SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

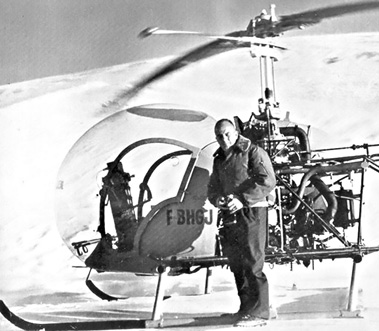

Prehistory of Heliskiing

Before Hans Gmoser and Mike Wiegele made it a success, heliskiing had unsung pioneers.

The helicopter has been called the God Machine for its ability to hover and land on almost any kind of terrain. One has even summited Mount Everest: On May 14, 2005, test pilot Didier Delsalle braved high winds to perch a Eurocopter AS350 B3 on the summit for 3 minutes, 50 seconds, repeating the landing the next day. No one has done it since.

Photo above: Hans Gmoser (right) with five guests and a pilot, with a Bell 47B1, at Valemount in 1969. Courtesy CMH.

In decent weather, helicopters can land anywhere on earth. That wasn’t always the case. An early Bell 47G2 with a 260-horsepower piston engine could barely hover and land at 10,000 feet (3,048 m) in still air. That was just high enough to reach the ridgelines, if not all the summits, in British Columbia’s Bugaboos.

Hans Gmoser, widely credited as the inventor of heliskiing, came to Canada from Austria in 1951, at age 19, and quickly became known as a top climber. He opened his own guide service in 1957, and in 1963 helped found the Canadian Mountain Guides Association. Gmoser himself said that the idea of heliskiing was first brought to him by Art Patterson, a Calgary geologist and a skier. Patterson had used helicopters in the mountains for summer fieldwork, and he knew that a lot of these machines were sitting idle during the winter months. He thought that hauling skiers could be an interesting new business. He also realized that to make the idea work, he would need professional guides who understood routefinding, snow and avalanches. Gmoser and Patterson teamed up, with Patterson handling the business side and Gmoser the guiding.

Their first heliski adventure began in late February 1963. Twenty clients, organized by Brooks and Ann Dodge, paid $20 each (approximately $160 in today’s dollars) for a day on Old Goat Glacier, 10 miles south of Canmore, Alberta. The result was disappointing. The two-seat Bell 47G2 helicopters could fly only one passenger at a time and climbed at less than 850 feet per minute; it took hours to get everyone to the 8,200-foot (2,500 m) summit. Then the snow conditions turned out to be less than ideal. They tried another heliski day in May, but encountered high winds that limited the possible landing zones. Patterson decided that heliskiing was a risky business and dropped out. But Gmoser saw the potential in helicopters.

He eventually renamed his guide service Canadian Mountain Holidays and, with the advent of fast-climbing, heavy-hauling, jet-powered helicopters, was able to create a successful heliski and helihike operation.

That’s the accepted version of heliskiing’s genesis. But earlier pioneers preceded Gmoser and Patterson.

1948

Writing in Vertical magazine (March 2012), Canadian aviation writer Bob Petite reported, “The first recorded occurrence of a helicopter being used to airlift skiers into mountains was back in 1948, by Skyways Services, which was one of three Canadian commercial operations at the time.” This wasn’t heliskiing proper—it was an air taxi service from Vancouver to the summit of Grouse Mountain ski resort (1,231 m, 4,039 ft). The fare-paying passengers then skied the lift network.

1950

In 1950, pioneering avalanche expert Monty Atwater used a helicopter while surveying Mineral King Valley, the proposed Disney ski resort in California. Elevations ranged from the valley floor at 7,400 feet (2,300 m) to surrounding peaks of more than 11,000 feet (3,400 m). In his book

Avalanche Hunters, Atwater wrote:

landed a specially-lightened Bell 47G on

the summit of Mont Blanc (15,777 feet,

1808 meters), carrying mountain guide

Andre Contamine.

“In Northern California I once did a job surveying a complex of ski areas of the future. My companion and I used a chopper first of all to jump over the snowbound (i.e., closed for the winter) highways. Then we used it as a ski lift with an infinite number of lines. It flew us to the top, picked us up at the bottom, flew us to a different top. In three days of about three hours of flying time apiece we did more work than we could have in a month on foot and with Sno-Cats, and we did it better. It was an aerial platform for making maps and photographs. If one of us got hurt, our angel of mercy was slurruping overhead. I have ridden helicopters from Chile to British Columbia, and I have great affection for them.”

Clearly, Atwater was heliskiing. His wife, Joan, did realize how much fun it could be. Atwater wrote: “As soon as she knew that there was a chopper on the program, Joan began propagandizing for a ride in it. ‘Not a chance,’ I told her. ‘Do you have any idea how much it costs per hour to fly this doodlebug? Besides, it’s a government job and the government doesn’t approve of using its equipment for joy riding.’”

Much later, in 1965, Disney also hired Swiss avalanche researcher (and Aspen skiing pioneer) André Roch to study Mineral King. Roch, too, used a helicopter to access the higher bowls, and he brought along other skiers on these trips. If Disney had known, he might have become the first heliski vacation developer. Regardless, Mineral King Ski area was never developed due to opposition by environmental groups.

