The first “safety” bindings, by Portland skier Hjalmar Hvam, weren’t all that safe. But 50 years ago, Cubco, Miller, Look and Marker began to change skiing’s broken leg image.

By Seth Masia

(First published in Skiing History, September 2002)

By the mid-Thirties, half of the great inventions of alpine skiing were already in place. The standard waisted and cambered shape for a turning ski had been established 80 years earlier by Sondre Norheim. Rudolph Lettner had introduced the steel edge in 1928, and the first laminated skis – with ash tops and hard bases of hickory or even Bakelite plastic – were produced in 1932. The Eriksen toe iron and Kandahar heel cable assured a solid connection of boot to ski.

Too solid. Every racer could count on breaking a leg from time to time, and some of the classic European downhills hospitalized up to a third of the entry list. Around 1937 a small company in Megeve, Reussner-Beckert, introduced a primitive adjustalble-release toe iron. The Ski Club of Great Britain liked it enough to offer a 25 pound prize for the best "safety" binding produced in the coming year. The winning entry, from one P. Schwarze of St. Gallen, Switzerland, provided that if the boot sprang free of the heel cable, the toe would also release -- but upward, not laterally.

Some of the brighter lights in the skiing community experimented with homemade release systems. One of these brighter lights – and one of the injured racers – was an elegantly tall, slim athlete named Hjalmar Hvam. Like Mikkel Hemmestveit and countless Norwegians before him, Hvam was a great Nordic champion who emigrated to the U.S. Born in Kongsberg in 1902, Hvam won his first jumping contest at age 12, and won consistently through his teens. But he jumped in the shadow of the local Ruud brothers – Birger, Sigmund and Asbjorn – who snapped up all of the Kongsberg team slots at the annual Holmenkollen classic.

Hvam quit skiing and emigrated to Canada in 1923, arriving in Portland in 1927. He worked as a laborer in a lumber mill until joining the Cascade Ski Club in 1929. He was quickly recognized as a leading jumper, cross-country racer and speed skater, peaking at the national championships in 1932 at Lake Tahoe, where he won both the jumping and cross-country events to take the Nordic combined championship. Coaxed onto alpine skis, he won both runs of his very first slalom race, in 1933 – the Oregon state championships. On borrowed skis.

That experience led to twelve consecutive downhill victories in 1935 and 1936, including the Silver Skis on Mt. Rainier and the first running of the Golden Rose race on Mt. Hood. On Mt. Baker, in 1936, he won a four-way competition with victories in all four disciplines – jumping, cross-country, slalom and downhill. He qualified for the U.S. Olympic Team that year, but couldn’t compete because he was still a citizen of Norway.

In 1935, he opened the Hjalmar Hvam Ski Shop in Northwest Portland, with a branch at Mt. Hood. The city shop had a great location, right on the 23rd St. trolley line from downtown. Hvam saw firsthand the dozens of injuries suffered by his customers, as well as by competing racers. No one kept national records, but it appears that the injury rate was horrendous. Ski injury experts like Dr. Jasper Shealy and Carl Ettlinger estimate that in the years just before and after World War II, about 1 percent of skiers suffered an injury on any given day – so it’s likely that by season’s end, 10 percent of all skiers were out of commission. About half of these injuries were probably lower-leg fractures. The most visible après-ski accessories were plaster casts and crutches. It wasn’t a recipe for long-term commercial success.

Trained as a mechanical drafstman, Hvam began tinkering with toe irons, looking for a reliable way to release the boot in a fall. The problem then, as now, was how to make a sophisticated latch that would hold a skier in for normal skiing maneuvers – steering, edging, jumping, landing – but release in abnormal or complex falls. It was a puzzle.

Injury Leads to Invention

Hvam’s “Eureka!” moment came under the influence of a powerful anaesthetic. In June 1937, Hvam won the Golden Rose on Mt. Hood – again – and then climbed with some friends to do a little cornice jumping. The result was predictable: In the spring snow, someone was bound to punch through the crust and break a leg. This time, it was Hvam, and he sustained a spiral fracture. He was sent to Portland’s St. Vincent Hospital for surgery. “When I came out of the ether I called the nurse for a pencil and paper,” he wrote decades later. “I had awakened with the complete principle of a release toe iron.”

