SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Ron LeMaster, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

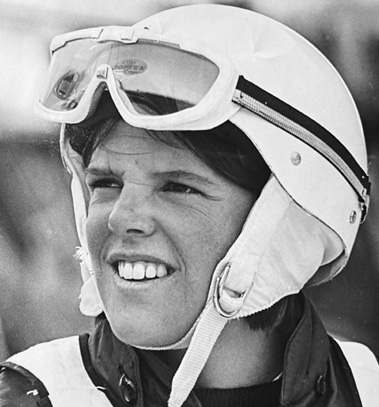

Kiki Cutter Densmore

Where are they now? The first American to win a World Cup race starts a new life.

Photo above: Kiki at the World Cup GS in Val d'Isere, December 11, 1969. Popperfoto/Getty Images.

Blasting out of her driveway onto River Road in Hanover, N.H., Kiki Cutter on her bike looks every bit the “Bend Fireball” that she was known as in her prime. Cutter is intent on prepping for her fifth knee surgery in as many years by riding up and down the Connecticut River from the home she shares with Jason Densmore, her friend for five decades, and husband of four years. Head down, focused, determined, this is the woman who, in 1968, became the first American, man or woman, to win on skiing’s World Cup Tour. Over a short three-year career, her five wins were a record until Phil Mahre surpassed it 11 years later.

where Kiki was the top US finisher.

Courtesy Kiki Cutter.

OFF TO THE RACES

Cutter grew up in Bend, Oregon, the fourth of Dr. Robert and Jane Cutter’s six children. She rode her horse to grade school from their 1,000-acre property, and in winters skied for the Bend Skyliners junior race program. Coach Frank Cammack, lumberman and national Nordic combined champ, taught his charges first and foremost to ski fast. “Every morning we would meet at the top of the mountain and we would scream down as fast as we could,” Cutter says. In those two to three runs before the mountain opened, Cutter fought all the boys to follow first behind Cammack. Among those young Skyliners, who as a group became a force in junior racing, was futuredownhiller Mike Lafferty. “I was at the lift first and she was second,” says Lafferty. “I don’t know if she ever beat me.” The two rode the lift together often and Lafferty remembers Cutter as “a great competitor who did everything full-tilt.”

Tough, kind-hearted and devoted, coach Cammack assumed an important role for Cutter when she was age 12 and her parents divorced. Cutter, already outspoken and independent, was now filled with anger. “She was an ornery brat under some circumstances and I didn’t hesitate to tell her that,” recalls Cammack. “When push came to shove she could really perform.” Cammack also appreciated the bigger picture, and what skiing could offer kids, especially young Kiki. “He saw what was happening with my family and directed my anger into skiing,” says Cutter. “He changed my life.”

At age 14, Cutter remembers sitting on the rocks at Mt. Bachelor, watching her U.S. Ski Team heroes—Heuga, Kidd, Barrows, Werner, Sabich—and wanting to be part of it. When she was invited to train with the team, at age 15, she caught the eye of Rossignol race room legend Gerard Rubaud, who gave Cutter her first pair of Rossi skis and started her lifelong relationship with the brand.

After winning the junior nationals downhill at age 17, in weather so severe it was said she “skied underneath the storm,” Cutter was named to the U.S. Ski Team, but not to the 1968 Olympic squad. Seven women were named to that squad in the spring of 1967. The following season, however, they had a few nagging injuries, and fewer good results. After Christmas, coach Bob Beattie brought three youngsters—Cutter, Judy Nagel and Erica Skinger—to Europe, hoping to spark some pre-Olympic fire in his team.

A WHIRLWIND TOUR

“Ferocious,” “tough,” “ornery,” “in-your-face” are all words teammate Karen (Budge) Eaton uses to describe Cutter’s loud entrance. “She made me laugh, and she fought back,” says Eaton, referring to Cutter’s liftline assertiveness, and how the rookie famously chided French superstar Marielle Goitschel to speed up or get out of the way on a training run. “She taught me how to be tougher and more aggressive,” adds Eaton. “We all got better.”

