Early boot design was dictated by binding design. The modern era introduced new materials, fit and height that led to a revolution in alpine technique.

BY SETH MASIA

In the beginning, Norwegian farmers and hunters used their daily work shoes when skiing. Until the 1840s, the typical ski binding was a simple leather strap that passed across the front of the boot. The main design concern was to keep the inside of the boot dry, so the socks could do their job of insulating the foot. Water repellency depended on tough top-grain leather liberally slathered with a mixture of wax and animal fat. This combination of a flexible boot, simple binding, and skis without steel edges was useful mainly for running across meadows and gently rolling woodland, and an occasional sporting ski jump. The simple forefoot strap imposed a limit on running performance: If the skier kicked back too briskly, the boot could slip backward out of the strap. Saami skiers—the original Lapplanders—had a solution for this: They built a vertical lip onto the toe of their reindeer-hide boot, to keep it from sliding back through the binding strap. Sometimes this lip became an exaggerated curled-up toe; Santa’s elves are often depicted wearing Saami boots.

Polar Museum, Oxford

When skiing became a sport, and skiers began to tackle steeper hillsides and real jumps, skiers needed better control of both steering and edging. Bindings grew stiffer, with the invention around 1840 of the heel strap to pull the boot firmly forward into the toe strap. Sondre Norheim and his friends, for instance, devised a heel-strap binding of braided willow. When Fridtjof Nansen equipped his team for the 1888 crossing of Greenland, the Saami-style toe was still in use, but a buckle loop had been added to keep the heel strap in place.

The toe strap then evolved into the rigid steel toe iron, and the heel strap became more robust in order to push the boot firmly into the toe iron. These developments required a boot with a stiffer, heavier sole, usually reinforced with a wooden shank to resist crumpling under the forward pressure of the heel strap. The heavy sole was extended front and back to provide purchase for the toe iron and heel strap. Climbing boots of the era were made on a similar pattern to accommodate crampons, but had steel cleats or calks nailed to the soles for traction, which would have destroyed any wooden ski top in short order.

From village cobbler to mass production

Until the 1870s, all of these boots were handmade by local cobblers. Mass production of military boots, nailed and screwed together mechanically, became common in England during the Napoleonic Wars, and during America’s Civil War, Union troops were equipped with mass-produced boots made to the first-ever standard sizing system. These developments didn’t really affect ski boot design. Because climbers and skiers ordered their boots from someone they knew in the village, nearly all ski boots were, in fact, custom made—the cobbler measured your foot before starting work.

Goodyear welt

This changed with the introduction, in the United States, of industrial sewing machines and mass-produced shoes and boots. The key inventions were the Goodyear welt, developed beginning in 1865 by mechanics working for Charles Goodyear, Jr.; and the automatic lasting machine, patented in 1883 by Jan Matzeliger. The inventions were promptly put to work in New England’s mill towns. By 1876, the G.H. Bass boot factory in Portland, Maine, cranked out a thousand pairs of shoes and work boots every day. European shoe factories sprang up using the new industrial sewing equipment, and by 1885 companies in Switzerland, France, Germany, Great Britain and Italy shipped thousands of shoes and boots daily. Around the turn of the century, the first mass-produced leather ski boots appeared in sporting goods catalogs.

The first alpine boots

For a quarter century thereafter, the typical ski boot was just a lace-up work boot with a roomy box toe (to accommodate those wool socks) and an extended sole to mate with the heel-strap binding of the era. Then, in 1928, the Swiss ski racer Guido Reuge invented a cable binding designed to hold the heel down for alpine skiing. He named the binding after the Kandahar series of alpine ski races.

instep strap.

The powerful steel cable and front-throw adjuster cranked hard on the boot sole, which had to be stiffened considerably. At this point, alpine ski boot design diverged from nordic boots. Boots for cross-country racing and ski jumping needed a flexible sole. But because alpine racing didn’t require the boot to flex at the ball of the foot, the sole could be built with a stiff full-length shank. And because alpine skiers wanted the foot held firmly down on the ski, bootmakers created an instep strap. Coincidentally, 1928 was the year the mountaineer Rudolf Lettner invented the segmented steel edge for alpine skis. Suddenly, skis could be controlled on steep and icy faces—if your boots were stiff enough to drive the edges.

Most skiers used inexpensive mass-produced ski boots, but racers, instructors and wealthier sportsmen ordered their boots custom-made, from ski-town cobblers in the Alps. A few of these craftsmen, like Peter Limmer Sr., set up shop in America.

