SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Ron LeMaster, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

The European Origin of Skiing

Archaeology and DNA evidence support the theory that skiing arose east of the Baltic, at the end of the last Ice Age.

Translated by Seth Masia

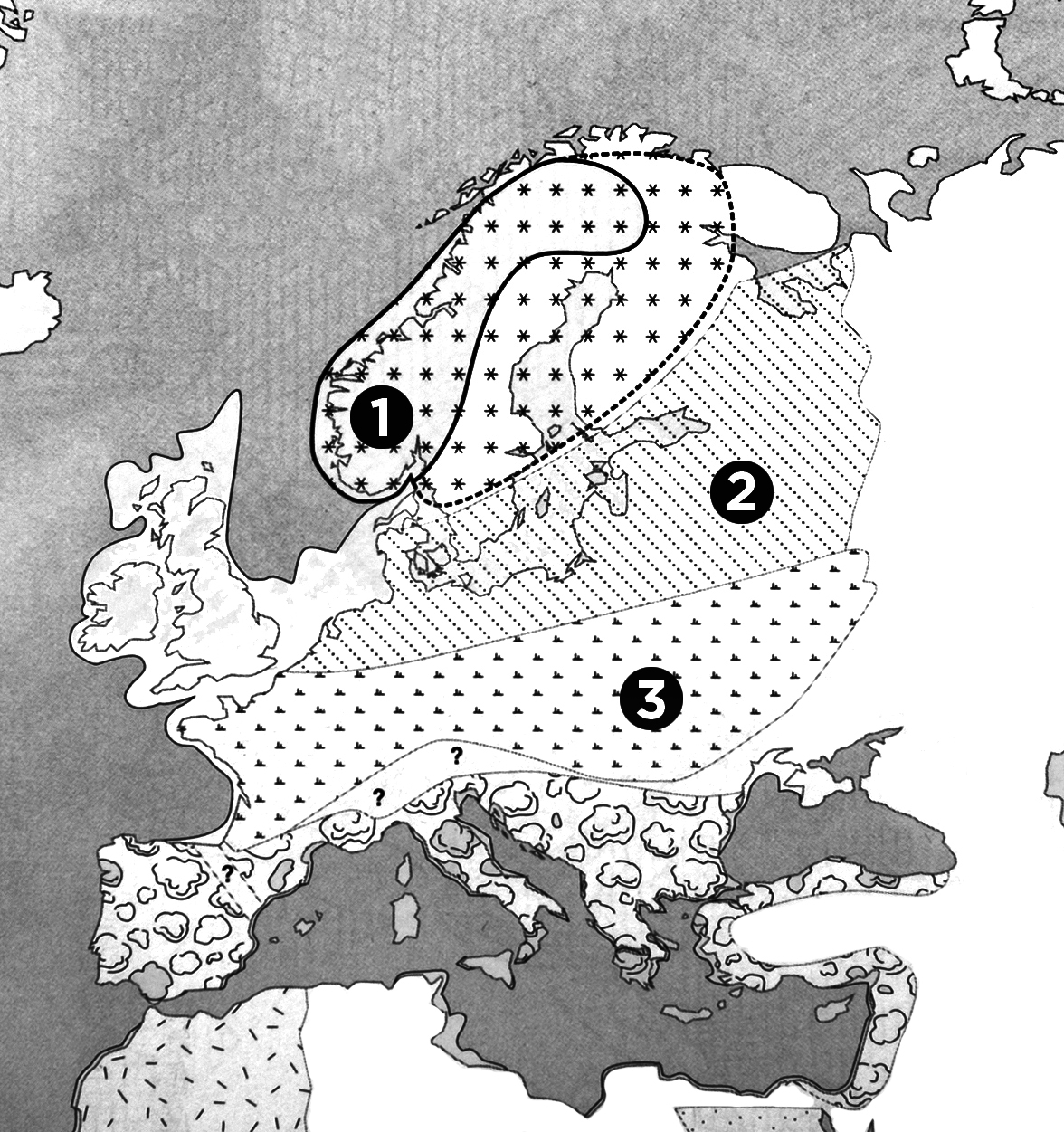

Photo above: The author proposes that skiing began between the Baltic and the Urals, in the gray oval containing all the archaeological sites that have yielded “fossil” skis. Skiing tribes then migrated north and west into Scandinavia, and eastward, up the Ob and Yenisei river valleys to the Altai region and beyond. Millennia later, the migration reversed, as Asian tribes moved west across the steppes and along the Arctic coast.

