Can Vail Resorts improve employee and customer relations?

By Seth Masia

From the January-February 2022 issue

(Posted February 12, 2022) Overcrowding and staff shortages at ski resorts first attracted the attention of local and online media at the end of 2021, then in January spread to traditional outlets like the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, statewide papers like the Denver Post and Seattle Times, and special interest magazines such as Outside.

To be fair, resorts faced the same issues as businesses in general: namely labor shortages and slow delivery of inventory. When a shortage-afflicted business takes payment up front, fulfillment and customer services deteriorate. Late delivery angers customers.

That’s what happened at ski resorts this winter. Covid accelerated and exposed long-term trends, creating a perfect storm of employee and customer angst. A booming real estate market and an increase in Airbnb-type short-term rentals pushed the housing shortage from chronic to acute, which, combined with decades of static wages, forced employees into onerous commutes. Many employees simply declined to work that way, and when Covid put remaining employees in isolation, there weren’t enough bodies to shovel or make snow, drive groomers, maintain equipment, bump lifts, patrol and teach, flip burgers, make beds, punch cash registers, fit rental boots and provide childcare. At the same time, skiing seemed a Covid-safe outdoor activity, season passes were cheap, and skier visits on peak days soared. Ski retailers sold out early, highways and parking lots jammed up, and skiers stood in 40-minute lift queues. Skiers tolerate the late arrival of natural snow, but when the snow is great and the lifts don’t turn, they fume.

Vail Resorts was a particular target of consumer fury, incurring an organized protest movement and threats of class-action lawsuits, beginning at Stevens Pass, Washington. There, more than 44,000 skiers signed an online petition calling VR responsible for failure to open lifts and terrain, and about 300 complaints went to Washington’s Attorney General Bob Ferguson. By late January a new general manager, Tom Fortune, was turning the corner, solving some of his staff issues and opening popular backside access. The fixes were simple: more efficient use of available employee housing, increased employee shuttle service and new hiring. VR also offered the resort’s passholders deep discounts to sign up for next winter, and promised to extend the season through April. It’s worth noting that Vail very publicly bumped its minimum wage to $15 per hour in the key states of Colorado, Utah, California and Washington—but in the pre-Covid era VR’s average hourly wage for its roughly 47,000 seasonal employees was around $12 per hour. In mid-January VR offered a $2-an-hour bonus for employees who stay on until the end of the season.

In recent years, VR has set itself up for local disaster. The universal Epic Pass was a huge boon to average skiers, and a tonic to investors; it has transformed the resort industry with one simple, game-changing mantra: Skiing will now be purchased in advance. Meanwhile, VR took steps to bolster the bottom line for shareholders, such as slashing middle-management salaries by centralizing most corporate functions at its Broomfield, Colorado headquarters. The unintended consequence is a corporation slow to react to emerging local problems. Off-site marketing and finance personnel are blind to the nuances of local markets, and local issues. But the bridge too far was the cutback in local human-resources personnel, and the consequent loss of on-site expertise in local recruiting tactics, transportation and housing issues. Payroll functions were moved to an app that didn’t work.

As part of VR’s campaign to maximize margin in every segment, it built retail, lodging, food service and transportation enterprises that compete with local businesses. Building employee housing is always difficult, but alienating prominent locals doesn’t help.

VR cut the price by 20 percent and sold more than 2.1 million Epic Passes last summer, up 76 percent from pre-Covid 2019. According to its December 9 quarterly report, the company sailed into the season holding $1.5 billion in cash. It can well afford to spend what’s needed to fix local problems. Those problems now include settling class-action lawsuits by employees, meeting obligations under new collective bargaining agreements—and fixing housing and transportation issues. While they’re at it, they need affordable learn-to-ski packages for first-timers who get the itch in January, and improved access to free or cheap parking.

