggered outrage in Austria (where Brundage was burned in effigy) and around the world. As Fry writes, it was a watershed event in the history of the Games, and one that ultimately “turned out to be the funeral…of the amateur ideal in the Olympics.” Brundage stepped down later that year.

Friedl Pfeifer and Pro Racing in America

While the IOC and FIS were duking it out over the Winter Games, a professional raci

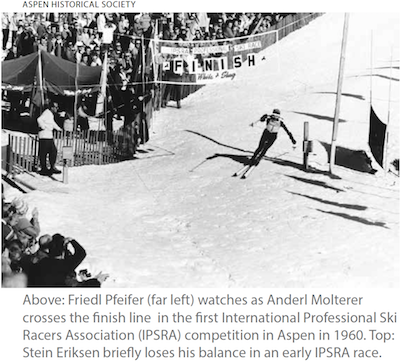

ng circuit was gaining traction in the United States. It was led by Friedl Pfeifer, one of the founders of the Aspen Skiing Company who helped to build the Colorado resort after World War II. As a ski instructor in his native Austria, Pfeifer had been barred from the 1936 Games for his “professional” status. So he had a certain passion in 1960 when he founded the International Professional Ski Racers Association (IPSRA), stamping it with a ringing rationale. “I want (ski racers) to have the opportunity to be compensated for what they have given to the sport,” he said. “With that in mind, I set out to start a professional racing organization.”

The ski world took notice as Pfeifer organized a cadre of the most famous names in skiing: Minnie Dole, Sigi Engl and Willy Schaeffler in administration; Howard Head as the initial sponsor; and racers such as Toni Spiess, Anderl Molterer, Stein Eriksen, Pepi Gramshammer and Othmar Schneider. The initial races were held at Buttermilk in 1960.

“The FIS heard about my project,” wrote Pfeifer in his biography, Nice Goin’ (ghost-written by Morten Lund), “and urged the U.S. Ski Association to notify resorts of the consequences of hosting an IPSRA race. The resorts were warned that if they supported or sponsored the professional ski races in any way they would be disqualified as a future host for an FIS championship event.”

Despite the warning, the fledging pro ski tour survived for six fairly vigorous seasons until Pfeifer turned the tour over to the racers themselves, who formed the Professional Ski Racers Association with Killington’s Karl Pfeiffer (no relation) heading the group. After the championship races in Japan the next season, Pfeiffer held a meeting to tell racers that he didn’t have the time to chase new sponsors. In 1969, wrote Friedl Pfeifer, “The torch was passed on once again, this time to Bob Beattie.”

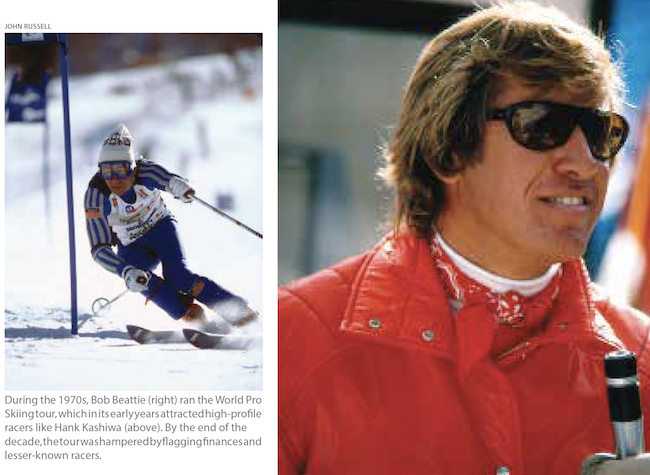

Bob Beattie Takes the Reins

The 1970s started well for Beattie’s tour, featuring high-profile U.S. racers like Billy Kidd, Tyler Palmer, Hank Kashiwa, Scott Pyles and a 25-year-old from Aspen with dazzling blond good looks, Vladimir “Spider” Sabich, who had scored 18 World Cup top-ten finishes. Sabich won the first two pro events he entered, taking home a modest $21,189 in prize money. But the charismatic racer, whom some suspect was the inspiration for Robert Redford’s character in the movie Downhill Racer, also had product endorsements that brought his earnings to $100,000. He soon earned the nickname “Mr. Pro.” When Killy joined him at the start of the ’73 tour, pro racing seemed to be the ascendant rocket of the sports world, with product endorsements coming on strong and TV dates filling the season calendar.

Instead, enthusiasm dampened that year when the tour took an unpredictable turn and two relative unknowns—Austrian racers Hugo Nindl and Harald “The Stork” Stuefer, a gangly athlete who stood six feet, five inches tall—won the opening events. In the end, Killy took the season title, mollifying sponsors and television executives. But the potential weakness of pro skiing was becoming clear: Without big names, the buzz soon quieted.

In 1974, Nindl won the title, and a record $93,230 that stood for many years. But again, when unknowns such as rookie Josef Odermatt displaced better-known skiers, Beattie knew he had

to come up with a plan. Meanwhile, the tour’s chief sponsor, the cigarette company Benson & Hedges, pulled out of ski racing. In 1975, the schedule forced a five-week break in mid-season, and the tour seemed to be faltering.