Where and when was skiing invented? In 1888, Fridtjof Nansen theorized that it was invented in prehistoric times in southern Siberia, in the region between Lake Baikal and the Altai Mountains. From there, he wrote, it spread with migrating tribes to the rest of Siberia and Europe. But archaeological sites in European Russia and recent DNA evidence suggest strongly that skiing began in the Baltic region, at the close of the last Ice Age.

While writing his book On Skis Across Greenland, Nansen asked his friend Andreas M. Hansen, a curator of the University Library in Christiania (today Oslo), to research the origin of the words for “ski” used by the peoples of northern Eurasia. This was probably the first linguistic study specific to skis. Nansen found Hansen’s report very curious. One surprise was to find the Finnish word suksi in much of Siberia.

In the middle of the 19th century, the Finnish linguist Matias Aleksanteri Castrén advanced the concept of a large Ural-Altaic language family, including the Finnish languages and languages spoken by the Tungus and Manchus, plus the Turks and Mongols. He located its birthplace in the Altai region. This concept could explain why the Samoyeds, who came from southern Siberia, spoke languages related to Finnish. The Ural-Altaic theory is now abandoned, but that was the dominant view in the 1880s and may have influenced the Hansen/Nansen linguistic theory.

Hansen reported that variations of the root word suk appear in the languages of the Baltic Finns and the Evenki peoples of Eastern Siberia and China, all the way to the Pacific. In Chapter Three of On Skis Across Greenland, Nansen wrote that both groups—along with the Samoyed tribes—originally were close neighbors in the Baikal-Altai region and migrated from there to the east, north and west. They traveled on skis and sleds. Nansen supposed that Scandinavian people learned to ski from Finns and Saami migrating from the east.

The Swedish historian and linguist Karl Wiklund (1868-1934) emphatically questioned the validity of Hansen’s study. The Norwegian linguistics professor Arnold Dalen, in 1996, did not reject Nansen’s hypothesis outright but found it most likely unverifiable. These reservations have not deterred wide repetition [of the Hansen/Nansen theory], and down the years the concept of a “Siberian cradle” is today set in stone.

covering Scandinavia (1), shrub-covered tundra (2) and a temperate belt of grassland and conifers (3). As the climate warmed, tribes migrated from the western and eastern ends of this region to create the Kunda culture south and east of the Baltic. Djindjian, Kozlowski, Otte.

(Translator’s note: In 1888, Hansen was a respected and influential geologist, but only an amateur philologist. His doctoral dissertation in geology focused on ancient shorelines and demonstrated that sea level rise and fall since the last Ice Age was a useful marker for determining the age of archaeological sites. He accurately placed the end of the last glaciation at between 11,000 and 9,000 years ago; and his ideas about the role of crustal “drift” were prescient. Nansen adopted Hansen’s geological ideas in his own studies of Greenland and Arctic geology. Hansen would go on to notoriety as an advocate of a racial theory of the Norwegian population that anticipated “Master Race” ideology.)

Origin of the Saami and Finns

According to Finnish anthropologist Markku Niskanen, Nansen’s contemporaries believed, on weak evidence, that Finnish-speaking Europeans, and especially Saami, were of Asian origin. Genetic studies have shown this to be wrong. Studies by geneticists Kristiina Tambets and Antonio Torroni show that the Saami come from the merger of two populations originating in Western and Eastern Europe. Specifically, the Saami are cousins of the Basques, merged with genes from the Proto-Finns of Eastern Europe. All Finns belong to European genotypes.