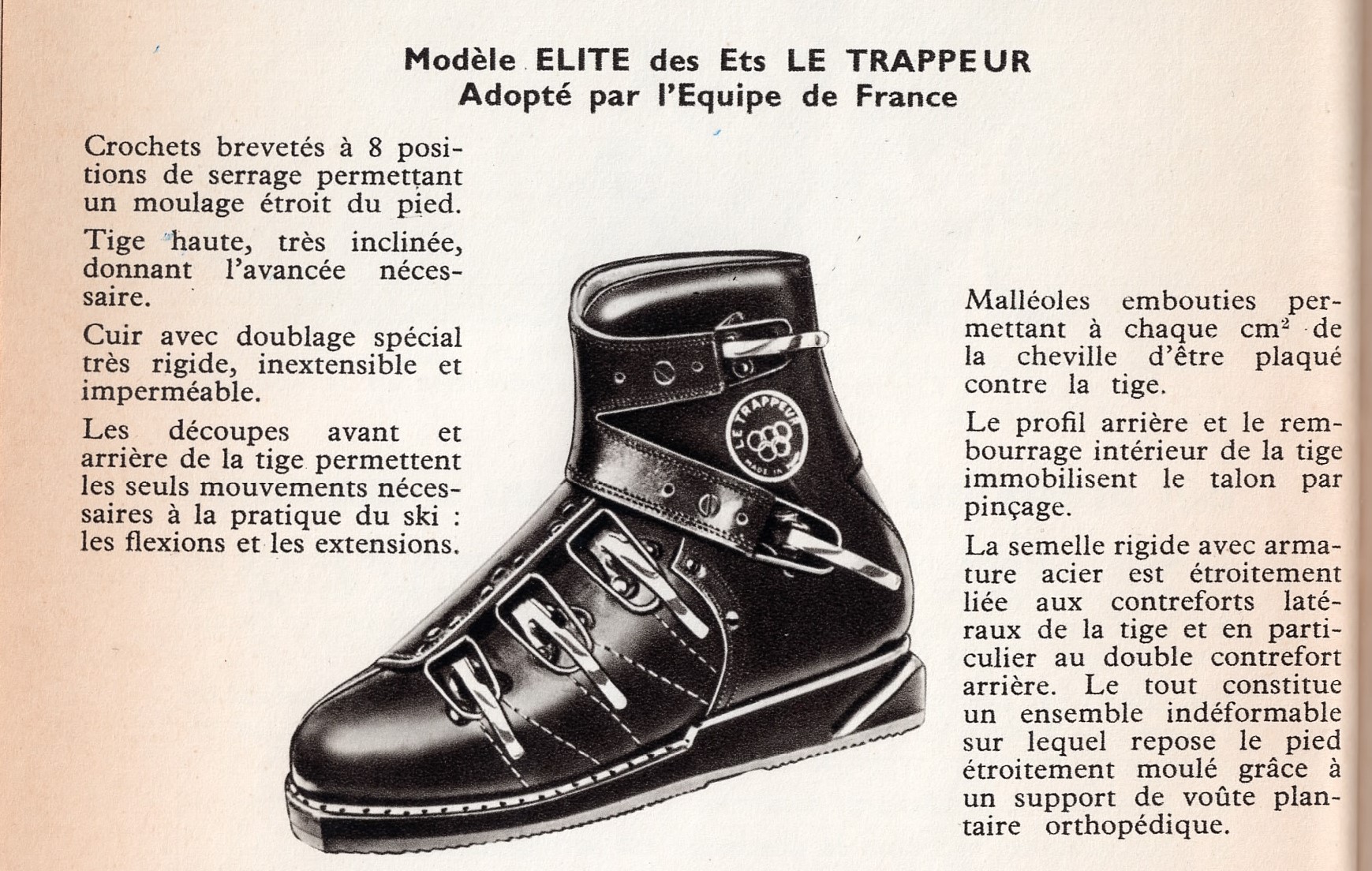

After World War II, custom bootmakers developed the double boot, with a soft and comfy lace-up inner boot protected and stiffened by a thick bull-hide outer casing laced with heavy-duty corset hooks. The complex design was difficult to reproduce with machines, and the European cottage industry adapted to mass production of hand-stitched leather boots. Companies like Henke in Switzerland, Le Trappeur in France and Nordica in Italy employed hundreds of workers to export hand-stitched boots.

With the commercialization of ski boots came the first serious marketing campaigns, and the first athlete endorsements. In 1950, when the Nordica shoe factory in Montebelluna, Italy, sold its first ski boots, the company had the good fortune to equip Zeno Colò, who won two World Championships at Aspen that winter. The publicity put Nordica on the map.

Even with several layers, leather boots were not very waterproof, warm or durable. If you skied more than a few days a year, boots quickly grew soft and sloppy. An aggressive skier needed new boots each winter, an expensive proposition. It was possible to soak leather in glue and make it stiff as a board, but then the boot couldn’t be laced closed, and wouldn’t adapt to the shape of the foot. Even reinforced boots got wet and softened steadily. Like many top racers, Jean-Claude Killy loaned boots to friends for breaking in. When the boots were “seasoned”—comfortable but not yet soft—they were good for a few races. Something better was needed.

Buckles and wedeln

A partial solution to making boots stiffer and more durable arrived in 1954, when Swiss bike racer and stunt pilot Hans Martin patented the ski boot buckle. His original patent specified a quick-adjust “lacing system” with overlapping boot flaps, to allow loosening for climbing and tightening for descents. Martin licensed the patent to Henke, and went to work helping to design their boots. The buckle was far more powerful than any set of laces and could close a very stiff boot. Quick, short turns became possible, and the tail-wagging wedeln technique became popular in ski schools around the world. To make boots even stiffer, bootmakers added internal plastic heel cups and cuff reinforcements.