Despite their inexperience and poor start numbers, the youngsters immediately made a mark, and none more so than Cutter. She scored two seventh place finishes, then a second and third place, earning a spot, along with Nagel, on the Grenoble Olympic team.

Cutter was the only U.S. woman to ski all three events, placing as the top American in downhill, despite a bout with measles that the press never confirmed. Later that season, Cutter became the first American to win a World Cup race, taking the slalom at Kirkerudbakken, Norway. At the awards ceremony she was congratulated by King Olav V, and came home to a caravan welcome in Bend.

In an era when news stories referred to women as “girls,” called one champion skier “a hefty lass” and referred to the “good looks of the ski damsels,” the press loved the spirited Cutter. Dubbed by the French team “La Dangereuse Américaine,” she was simply “Kiki” in the local Oregon headlines. Elsewhere Cutter was described as a “105-pound fireball,” “fiercely tiny,” “pocket-sized,” “pixie-like” and “no bigger than a bar of soap.” Sports Illustrated asserted that Cutter “belies her ladylike cuteness with a fighting temperament,” and called her “the embodiment of the American skiing spirit.”

Much of this lives in scrapbooks kept by Cutter’s mother, Jane, who then lived in Geneva, Switzerland. Also preserved are letters from Kiki to Jane, recounting her travels, conveying how much she missed her, and defending her choice to interrupt her studies at the University of Oregon to commit to ski racing. Racing in Europe allowed Kiki and Jane to reunite, and provided a home base that was a respite for Kiki and her closest friend, Judy Nagel. Traveling by train with all their gear, as ski racers did then, was “a blast, that never felt like a job,” but was nonetheless exhausting.

Cutter notched three more victories in 1969, two slalom and one GS. She finished that season fourth in the overall World Cup standings, and second in slalom, while teammate Marilyn Cochran won the GS title. The following season, despite struggling with early season injuries, she managed to score her fifth World Cup win (and 12th podium) in St. Gervais, France, and many assumed her best years were ahead of her. But she had different ideas: “I was pretty burnt out and it wasn’t fun anymore,” she says. She quit in 1970, at age 20. Nagel quit the following year, with three victories, at age 19.

EARLY (AND BRIEF) RETIREMENT

Part of Cutter’s decision was the tense atmosphere on the U.S. Ski Team. Created by Beattie ten years earlier, the team was still establishing itself. Another major factor was that, to her mother’s displeasure, she had started dating Beattie, who in April 1969 had been ousted from the U.S. Ski Team. They married in July 1970.

At the 1972 Sapporo Olympics, which might have been Cutter’s Olympic moment, she attended as a spectator, while Beattie commentated for ABC-TV. She remembers Barbara Ann Cochran’s gold medal–winning performance: “I watched from afar and she made every turn perfect--so low down to the ground. I remember watching her and how proud I was of her.” Cutter says she was not a bit envious. “It was over for me.”

Cutter started racing on the pro tour, Beattie’s 1970 creation. She described the women’s competition as “a frill to the men’s race,” where the women were “stuck in after the men made their big ruts.” Cutter suffered her first serious injury in a collision off the six-foot-plus bump at Hunter Mountain.

Magazine event. Courtesy Kiki Cutter.

While Beattie was traveling, a group of kids from Aspen High School asked Cutter to coach them. She would later coach junior skiers at Sunlight, and tennis at Colorado Rocky Mountain School. Working with kids was rewarding—especially with the rebels. She could redirect their energy positively, as Cammack had done for her. “Those were periods of my life I absolutely loved,” she says.

Meanwhile, the marriage with Beattie, who was often on the road, was not going well. “What can I say about it? It happened,” Cutter offers. Their life in New York, where Beattie did much of his work, was especially chaotic. “I don’t think we ever had dinner alone together. I hated it.” They divorced after two and a half tumultuous years.

STARTING OVER

Cutter emerged with nothing but a condo in Snowmass (with two mortgages), and her name. She needed to make a living, doing whatever she could.