What he imagined looked like a simple pivoting clip notched into the boot’s sole flange. An internal mechanism held the pivot centered as long as the boot toe pressed upward against the clip. But when that pressure was removed, as in a severe forward lean, the clip was freed to swing sideways. Thus Hvam provided for sideways toe release in a forward-leaning, twisting fall.

In 1939, Hvam broke the leg again, this time while testing his own binding. He always claimed the leg had never healed properly, but it did teach the lesson that “safety” bindings aren’t always safe. Nonetheless, Hvam launched his Saf-Ski binding into the market. His release toe was received with enthusiasm by his racing and jumping friends. Jumpers used it by inserting a heel lift under the boot, thus jamming the toe iron so it couldn’t swivel. It seemed a pointless exercise, but professional jumpers from the Northwest wanted to support their friend.

Many racers viewed the idea of a release toe with intense suspicion, especially after Olaf Rodegaard released from his Hvam binding in a giant slalom. Rodegaard, however, was convinced that the release saved his leg, and kept the binding. Hvam sold a few dozen pairs before World War II broke out, and tried to talk the Pentagon into buying the toe for the 10th Mountain Division – but the troops shipped out before he could close a deal. At least three pairs of Saf-Ski toe irons went to Italy with the division, bootlegged by Rodegaard and by the Idaho brothers Leon and Don Goodman (the Goodmans would introduce their own release binding in 1952). Thus the first production release bindings found their way to Europe, screwed solidly to GI Northland and Groswold skis.

After the war, Hvam produced the binding in several versions for retail sale and rental. It was widely accepted by his buddies in the jumping and racing communities, at least in the West. He sold 2,500 pairs in 1946-47, and watched as a dozen North American companies rapidly imitated the principle. His new competitors included Anderson & Thompson, Dovre, Northland, Gresvig, Krystal , U.S. Star and O-U.

Euros Develop Release Systems

There were also European inventions. In 1948, in Nevers, France, sporting goods manufacturer Jean Beyl built a plate binding mortised into the ski. There’s no evidence that Beyl was inspired by American toe irons, and his binding was based on a completely different principle. It didn’t release the boot in a fall – instead, it swiveled to protect the lower leg against twist, without actually detaching from the ski. It did something no other binding could do: It would absorb momentary shock and return to center. The binding’s lateral elasticity was a revolutionary idea and it wouldn’t be duplicated by other manufacturers for another two decades. The plate also eliminated the flexible leather ski boot sole from the release mechanism, vastly improving reliability. Beyl wanted to give the product an American-sounding name, and settled on the title of a glossy weekly picture magazine published in New York. By 1950 Beyl had talked several members of the French team into using his Look plate, including world champions Henri Oreiller and James Couttet.

Norm Macleod, one of the partners in the U.S. importing firm Beconta, recalls that the problems with the Look plate were weight and thickness. To install the binding, a mechanic had to carve a long, deep hole in the top of the ski. “The plate was mortised into the top of the ski and therefore the ski had to be thick,” Macleod says. “It was set about a centimeter into the ski, and stuck up another 6 or 7 millimeters above the top surface. There was resistance to that. Racers thought it was advantageous to be closer to the ski.”

So in 1950 Beyl created the Look Nevada toe, the first recognizably modern binding design, with a long spring-loaded piston to provide plenty of lateral elasticity for shock absorption. Beyl was a perfectionist; in an era when most bindings were made of stamped steel, his Nevada was made of expensive, heavy cast aluminum. It was nearly bulletproof. It was a two-pivot toe unit-that is, the main pivoting body carried along a second pivot on which was mounted the toe cup, thus assuring that the toe cup would travel in parallel with the boot toe.

Hannes Marker, a native of Berlin who had learned to ski as a Wehrmacht soldier stationed in Norway, went to Garmisch after the war and found a job as a civilian ski instructor for the U.S. Army recreational center, where Leon Goodman was supervisor of the ski school. There he saw the American-made release toes, and thought “I can do better.” In 1952 he introduced his Duplex toe, a two-piece toe that gripped the corners of the boot toe flange in much the same way future pincer bindings would work. He followed this, in 1953, with the Simplex. Like the Look toe, and unlike the Hvam, it was adjustable for release tension, and was the first release toe to be widely accepted by racers outside France. And like the Look Nevada, the Simplex was a double-pivot system.