The original Vail Associates, from opening day in 1962, set the gold standard for American skiing. Vail offered the best slope grooming in the world. It recruited a top-ranked ski school. Vail’s managers, many of them veterans of the 10th Mountain Division, promoted skiing culture, for example by enlisting well-known skiers like Pepi Gramshammer and Dave and Renie Gorsuch to establish businesses in town, and later, under George Gillett, by bringing the World Championships to town. When the private equity firm Apollo Partners took VR public in 1997, they did what Wall Street always does: managed for shareholder value rather than customer and employee morale. To skiers, it now looks like VR has been cannibalizing VA’s good will.

According to annual reports, in fiscal year 2019 (the last pre-Covid year), VR’s mountain-operations revenue was $1.9 billion, and company-wide gross profit margin (EBITDA) was 36 percent. The National Ski Areas Association Economic Analysis shows the average large North American ski resort EBITDA then at about 26 percent. The difference was not only Vail’s success in selling season passes, but in strict cost control. To solve the employee crunch and relieve skier crowding, VR may have to give back some of that margin. With its 25 percent market share (in skier visits), the sport needs VR to succeed.

Will spending that money affect the stock price? Some 95 percent of VR stock is held by institutional investors, who may not care much about employee and skier morale. Closely held resorts have more freedom of action, and they’ve shown it this season to the benefit of their guests, employees and the communities they operate in. The other major resort conglomerate, Alterra of the Ikon Pass, has from day one taken the decentralized path, ceding control to its individual resorts. Aspen in mid-February gave a $3-an-hour raise to every employee in the company.

Rob Katz, the change-agent who created both the Epic Pass and VR’s 44-resort empire, stepped down as CEO in the fall and is now executive chairman of the board. His handpicked successor, veteran Kirsten Lynch, the data-driven marketer who has brainstormed the Epic Pass metrics, is now in the hot seat. “One of the hallmarks of our company is agility and change,” Lynch told the Wall Street Journal in its January 15 story “Steep Slope for a Ski Empire.” By the time you read this, in March, we’ll have seen how agile VR can be.

Follow-up, March 14: Vail Resorts raises minimum wage to $20 an hour --Vail Daily

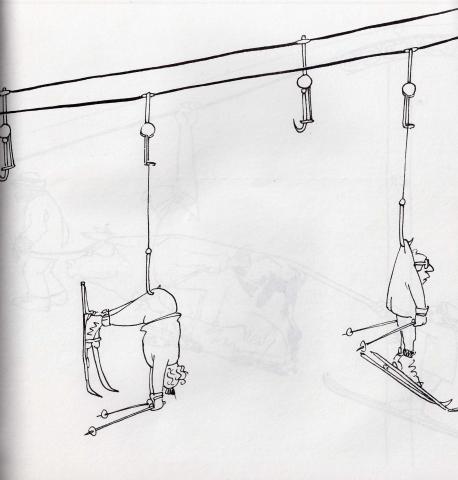

Image at top of page: Skiers on the hook, by Rudiger Fahrner

Comments

Good Article

Such a relief to read an article that is not biased, sticking to the facts and not having emotions do the writing.

Odd how that is so rare it needs to be recognized.

Vail resorts

This article is extreamly well written and documented. It expresses my frustrations as an Instructor, a Epic pass holder, and a sharholder.

I am acutely aware of the problems when I go to the Park City Mountain Resort - Canyons and the lack of expertise to deal will it.

A ski instructor does not make a good corporate manager and vice versa. The problem is corporate management is not involving, interacting, or listening to its employees as evidenced by all the lawsuits, negative press, and picketing.

There MUST be balance in all things. Those at Park City thought I was nuts when I spoke up about VailResort stock prices a few years back and were highly critical of me. I bought a substantial amount of stock and liquidated it in the past few months. I realized a 346% gain on my investment. So while they thought I was totally crazy I have had the last laugh.