As Ice Age glaciers began to retreat during the warm Bølling–Allerød interstadial, about 15,000 to 13,000 years ago, tribes migrated north. One population left the ice-free Franco-Cantabrian region in the southwest [today’s Aquitaine and Basque country]. Another moved northwest from what is now Ukraine. The two groups met on the southern shore of the Gulf of Finland and around 10,000 years ago created the Kunda culture.

The Meaning of Migration

This is the starting point for Nansen’s error. He was correct to think that the word suksi had traveled between Siberia and Europe, but he was wrong about the direction it took. Archaeological and genetic evidence, consolidated in work by Russian expert Yakov A. Sher, now strongly suggests that the direction of migrations, from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age, was mainly from west to east, before reversing. Andrey Filchenko, of Nazarbayev University in Kazakhstan, mentions the presence in the Sayan region of ethnic groups of Finno-Ugrian origin, who came from northwestern Siberia and the Urals. They are known to historians as the Samoyed of the Sayan. The presence in southern Siberia of other Europoid populations prior to our era is otherwise firmly established.

The definite reversal of the direction of migration took place at the start of the Iron Age, when Asian nomadic hordes began to ravage the great Eurasian steppe that runs from Mongolia to the Carpathian Basin. The arrival of their avant-garde in Europe is dated by French archaeologist Michel Kazanski to the victory of the Huns over the Goths in the year 375. By this time, skiing had already existed in Europe for about 8,000 years.

(Translator’s note: Genomic research published in 2018 by Thisius Laminidis et. al. suggests that a Siberian migration entered the Saami/Finnish gene pool “at least 3,500 years ago.” By that time the Saami had been skiing for five millenia.)