Cubberley Attacks Heel Release

Other tinkerers were hard at work. Beginning in 1948, in Nutley, N.J., mechanical engineer and recreational skier Mitch Cubberley brought an ingenious mind to the problem of skiing’s broken-leg image. Skiing with his friend Joe Powers at Highmount, Belleayre and Bromley, Cubberley concluded that a key problem – thus far addressed by no one – was unreliable heel release, arising from the combination of the soft leather boot sole, the longthong wrap used to reinforce the sloppy leather boot cuff, and the complex, serpentine Kandahar heel cable. He figured out how to eliminate the heel cable and its grip on the soft leather sole, designing an elegant spring-controlled latch which could be mounted at both toe and heel.

A key element of the Cubberley design was the boot plate. Steel plates were screwed solidly to the toe and heel of the boot, and the spring-loaded binding gripped these plates rather than a soft, wet, flexible boot sole. The metal-to-metal contact provided more consistent release and reduced boot-to-ski friction. Cubberley sold about 200 sets during the winter of 1949-50. In Orem, Utah, Earl Miller was on a parallel track, and a bitter rivalry grew between the two men.

In Annecy, France, Georges Salomon, manufacturer of steel ski edges and cable heel bindings, produced his own release toe, the Skade, to sell with his popular Lift cable heel. It was neither a single-pivot design, like the Look, nor a two-pivot toe, like the Marker, but instead used a pair of roller bearings, riding on a steel cam, to guide the toe cup in its lateral travel. It was a less elegant system, but it worked, and Salomon signed up a roster of ski racers to endorse it. The basic design, beefed up with more substantial castings, eventually produced the best-selling S.444 and S.555 bindings.

In 1952, Mitch Cubberley patented a toe unit that would release in all directions, and sales took off. By 1955 he’d added a lip to his heel latch and created the first step-in heel. Earl Miller dubbed his own binding the Hanson. He spent several winters promoting the binding by throwing himself into terrifying tumbles to demonstrate its release.

Back in Portland, Hvam kept cranking out a few thousand pairs of Saf-Ski toes each year. In 1952, at age 50, he coached the U.S. Nordic Combined team at Holmenkollen – and found he could still outjump most of his young athletes. His ad agency created the slogan “Hvoom with Hvam – and have no fear!” Magazine ads featured a photo of Hvam soaring through a gelandesprung jump, accompanied by a chatty text in which Hvam explained, in Norwegian-English syntax, how his binding worked. “Maybe you do not know about release bindings,” read one ad. “Maybe you are in a hospital with a broken leg. . . . Let me tell you about how the Hvam toe release works. It never releases while you ski, because this part has two rounded pins that fit into sockets and it cannot swivel because this part is pushed upwards. As long as it pushes up, it cannot swivel. When you ski, your boot sole always pushes up on the toe release lip. The harder you edge, the harder your toe is locked in place. Now. When you fall bad, your foot may twist. Your foot twists sideways, there is not much pressure up. The toe swivels, and your boot may be twisted out without injury. Maybe you think I would tell you a lie. If you think so, I am sorry for you. I would not lie about anything. Especially I would not lie about skiing, because skiing is what my whole life is about.”

By 1953, with the widespread adoption of “safety” bindings, it became disconcertingly clear that the injury rate wasn’t improving. The Stowe ski patrol reported that they were still transporting about four leg fractures per 1000 skier days, and placed the blame on the fact that there was no standard method of adjusting and testing release bindings. In France, in 1954, Jean Beyl offered a $71 indemnity for any broken leg suffered using a factory-mounted Look-and paid out only twice based on 1,180 skiers. Ski Magazine estimated that this amounted to an injury rate of .17 per 1,000 skier days-which presumably meant you’d be 24 times safer skiing on a properly adjusted Look than on the average New Englander’s recreational rig. Earl Miller responded the following winter by offering his own $100 bounty for broken legs suffered on Hanson bindings mounted in his own Provo shop.

Release Toes Proliferate

By the late 1950s, American ski shops were selling release toes under some 35 brand names, including A&T, ABC, Alta, Aspen, Attenhofer, Cervin, Cober, Cubco, Cortina, Dovre, Eckel, Evernew, Geze, Gresvig, Goodman, Gripon, Kenny K, Krystal, Look, Marker, Meergans, Miller, Northland, O-U, P&M, Persenico, Ramy, Ski-Flete, Ski Free, Spearhead, Stowe Flexible, Suwe, Top, Tyrolia, U.S. Star and Werner. Hvam kept his prices low – in 1961, when the Look Nevada toe sold for $12.50, Hvam’s Standard model, in chrome, retailed for $6.95 (though there was a Deluxe model, in gold, for $12.50). Hvam introduced his heel release cable for $4.50, when the Look cable sold for $7.50.