The Disappointing Direction at Vail

As a 10th Mountain Division descendant and a long-time believer since my first visit in the 1970s that Vail Mountain is one of the most special places on the planet, it is hard to express the depth of my disappointment at what has gone wrong in recent years. Having spent a forty year career in the music industry watching the same, devastating trend, though, I have an inkling. The ski industry, like the music community, is based upon the absolute adoration of the buying public for the product. Both are "way of life" industries that cater to true believers in the sport and the art form. When that extremely positive market advantage is perverted into an invitation for corporate carpetbaggers to abuse the customer base, however, prompting abandonment of all forms of customer service in favor of exploitive practices designed solely to drive stock prices, very bad things happen. And tarnishing a platinum brand for short term profit, assuming all will be forgiven by a client base so loyal that its capacity for absorbing mistreatment is endless, is a very bad supposition. It's the mountain and its history we love, not the corporation. And if that is true at Vail, it is even more so at revered, historic and recently acquired venues including Stowe and White Pass. It is hoped that the Vail board and its "new" management keep that reality front of mind. We are all rooting for a reversal of attitude and performance to Vail's benefit. But it would be best to hurry.

Vail resorts

I understand that the bottom line must be watched. But not having enough workers at a ski resort to maintain facilities is not only bad business it is downright dangerous. Basic capitalist theory requires a company pay enough to maintain a minimum level of service at the mountain. In the East snow making is essential not only for the experience but ultimately to ensure a secure envirnonment. I am hearilty tired of companies looking only to the short term bottom line to give maxim return to investors. I certainly will be switching to the Indie Pass next year, to allow me to ski at resorts which keep skiers happy over investor profits.

VR

A rather prescient final sentence there Mr. Masia!

Vail is the Evil Empire of Skiing

I have read, with pleasure, this excellent account of the demise of Vail from an excellent ski resort at its inception into a money-grubbing corporation that epitomizes the worst aspects of rampant capitalism. I see that there have also been a few comments from others who I know and respect as longtime passionate skiers--Charlie Sanders and Chris Lizza. Most of us who are deeply involved in the ski industry have, for years, referred to Vail as the "evil empire"--the Darth Vader of the ski world, but it is only recently, that the general public has finally understood the truth. The Covid debacle was a sort of catalyst that created a situation whereby the longterm gross mismanagement of Vail's resources finally caught up with them to the extent that it was evident to most people in the general public. The golden rule of American capitalism is that all profit goes to the shareholders while the company tries to save money everywhere the can. This was well-described in the article. The cheap Epic Pass was a brilliant idea in bringing in tons of money, and considering the absurd prices of a walk-up-to-the-counter day pass, the Epic Pass seemed like an even bigger bargain. We who live in Europe and ski mostly in the Alps were extremely upset to see that the "evil empire" has managed to buy their way into their first Alpine resort, and we sincerely hope and pray that it will never happen again. Most Alpine resorts offer prices that are about 1/3 of a day pass to a Vail-owned resort and offer more terrain, better service, a mountain with restaurants that are privately owned by competing local entrpreneurs, a village that has family owned ski shops, hotels and restaurants, and a customer experience that is genuine. Basically, we can say that most European ski resorts have grown organically. As skiing began to take hold as a mainstream leisure activity in the years following World War II, the local farmers in Alpine villages shared in the growth of the sport. Some began renting rooms and soon were hoteliers. Others began selling lunches and dinners, while still others began teaching skiing or renting equipment. There was healthy competition and the villagers prospered together. Vail is a different proposal entirely. They take over an existing ma-and-pa resort and invest in some infrastructure while selling fancy condos and trophy homes. They monopolize as much as they can, like a greedy octopus in what ultimately is a real-estate investment more than it is a ski industry. In my books, Skiing Around the World Volumes I and II, I have included stories of my experiences in about 600 ski resorts in 75 countries. There are many stories and photos of obscure, remote, and little-known locations and of course, many chapters about the iconic resorts of the world. There is a very obvious ommission--I very consciously have not included a chapter about Vail.

Vail is out of the real estate game

Thanks for these comments, Jimmie. One correction: Vail no longer uses the sale of real estate as a profit center. I think they lost significantly in the real estate bust after 2008. I don't think they even have a real estate division any more.

Add new comment