1957–58

Bengt “Binx” Sandahl moved to Alta, Utah, in 1953 and worked as a bartender in the Alta Lodge. There, he became interested in snow and avalanche work, and, according to his daughter, he talked frequently with Atwater, who was by then director of the avalanche research center. The following year he left to take a job in Alaska, where he eventually worked as a ski instructor at Alyeska. Skiing magazine (February 2007) reported that in 1958, Sandahl guided skiers using a helicopter. Video exists of an Alouette II—the first turboshaft helicopter, introduced in 1956—carrying four skiers and a pilot at Alyeska, around that time. Sandahl apparently hauled skiers to Max’s Mountain on the south rim of Alyeska’s bowl, charging $10 per ride for up to 100 skiers per day. Sandahl later became Alyeska’s snow safety director. Returning to Alta, he was hired as the U.S. Forest Service snow ranger in 1964. He then used helicopters to drop explosives into avalanche chutes.

The January 1959 issue of SKI magazine ran an article entitled “By Helicopter to Virgin Snowfields,” about replacing ski-equipped planes with helicopters for glacier skiing in Alaska and the Alps. “By helicopter it is possible to ski unbroken powder all day long without ever seeing ski tracks except the ones you make yourself.” The reference to heliskiing in Alaska is to Sandahl’s operation. The article reported that at Gstaad and at Val d’Isère, skiers could ride for $22 to $52 per flight—about $176 to $416 today. Heliskiing has never been cheap.

1960s

In 1963 Bob Hosking was flying skiers from the Rustler Lodge at Alta. It’s not clear if he held a special use permit that allowed this. It’s said that for $5 or $10 one could buy a lift to Mount Superior, above Alta.

The big breakthrough, as Sandahl had found, came with jet engines. In 1961 Bell introduced the turboshaft-powered 204/205 series helicopters, capable of flying 10 to 14 passengers and climbing 1,750 feet per minute. That was more than 20 times the performance of a Bell 47.

for efficient heliski operations. That's Mike Wiegele

skiing. Courtesy MWH.

Before long, the 205 was outfitted with a 1,500-horsepower engine. So equipped, by the late 1960s, Gmoser really had CMH up and running. Sun Valley owner Bill Janss skied with Gmoser in the Purcell range and in 1966 launched Sun Valley Heliski. Mike Wiegele started his operation in Valemount, British Columbia, in 1970 and moved down the road to Blue River in 1974. In 1973 Wasatch Powderbird Guides started operations in Utah (Hosking was a partner). By November 1982, Powder magazine listed 15 heliskiing operations in the Lower 48 states alone.

Learning curve

The early leaders in heliskiing learned by trial and error. Protocols were needed for both helicopter and avalanche safety. Once the boom started, Gmoser and Wiegele, in particular, faced a shortage of qualified guides, the reason for the foundation of the Canadian Ski Guides Association (CSGA) in 1990. CSGA now has about 130 members, and heliskiing contributes more than $160 million annually to the economy of British Columbia.

Fat skis: A second boom

By the late 1980s, the rising cost of aviation fuel was cutting into profits for heliski operators. The crunch was exacerbated by a limited pool of capable powder skiers—there simply weren’t a lot of skiers who could handle bottomless powder on the 68 millimeter–waisted straight skis of the era. Then in 1988, one of the competitors in Mike Wiegele’s Powder 8 contest contacted Rupert Huber at the Atomic ski factory and asked for a fatter powder ski. Huber responded in 1990 with the Powder Plus fat ski (112 mm waist width). Wiegele adopted and promoted the concept. Fat skis took off, and heliskiing resumed growing.

First Heavy Lifter

helicopter. EADS-Messerschmitt

Foundation.

Use of helicopters in mountainous terrain depends critically on engine power. The first machine to lift significant loads at higher elevations was the German Focke-Achgelis Fa-223 Drache (Dragon), a twin-rotor design that first flew in 1940, powered by a 1,000-horsepower radial engine. Climb rate was 1,700 feet per minute. Theoretical service ceiling was 23,000 feet (7,100 m) at light weight, and 8,000 feet (2,440 m) with a full payload of 1,000 kg (2,200 lb). This was better than twice the performance of the much smaller Bell 47.

A Fa-233 is known to have crashed on Mont Blanc in 1944 during an attempted mountain rescue. Mountain flight testing resumed in Mittenwald in the Bavarian Alps in September 1944, with an emphasis on hauling heavy cargo to mountain troops—howitzers, for instance. The highest landing was at 2,300 meters (7,549 ft) while testing performance as an air ambulance. By then the factory had been repeatedly destroyed by Allied bombers and the project was abandoned. Of 11 built,only three survivedthe war. Neither of the Austrian-born pioneers of Canadian heliskiing, Hans Gmoser and Mike Wiegele, were aware of the German experiments.

Halsted Morris is president of the American Avalanche Association. His patrol handle is “Hacksaw.” See his website at heliskihistory.com.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Bogner of America

Boyne Mountain Resort

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club