Other than Cubco and Miller, no one else had yet figured out how to eliminate the heel cable, essentially unchanged from Reuge’s 1932 Kandahar design. Because cable heels were generic, it was common to see mixed systems: You could mount a Hvam toe with a Salomon Lift cable, or a Look toe with a Marker turntable. As late as 1965, Marker was still selling a non-release sidethrow turntable heel. At this point, Look introduced the releaseable Grand Prix heel, based on the same high-elasticity principle as the Nevada toe unit.

Hvam’s binding was already obsolete, and while Cubco’s system worked efficiently, it was viewed with disdain by experts, who distrusted upward toe release.

In 1961, rivals Earl Miller and Mitch Cubberley introduced the first ski brakes, eliminating the “safety” strap and with it cuts and contusions due to windmilling skis. Ski resorts wouldn’t accept ski brakes until the major European binding brands adopted them beginning in 1976.

On the racing side, momentum was moving steadily in favor of the European factories, which had access to the top racers. Stein Eriksen, for instance, endorsed Marker, and in 1960 Jean Vuarnet and Roger Staub won gold medals at the Squaw Valley Olympics using the Look Nevada I toe. Look got another promotional boost when Karl Schranz and Egon Zimmermann switched from Marker.

Rocket science

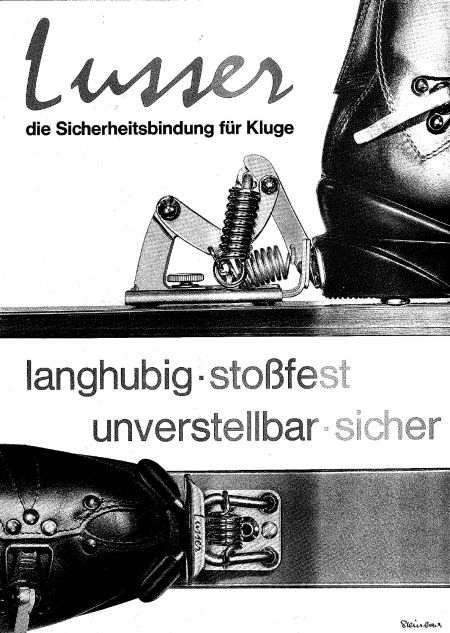

The ski binding market was about to change. In 1961, a real rocket scientist named Robert Lusser ruptured his achilles tendon while testing his own cable bindings in his hotel room at Saas-Fee. A champion aerobatic pilot and designer of Klemm light aircraft, Lusser went on to design German fighters for Messerschmitt and Heinkel during WWII. At Heinkel he was responsible for the first jet fighter that ever flew, and had created the Fieseler V-1 “buzz bomb.” The U.S. Navy grabbed him in 1948 to work on early cruise missiles at Point Mugu, California, and he did some work for Wernher von Braun on the Redstone missile project, before returning to Germany, and Messerschmitt, in 1957.

Lusser did a thorough engineering analysis of the binding release problem, and came up with three key innovations: A teflon anti-friction pad under the boot toe, a heel release system based on a heel cup, a cam and a fixed-tension spring, and a simple toe unit that gripped the upper radius of the boot toe instead of the toe flange. This last innovation provided a long high-elasticity stroke before release, which meant that the binding could return to center without releasing — even at relatively low spring tension settings. It was an ugly toe, built like a Cubco spring turned sideways and linked to a couple of steel-wire boot-grippers. But it worked.

Lusser did a thorough engineering analysis of the binding release problem, and came up with three key innovations: A teflon anti-friction pad under the boot toe, a heel release system based on a heel cup, a cam and a fixed-tension spring, and a simple toe unit that gripped the upper radius of the boot toe instead of the toe flange. This last innovation provided a long high-elasticity stroke before release, which meant that the binding could return to center without releasing — even at relatively low spring tension settings. It was an ugly toe, built like a Cubco spring turned sideways and linked to a couple of steel-wire boot-grippers. But it worked.

Lusser patented these inventions, and the major binding companies picked up his innovations. At Look, Jean Beyl redesigned the two-pivot Nevada toe. The result, in 1962, was the ingenious single-pivot Look Nevada II, with its long toe wings that gripped the boot’s upper toe, rather than the sole flange. This patented design remained the basis of Look toe units for the next 40 years.