Plastics and edging power

Then, during the half-decade from 1966 to 1972, everything changed. By 1962, European bootmakers were experimenting with sheets of plastic laminated to the outer leather for waterproofing and improved durability. At the same time, Bob Lange and Dave Luensmann made the first vacuum-molded plastic boot shell, and the following year figured out how to mold it from liquid urethane (see “50 Years of Lange” in the March-April 2015 issue of Skiing History). Nordica’s Aldo Vaccari—a chemical engineer by training—saw the Lange boot and quickly figured out how to replace

hand-stitching of the leather sole with a waterproof polyurethane outsole, permanently bonded to the leather upper, using high-speed injection molding machinery. This was a big improvement, quickly adopted by competing factories. It superseded eighty years of lasting machinery based on sewing-machine technology.

But the real revolution occurred in 1966, when Lange equipped the Canadian ski team with plastic boots for the Alpine World Championships in Portillo (see “Fifty Years of Lange,” March-April 2015). The boots were a sensation—it quickly became clear that laterally stiff plastic boots dramatically improved edging power on ice, and that they would eventually dominate racing. At the 1968 Olympics, Jean-Claude Killy won four gold medals in his fiberglass-reinforced leather Le Trappeur Elite boots (including the FIS Combined championship), and his French teammates won six more, all in leather boots. Only five of 24 medals were won in plastic Langes (by Nancy Greene and Heini Messner), and one or two in the fiberglass Raichle, but the handwriting was on the wall. Leather boots soon disappeared from racing. Nordica introduced its first all-plastic boot that year. Neighboring boot factories in Montebelluna rushed to make “plastic” boots with urethane-coated leather. By the following year full-bore injection-molded boots were available from Kastinger and Peter Kennedy, Rosemount was shipping its fiberglass boot, and Mel Dalebout offered a magnesium shell.

Spoilers and avalement

Meanwhile, French racers developed a new technique using knee flex to absorb or “swallow” the cross-under portion of turn initiation. This was dubbed avalement, French for swallowing. The move demanded full use of the ski tail in powering the turn exit, and that required a higher boot back. In 1961, Le Trappeur introduced the Elite (See Le Trappeur Elite), a stiff, forward-canted boot that gave racers a better tool for knee-flexed pressure control, and it was widely imitated by Nordica, Heierling, Heschung and other factories. In 1966, Canadian Dave Jacobs told Bob Lange to make the Lange Comp ski like the Trappeur. Before the 1972 Sapporo Olympics, “spoilers” appeared on racing boots, including the stovepipe Lange Comp and sleek leather Nordica Sapporo and plastic Olympic, designed by Sven Coomer (see

“Master Boot Laster,” May-June 2014). By 1973, driven mainly by Coomer at Nordica, the fully modern ski boot had emerged, with its removable and customizable innerboot, overlap or external-tongue closure, and hinged cuff with a high-back spoiler. The Nordica Grand Prix became the model for almost all high-performance boots to follow. Plastic boots didn’t break in like leather, and required “flow” materials or some form of adaptable or injected foam to conform comfortably to the infinite variety of foot shapes.

There were significant departures from this model: the warm and comfortable rear entry boot, first sold by Freyrie, Montan and Heschung in 1968, had a good run beginning with Hanson in 1971, and accounted for 80 percent of all boots sold by 1987 (see The Rear Entry Boot).. But racers weren’t impressed, preferring the closer shell-to-foot fit of overlap designs. Most factories kept a few overlap race models in production, and by 1990 most high-performance boots returned to that model. In 1980, half a dozen factories introduced innovative knee-high boots, which proved both comfortable and powerful—but the ski pants of the era didn’t fit over the tops, so ski shops quit selling them after a year.

There were also some design improvements. A huge step forward came when ski boot sole shapes standardized in the 1970s. It meant that ski bindings finally had a reliably consistent mechanical surface to grasp. Driven by international standard-setting organizations, binding design consolidated around a well-understood set of engineering principles, and the rate of lower-leg injuries dropped by 90 percent.

In the late ‘70s, Mel Dalebout invented the detachable and cantable outsole. Sven Coomer developed the custom-fit “orthotic” insole to improve power, comfort and precision in any boot, and then, in 1983, working for Koflach, he introduced the power strap, which had the effect of a fifth buckle at the top, bringing the effective tongue height to mid-shin. Henke introduced the three-piece shell (“bathtub” lower shell, external tongue, upper cuff) with the Strato in 1971, and the concept took off with the introduction of Nordica’s Comp 3 (1978) and Raichle's Flexon (1980) (see Origin of the Three-piece boot). That Raichle is still in production under K2’s Full Tilt brand. Over the decades, several attempts were made to popularize soft and comfortable “walking” boots that could slip into a supportive exoskeleton for skiing (Ramer, Bataille, Nava). Denny Hanson finally made it work with the new Apex brand.

And that’s where we stand.

As technical editor of SKI Magazine for 20 years, Seth Masia witnessed much of the modern evolution of ski equipment. He wishes to thank Gary Neptune for providing sample boots for photography, from the Neptune Mountaineering collection.