SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

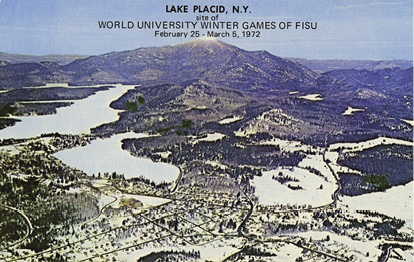

History of the World University Games

Dating back to 1928, the biennial Winter University Games will return to Lake Placid in 2023.

The 2021 World University Winter Games, scheduled for Lucerne, Switzerland, last December, were canceled due to pandemic-related travel restrictions. Lake Placid, New York, is set to host the next edition of the biennial winter games in January 2023.

The idea for the Games emerged from the 1891 Universal Peace Congress in Rome, which proposed a series of international student conferences that would include sports events. While the conferences never happened, the concept led Frenchman Jean Petitjean and modern Olympics founder Pierre de Coubertin to create the International Universities Championships, hosted by the Confédération Internationale des Étudiants (CIE). Summer games were held in Paris (1923), Prague (1925), Rome (1927), Paris (1928), Darmstadt (1930), Turin (1933), Budapest (1935), Paris (1937), and Monaco (1939), and then were halted by World War II. A number of “winter” events were actually summer games held in September.

In the autumn of 1924, Walter Amstutz, Willy Richardet and Hermann Gurtner held the first meeting of the Swiss Academic Ski Club (SAS), and over the next three years organized downhill and slalom races between Swiss and international university teams in Mürren, Wengen and St. Moritz. In 1928 these races culminated in the First International Academic Winter Games, in Cortina d’Ampezzo, Italy. Because the event was endorsed by the CIE, many consider the Cortina races to be the progenitor of the Winter Universiade. The 1928 downhill and slalom were organized by SAS president Gurtner; both races were won by André Roch. The Academic Winter Games were held five more times before World War II, from 1933 on in odd-numbered years to avoid conflict with the Winter Olympics and FIS World Championships.

The Games were restarted in 1947, but soon afterwards the CIE disbanded, and successors arose on either side of the Iron Curtain. Western countries formed the International University Sports Federation (FISU) in 1949, while Eastern European nations had their own Union Internationale des Étudiants (UIE). The two groups held their own rival summer and winter games until 1957, when Petitjean was able to hold a summer games in Paris, including Soviets and a token team of six Americans. Thus was revived the term Universiade, implying that students of all nations could compete.

The first post-war Winter Universiade was held in Chamonix in 1960. Charles de Gaulle opened the ceremonies, with 151 athletes from 16 countries participating in 13 events in five sports. Thereafter, games were held in Europe on a two-year schedule, and the Seventh Winter Universiade came to Lake Placid in 1972.

The small village in New York’s Adirondack Mountains had hosted the 1932 Winter Olympics. After World War II, facing vigorous wintersports growth in New England and Colorado, the resort town lost its luster. Locals saw international sporting events as a route to reinvigorating the economy, and in 1960 they launched a new Olympic Organizing Committee.

Rebuffed in its initial attempts to gain a second Olympic bid, the organizers looked for alternatives. By the late 1960s, it appeared that Denver would be the U.S. choice to host the next winter Olympics. The best alternative multi-sport international competition was the World University Winter Games. While some upgrades were necessary, Lake Placid had the competition and hospitality facilities in place. All the town needed was money.

National federations balked at the cost to fly teams across the Atlantic. With the backing of New York State, Lake Placid offered a package including round-trip airfare, busing from Montreal, lodging in Lake Placid, and breakfast and dinner daily. The total price for participants: $324 per person. The deal was done.

Opening ceremonies were held February 26, 1972. There would be 25 competitions in seven sports: Alpine and Nordic skiing, biathlon, ski jumping, figure skating, speed skating and hockey. There were 351 athletes from 23 countries. The games were just a few weeks after the close of the 1972 Winter Olympics. While there was some overlap, most participants had not competed in the Sapporo Games.

The start of the Universiade was not exactly what organizers had planned. The opening parade from the Lake Placid Club to the outdoor arena at the speed-skating oval got a late start, leaving spectators restless in the evening cold. “There was a lot of horseplay,” recalled Jim Rogers, local ceremonies chief. By the time the athletes entered the arena, discipline had given way to youthful exuberance. The Italian team commandeered a sleigh and circled the oval while singing songs. The torch bearer was American skier James Miller. As he ascended the podium, oil from the torch he was carrying spilled, and the sleeve of his wool sweater caught fire. He was able to slap down the flame and light the cauldron—but it was an inauspicious start to the ceremony. Richard Nixon was busy, concluding his historic trip to China and sent a brief message read from the podium. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller was a no-show. “The wonderful part of the opening ceremonies was the brevity of the speeches,” noted one local newspaper columnist.

The competitions went off as scheduled. Arrangements for athletes were praised. The major issue was weather: spring came early. Roby Politi, village native and two-time All-American skier, remembers temperatures going from “cold to warm to cold to warm, to even warmer.” Temperatures, below zero at the opening ceremonies, at one point reached 58 degrees Fahrenheit. “I remember ruts a foot deep on the course,” says Politi, who finished 20th in the giant slalom. It was worse for the Nordic skiers and speed skaters, who raced on slush.