She soon teamed up with Mark McCormack of International Management Group, Jean Claude Killy’s agent and Beattie’s archrival. McCormack secured endorsements for Cutter with Nutrament, Ovaltine and Ray Ban, and was instrumental in getting her into the lucrative ABC Superstars competitions in 1975 and ’76. She excelled, thanks to months of intensive multi-sport training. In writing about that event for his 1976 book Sports in America, James Michener called Cutter “the best athlete pound for pound of the whole excursion, men or women.” When Martina Navratilova was heard to say “Who needs this?” of the grueling competition and training required to win the $30,000 purse, Cutter responded, “I do!”

Other endorsements she got on her own, including Busch CitySki, and citizen race clinics through the Equitable Life Family Ski Challenge. After her second knee injury racing on the Women’s Pro Ski Tour (started in 1978), Cutter reserved her competition for dominating the tamer celebrity events. She won the Legends of Skiing GS in 1987 and the initial Tournament of Champions series in 1990. Throughout, Cutter kept up her relationship with Rossignol, leading the women’s clinics they started. In 1994 she took on the role as Ritz-Carlton’s Ski Ambassador.

Cutter supplemented her promotional business by producing special inserts for SKI Magazine that doubled as on-site programs at World Cup events, and also hosted a monthly “Ask Kiki” column in SKI. She founded The Spirit of Skiing, a nationally televised fundraising event for People magazine, where the ski and celebrity world convened to raise money for ovarian and prostate cancer. Cutter was elected to the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame in 1993 and to the Colorado Ski Hall of Fame in 1998.

BACK TO BEND

After 30 years in Aspen, Cutter returned to Bend in 2000. There, she parlayed her publishing experience into her own magazine venture, Bend Living. The hefty quarterly averaged 160 glossy pages, filled with premium editorial, ads and photography, and became the top selling publication in central Oregon, winning awards for both design and editorial. It was a perfect fit for Bend, which was experiencing a spectacular real estate boom.

Managing the magazine and 14 employees was also an enormous amount of work, and all-consuming for Cutter, who took no time off. “It goes right back to why she was good at ski racing,” says Lafferty. “Her competitive nature is what carried her through.” In 2008 the financial crisis, and the collapse of the real estate market, hit publishing—and Bend—especially hard. As advertisers reneged on their agreements, and the magazine struggled for cash, Cutter scrambled to get loans and enforce contract payments. Eventually, however, the magazine folded, leaving her in substantial debt. “I had never experienced a loss like that,” says Cutter, who felt that she had failed her employees and her town. Once again, she faced rebuilding her life.

Kiki Cutter.

NEW LIFE AND AN OLD LOVE

It was just around then that Jason Densmore got in touch. The two knew each other from their days in Aspen, when Jason (former member of the U.S. Nordic Combined team) owned a woodstove store, The Burning Log. Then, each of them had been in other relationships, but they became friends and had stayed in touch. As her business was folding, so, too, was his marriage. While consoling each other they realized that rather than trying to resurrect a marriage and a business, they could instead try starting something new. They did, and it was a life together. Kiki moved across the country with Jason in 2010, to his home in Hanover, New Hampshire. The two have lived there ever since, marrying in 2017. After selling properties in Colorado and Oregon she is now debt free, and the couple has time to enjoy the outdoors with their shared menagerie of animals that match their demeanors. The terrier and cat are Kiki’s. The retriever is Jason’s.

Looking back on what she is proud of, there are the ski racing accomplishments, but what resonates more are the less celebrated products of her lifelong hard work, like the magazine and helping others, as when coaching rebellious teens. When asked what she is proudest of in her life, Kiki responds without hesitation: “Jason. I truly have been blessed, starting with Frank [Cammack] and then with Jason.” Whatever comes next, Cutter, now officially Densmore, will live by one of her friend Jimmie Heuga’s favorite mantras: “Keep on keepin’ on.”

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

Warren and Laurie Miller

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corp.

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Berkshire East Mountain Resort/Catamount Mountain Resort

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sport Obermeyer

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sport

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboar Ski & Resort Corporation

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club