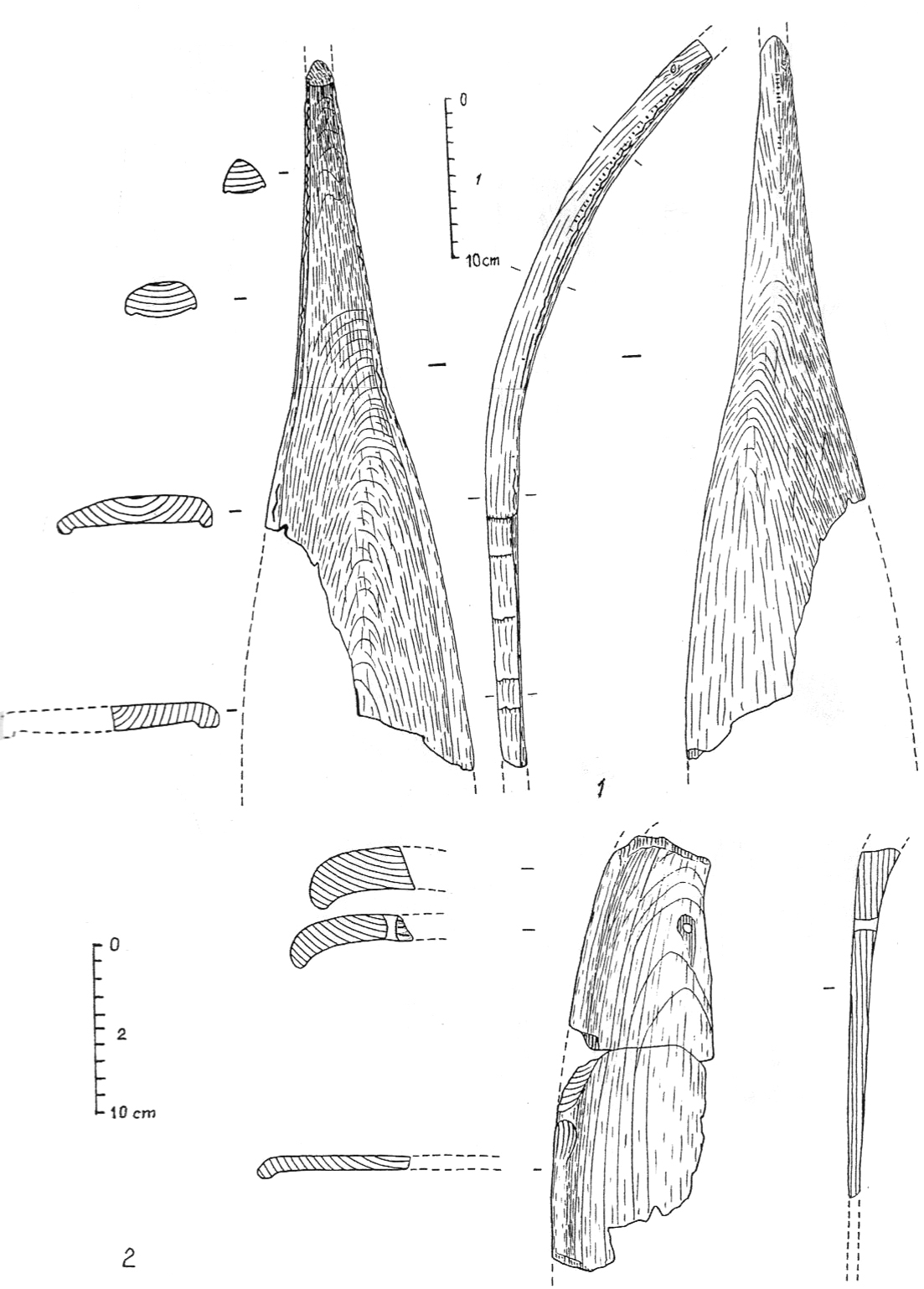

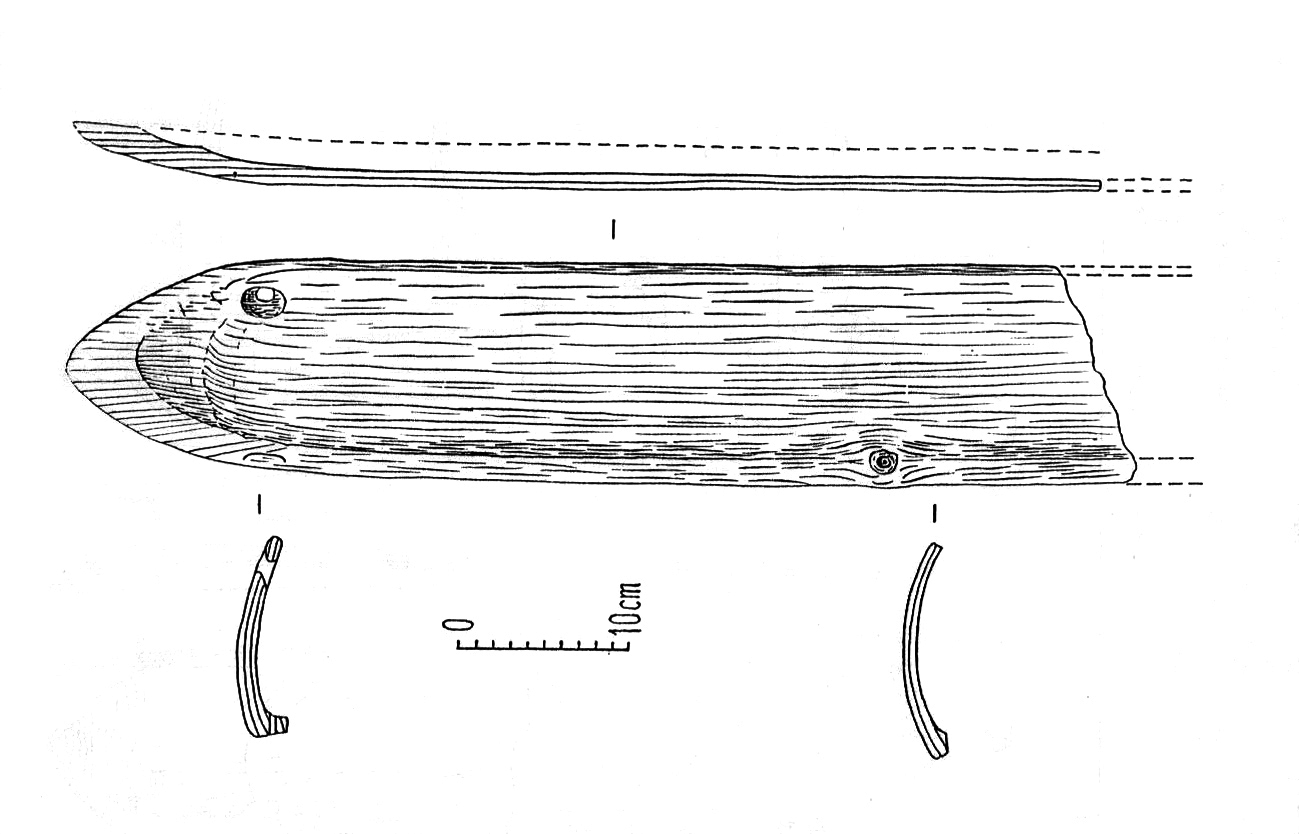

about 9,300 years old, at Vis in

1985. Carved from the trunk of

a tree, it was about 150mm

wide. Burov.

The Cradle of Skiing Is European

The arguments in favor of this thesis are archaeological, geographic and cultural.

The oldest skis we know of come from west of the Urals: from the Vis peatbog near Lake Sindor, 800 miles northeast of Moscow, and even farther west, from the Nizhneje Veretje site, 200 miles north of Moscow (the skis found here have been little studied but are of comparable age—about 9,250 years old). Archaeological finds, including sled runners, show that these two prehistoric settlements belonged to a larger group. According to Russian archaeologist Grigory Burov, who led the Vis digs, the culture “was probably linked to Baltic cultures (Suomusjärvi, Kunda) and to sites located between the Baltic and northeast Europe (Veretje).”

In addition, it’s very likely that skiing was practiced in southern Finland around 10,000 years ago. I asked Finnish archaeologist Hannu Takala and Grigory Burov for advice on this. Their response is quite clear: Takala wrote, “It is certain that the first settlers who came to Finland at least had wooden sleds since we have the Heinola sled [10,000 years old]. They probably knew about skis, although we have not yet discovered any, but finds from Russia show this possibility.”

And Burov responded: “We can assume that skis were known and used by the people of Ristola, Finland. The Heinola sled runners are similar to those at the Vis site. This similarity can prove that relations existed between Finland and northern European Russia, and that in Finland they used Vis and Veretje skis.”

The geography of the eastern Baltic offered good conditions for the invention of skiing. According to Polish archaeologist Zofia Sulgostowska, in the Preboreal (11,500 to 10,000 years ago), the Kunda and neighboring cultures lived on low plains dotted with ponds, lakes and gentle streams, offering in winter immense flat surfaces. The southeast Baltic was home to pine and birch forests. These conditions were very favorable to the systematic use of canoes in summer and sleds in winter.

runner unearthed at Vis. Burov.

From there skiing would have spread to similar terrain in neighboring Finland, Karelia and part of Lapland. Most of Finland is covered with lakes. Similarly, on the other side of the Urals, the land of the Khantys contains vast marshes, with many lakes and rivers.

Cultural conditions were also conducive to innovation. Archeology shows that the Mesolithics were particularly mobile, adventurous and inventive. The peculiar landscape of the eastern Baltic could only push them to develop new means of travel. The manufacturing sequence of the canoe, to the sled, to harnessing dogs, to skiing was easily within reach.