Ski Team B squad, won Alpine

combined gold. The Stanford grad

went on to a career on stage and

screen.

U.S. athletes finished a distant second in the overall medal count with seven, behind 29 won by Soviet students. The best American skiing result was turned in by Stanford University’s Caryn West, who took the overall Alpine gold medal. Canadian Lisa Richardson won the women’s downhill by 3/100th of a second.

In his final report to the FISU organizers, Austrian official Prof. Werner Czisiek noted “the Winteruniversiade 1972 in Lake Placid must be called a great success.” He enthused about the logistics of transportation and efforts “to arrange different activities to bring people into contact with people of other nations.”

The successful 1972 Games proved to be a key factor a couple of years later, when Denver withdrew from hosting the 1976 Winter Olympics. Innsbruck stepped up as the replacement and Lake Placid, with facilities and organization in place, was selected for 1980.

And so Lake Placid will get the centennial Universiade to number 30 in the winter series (it would have been 31 had the Lucerne events taken place). More than 1,600 athletes, ages 17 to 25, from more than 50 countries and 600 universities are expected to compete in 86 medal events in 12 sports over 11 days. It will be only the second time the Winter Games have been held in the United States. (Buffalo, New York, hosted the summer version of these games in 1993.)

New York State, through its Olympic Regional Development Authority (ORDA), has invested more than $300 million to upgrade its winter sports venues. All facilities now meet international competition standards.

Phil Johnson is the longtime ski columnist for the Daily Gazette in Schenectady, New York.

SNAPSHOTS IN TIME (OLYMPIC EDITION)

1931 French Wine vs.Prohibition Paris—The French athlete’s wine is so important an item of his training diet that the government will be asked when Parliament meets next week to seek permission for the Olympic team going to Lake Placid, N.Y., to take wine along. Deputy Poittevin served notice today that he would ask the Premier to intercede with the American Government so that the skaters and skiers might have the “necessary rational ingredient of their training regime.” — “French Deputy Wants U.S. to Permit Wine to be Brought Here by Olympic Athletes” (New York Times, November 5, 1931)

1960 Pedal to the Metal During the 1959-60 season, the French ski manufacturer that supplied the national team had provided Jean Vuarnet with wooden skis that he found far too flexible. “It was a disaster,” Vuarnet said. “So I went to their factory in Voiron and had a good look around. I came across a pair of metal skis that were just my size. They’d been tossed aside but they looked okay to me. I took them and tried them out in the Émile Allais Cup in Megève. One of the skis got bent but I still managed to finish fifth. So I called the manufacturer and asked them to send me a new pair because the [1960] Games were coming up.” Vuarnet became the first skier in Olympic history to win gold on metal skis. — “Vuarnet Takes Downhill Skiing to the Next Level” (Olympics.Com, February 1960)

1972 Colorado Olympic DNF Denver—The Olympic torch will not be passed to the Rocky Mountains in 1976, top organizers of the Winter Games said Tuesday after voters in Colorado cut off state funds for the event. Clifford Buck, of Denver, president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, said, “Needless to say, it is a tremendous disappointment to me. I think it’s a tragedy for the state, and a tragedy for the nation that the people of Colorado were not aware of the great privilege and great honor to host the 1976 Winter Games. But the majority has spoken.” — “Voters Reject ‘Privilege’”(Eugene Register-Guard, November 8, 1972)

1992 Olympic Training, the Tomba Way At five o’clock, Tomba will get down to the serious business of training, but for the moment nothing is more important than enjoying the last days of summer lolling on the beach in the company of a lovely teenage girl whom he met while serving as a judge for the Miss Italy contest. — Patrick Lang, “The Road to Alberto-ville” (Skiing Magazine, January 1992.)

2006 Golden Aamodt Sestriere Borgata, Italy—Someone said if you looked at his media guide picture without knowing he was a skier, you’d think he were a bank president. Yet, Norway’s Kjetil Andre Aamodt made more Olympic history at Sestriere Borgata when, out of the 25th start—he zipped down in 1 minute, 30:65 seconds and made it stand up against Austria’s Hermann Maier, who finished .13 of a second back—he won the gold in the super-giant slalom. Aamodt came to Turin as the all-time alpine leader in medals with seven. Now he has eight. — Chris Dufresne, “Norway’s Aamodt shocks in super-G” (The Baltimore Sun, February 19, 2006)

2010 Peak Performance For the athletes, the Olympics, as he described them, were a festival of internationalism and frenzied liaising—“It’s a Small World” meets Plato’s Retreat. The impression I got was of an Athletes Village teeming with specimens of youth and fitness, avid men and women who’d spent their ripest years engaged in fierce, self-denying pursuit of peak physical performance, and who now, mostly after they’d competed, could throw off their regimens, inhibitions, and sweats, and pair off, with Olympic vigor and agility. It changed the way I watched the Games. And it made me wish I’d worked a little harder in practice. — Nick Paumgarten, “The Ski Gods” (The New Yorker, March 15, 2010)

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner of America

Boyne Mountain Resort

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club