Aspen hosted a four-race Aspen Pro Spree event in 1976 at a time when hometown hero Sabich was struggling on the slopes. A French skier, Henri Duvillard, soared on the tour that year, winning three of the four Aspen races and adding 13 more wins to dominate the season and win him an honorary title, “The Frog Who Ate the World.”

The season seemed fairly successful until March, when Sabich was shot to death. His girlfriend, the actress Claudine Longet, was arrested for manslaughter and sentenced to a short term in prison.

By the end of the decade, the tour was still suffering from a familiar demon—unknown ski racers—and so Beattie devised a plan to alter the seeding system to guarantee that some top names would at least get through the qualifying rounds. The maneuver helped a bit; the season finished with two veterans, Hans “Hansi” Hinterseer and Lanny Vanatta, taking serious but unsuccessful runs at Austrian Andre Arnold.

The following season, with his finances flagging, Beattie’s tour unraveled. Arnold was still dominating early, and the season played out until April, when a handful of racers—including Hinterseer and Boston’s Richie Woodworth—boycotted a race, claiming that a snowstorm had made course conditions variable and unfair. With national TV ready to roll, the boycott was disastrous for Beattie, who disbanded World Pro Skiing a few weeks later.

The Era of Ed Rogers

With no major leagues left, regional minor-league tours partially filled the void, including a Coors-sponsored American Pro Ski Tour out of Colorado and a group of racers organized by Maine restaurateur Ed Rogers and partner Mike Collins, who signed a sponsorship deal with the French car company Peugeot. After a sensational Eastern meet at Mt. Snow in Vermont (Wayne Wright fought hard to beat Georg Ager for the title), the two regional tours were combined once again into a national tour. Rogers, who owned the famed Red Stallion Inn at the Sugarloaf ski resort in Maine, says, “We had the B tour, but when Beattie went out, a lot of his skiers came over to us.”

In the mid-1980s, the Viking assault was on, in the form of Norwegian brothers Jarle and Edvin Halsnes and their buddy Reidar Wahl, who won the tour in 1984. Jarle won the title in 1985 and Edvin beat him the next year. Jarle was back in 1987 before Sweden’s Joakim Wallner broke the brothers’ grip in 1988, the year that Jarle, suffering from a bad back, announced his retirement. In his 1987 win, Jarle pocketed $103,750, finally topping Nindl’s earnings mark that had stood since 1974.

In October 1988, Rogers announced that he had signed the country’s two most successful amateur racers, twin brothers Phil and Steve Mahre, who had won gold and silver medals respectively in the 1984 Wint

er Games in Sarajevo. Phil explained that they needed the cash to fund a race car, and yet bad-mouthed the pro tour as a group of “has-beens and never-weres, including myself.” Mahre’s opinion aside, the tour that year was stacked with stars, including two Austrian aces—Roland Pfeifer and Bernhard Knauss, who had lost his place on the Austrian national team because of illness.

In 1989, Phil Mahre placed second but still pocketed $82,000 for the season. Meanwhile Chrysler-Plymouth liked what they saw and came in as a major sponsor. Mahre, who bad-mouthed the tour as too easy, still worked hard to master the dual-elimination format, ending up 3rd in the 1990 standings. But Knauss was coming on strong.

At first, Knauss was unable to overtake Pfeifer who, in 1990, cashed in with record earnings after winning both the tour and the Plymouth Super-Series Championships for a record haul of $221,816. The following season, Knauss hit the jackpot for $356,256, and then sweetened it the following year b

y winning $364,038 and knocking off Andre Arnold’s old record with 46 career wins. The next season he passed the million-dollar mark in career earnings. He would go on to win 76 races by the end of the tour in the late 1990s, with career earnings of about $1.5 million.

Though there had not been an American winner on the tour since the Mahre years, in 1996 Erik Schlopy from Park City won Rookie of the Year honors with a 6th place finish, as Knauss finally relinquished his dominance to a younger countryman, Sebastian Vitzthum. Then another Austrian, Hans Hofer, won his first title.

In 1996, Rogers and his new partner, Bill Flavin, sold the tour to Del Wilber & Associates from McLean, Virginia. Calling it the World Pro Ski Tour, Del Wilber soon had it up for sale again. One potential buyer, ESPN, gave it a pass to start the X-Games instead, and another, IMG, also let it go, leaving the field to the Fox Family Channel which, within two years, cancelled all of its sports programming.

“When Chrysler left, we couldn’t find a replacement,” says Rogers. “Fox couldn’t come up with enough sponsorship either, and that’s what pro sports is all about.” The sad irony, Rogers says, is that pro racing, which had been running continuously in the United States for nearly 40 years, came apart at a high point, with high-profile racers and record prize dollars.

“I think I know how it could work again,” says the plain-talking Rogers, now in his 70s, “but I’m not about to do it. I put in my time.”

Look for an account of the women’s pro tour in the July-August issue, by former U.S. Ski Team and pro racer Lisa Densmore. In the September-October issue, we’ll publish a look back at the Bee Hive, a professional giant slalom race that flourished in the early 1960s at the Georgian Peaks ski area in Ontario, Canada.