We can hypothesize on the date of the invention of skiing by first relying on the manufacturing process. We have seen that the skis and sled runner of Vis were carved from tree trunks, in the same way as dug-out canoes. Skis manufactured using this process were necessarily heavier and more fragile than skis made by bending planks. They certainly knew how to bend wood sticks with heat. We can suppose that they still used the carved-log process because the transition from sledge runner to ski was very new at this time.

The Start of Skiing in Siberia

East of the Urals, the oldest evidence we have are sled runners, which we know were in use by 7,000 years ago. Ski expeditions up the ice-covered waterways to Lake Baikal are plausible at that point. The Russian archaeologist G.M. Vasilevich concludes that the Tungus probably lived south of Lake Baikal in the Mesolithic, and it’s reasonable to conclude that Finno-Ugrians from the northwest brought skiing here first, along with their word suksi. As we’ve seen, the word suksi has been preserved in the Tungus-Manchu languages, specifically among the Evenki, who transmitted it to eastern Siberia.

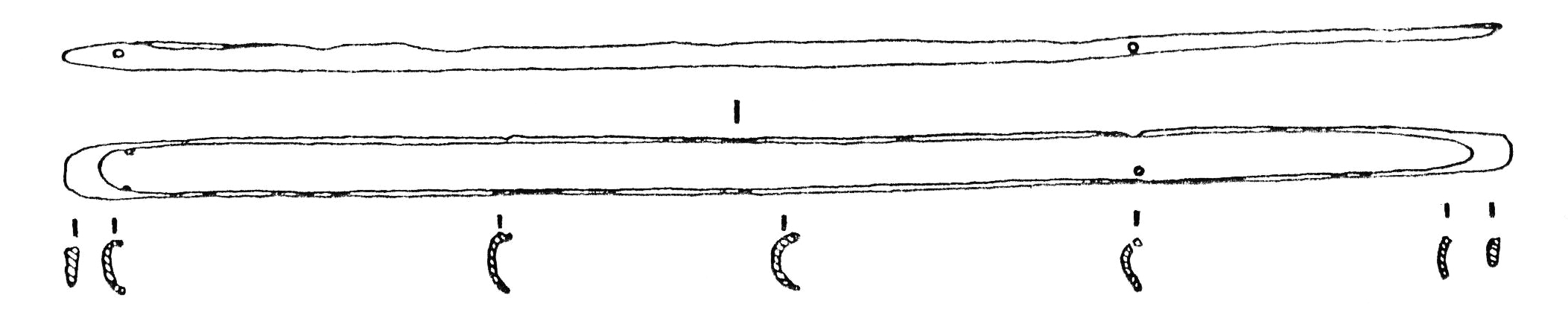

and 155mm wide, are about 5,200 years old. Toe

bindings laced through four holes drilled in the center. Åström and Norberg.

The oldest Siberian stone engravings of skiers are believed to be around 7,000 years old, but stone engravings cannot be carbon dated so their ages are notoriously difficult to estimate.

The four-hole ski-binding system tells us a little more. Skis with foot-plate and mortise, invented by the Saami in the Bronze Age, are carbon-dated to 3,400 years ago with the Høting (Sweden) ski. That design has never been found in Siberia, except in the Arctic trading post Mangazaya [founded 1600 AD].

After thousands of years of skiing in Siberia, one might expect to find more actual skis, or parts of skis. Apart from the unusual case of the Mangazaya skis, there are none. Not having been preserved in peat bogs as in Scandinavia, they have rotted or ended up as firewood.

This article is condensed from the final chapters of the ISHA Award-winning book Les Peuples du Ski: 10,000 ans d’histoire, by Maurice Woehrlé; Books on Demand, 2020. Engineer and skier Maurice Woehrlé ran Rossignol’s race-ski development for four decades, beginning with the Strato.

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

Warren and Laurie Miller

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corp.

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Berkshire East Mountain Resort/Catamount Mountain Resort

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sport Obermeyer

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sport

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboar Ski & Resort Corporation

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club