In 1963 Lusser quit his job at Messerschmitt and launched the Lusser binding company. He died in 1969, and the brand died with him. But he had started the ball rolling on his three key breakthroughs.

During the Sixties, Mitch Cubberley and Gordon Lipe proved the importance of reducing boot-ski friction, and, in parallel with Lusser, created the first anti-friction devices. Personal injury attorneys began paying closer attention to ski binding design. Cubberley had the test results to prove that removing the leather boot sole from the release system improved safety, and by the mid-Sixties Cubco was selling more than 200,000 sets of bindings annually. Cubco was the binding of choice for rental operators.

With his dated design, Hvam had a problem. In 1966, his insurers wanted a $160,000 liability premium. He would have had to sell nearly 120,000 sets of toes just to pay for insurance, and he had nowhere near that kind of market share.

Standardized Sole

Technology was advancing on other fronts. Look had introduced the Nevada II toe, following Lusser’s idea of gripping the upper radius of the boot toe. The company aggressively, and correctly, promoted the value of high elasticity and shock absorption, and the message got through. As racers talked about “Markering out” of the Simplex, European factories redesigned their toes for longer travel, producing products like the Marker M4 and Geze Jet Set on Lusser’s patents.

In 1967 Tyrolia introduced the Clix Rocket step-in heel unit, and Salomon responded with a heel unit that could be cocked open for step-in by closing its cover latch. By 1970, Kurt von Besser, Rudi Gertsch and Dr. Richard Spademan introduced new variations on the plate binding, just as plastic boots offered the promise of a standardized boot sole, which would eliminate the need for notched toes and screwed-on steel plates. It was clear that to stay competitive, a ski binding company needed deep pockets for research and testing.

On the commercial side, the big European factories found sizeable American corporations to distribute their products in North America. Beconta commanded almost 30 percent of the market for Look, while Garcia Corp. – distributor of Fischer and Rossignol – hawked Marker even more successfully. Salomon found a home at A&T. Tyrolia was purchased by AMF. Tiny independent companies like Hvam, Cubco and Miller began to look irrelevant in the great merchandising wars. Even smaller start-ups – Americana, Moog, Allsop – muddied the waters and cut into market share.

Saf-Ski R.I.P.

In 1972, Hvam retired and the Saf-Ski binding disappeared for good. Hvam died in 1996 at the age of 93. Hvam never fully solved the problem of pre-release, or heel release, or boot sole flex, but he defined the issues and led the way.

Cubco, armed with brilliant reviews from the testing labs, soldiered on. Mitch Cubberley was determined to build a safe, effective and cheap binding, and seemed equally determined to keep it ugly. With the universal adoption of standard plastic boot soles, his binding lost its performance advantage. Thanks largely to his own efforts in partnership with Gordon Lipe to eliminate boot-to-ski friction, industry-wide injury rates fell 75 percent to about 2.5 sled rides per thousand skier days, and most of those injuries were upper-body fractures entirely unrelated to ski binding issues.

Moreover, Cubberley was amazingly generous about his own designs. When other companies infringed on his patents-the original Gertsch plate and the Rosemount toe unit are egregious examples-he declined to protect his rights. Cubco, a victim of its own technological leadership, slid into commercial obscurity.

Cubberley, more than anyone the man responsible for destroying the sport’s broken-leg image in North America, died in 1977 at age 62. Cubco folded two years later. But the truth is, if you have a late-model Cubco binding, complete with its standard Lipe Slider, it still works pretty well.

By 1976, when Look’s single-pivot patent expired, Salomon was ready to adopt its long-elasticity design with the first of the 727-series bindings. Even so, the Look Nevada toe of the era featured almost twice the elastic travel of the 727, or of any other toe unit available at the time.

Thanks largely to the work of Jean Beyl, Robert Lusser, Mitch Cubberley and Gordon Lipe, today’s bindings – with long-elasticity toe and heel units, anti-friction devices, and standardized boot soles – have reduced lower leg injuries to an insignificant level, while largely eliminating pre-release. The complex issue of knee injuries is another matter, which we may well revisit in these pages in years to come – if new binding designs succcessfully address it, and new pioneers step up to the plate.

Photos: Top of page, Cubco step-in; middle of page, Robert Lusser's low-friction, high-elasticity ski binding.