SKIING HISTORY

Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Seth Masia

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Chan Morgan, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Chan Morgan, Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, Chris Diamond, David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Rick Moulton, Wilbur Rice, Charles Sanders, Bob Soden (Canada)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Business & Events Manager

Kathe Dillmann

P.O. Box 1064

Manchester Center VT 05255

(802) 362-1667

kathe@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

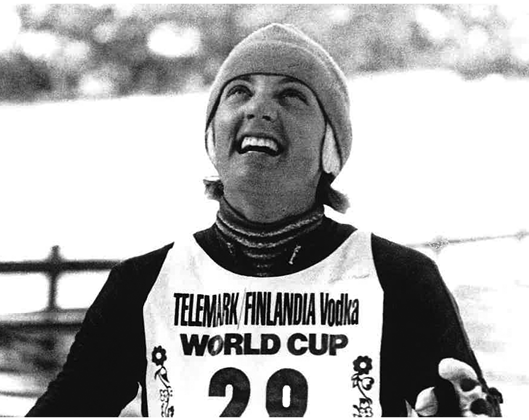

Alison Owen Bradley

The first American to win a World Cup cross-country race, this pioneer has remained an advocate for women for five decades.

Photo above: Alison at the U.S. Nationals in 1977. Courtesy Alison Owen Bradley.

Trivia question: Who is the first U.S. racer to win a FIS cross-country World Cup?

Division, Alison bashed the gender

barrier at age 13, at the 1966 Junior

Nationals, Winter Park. AOB.

Kikkan Randall, or maybe Jessie Diggins? Nope. The answer is Alison Bradley (née Owen), who won the first-ever women’s FIS World Cup in December 1978. A member of the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame Class of 2020—to be officially inducted at some point in a post-pandemic world—Bradley is only the second female cross-country skier to be inducted into the Hall of Fame (her former teammate Martha Rockwell was in the HOF Class of 1986).

relation) at the 1968 Winter Park training

camp. AOB.

“Having spent so much of my life devoted to excellence in the sport of cross-country skiing, and then to be recognized and honored for it by the Hall of Fame, is icing on the cake!” Bradley said by phone from her winter home in Bozeman, Montana. She lives with her husband, Phil Bradley, on a small hobby farm near Boise, Idaho, during the summer months.

It’s been a long time coming for Bradley, a pioneer of women’s cross-country skiing in the United States. Since retiring from competition in 1981, Bradley has coached and promoted women’s cross-country skiing. Most recently, Bradley, Randall, and 1984 Olympian Sue Wemyss started U.S. NOW—U.S. Nordic Olympic Women—a group of all the American women who have competed in cross-country skiing at an Olympic Winter Games.

“There are 53 of us, and we’re all still alive,” Bradley, 68, said. “How can we pass on what we learned to upcoming skiers?”

As a way to support current skiers, U.S. NOW has a “grit and grace” award.

First called the Inga Award—named after the unheralded mother of Crown Prince Haakon Haakonsson who was carried to safety by Norwegian Birkebeiners in 1206—Bradley presented it to Rosie Brennan at U.S. NOW’s first reunion in 2019.

“You always see the two Viking guys carrying the prince,” said Bradley, explaining the birth of the award. “You never hear about the boy’s mother. That’s kind of like women’s skiing. It really spoke to me that she would be a good example for us to persevere and be strong.”

Bradley’s aim is that U.S. NOW continues to inspire upcoming generations of female cross-country skiers. “We have a lot of passion for skiing and ski racing, but there hasn’t been a real big way to put ourselves back in,” she said. “Now we have a structure to work within.”

at the 1972 Sapporo Olympics. AOB.

The Early Days

Bradley had no female role models when she began cross-country skiing in the mid-1960s. Born in Kalispell, Montana, and raised in Wenatchee, Washington, Bradley was the second of five children in the Owen family, and like her father, she loved the outdoors.

One day, her father saw an ad in the Wenatchee World newspaper for a cross-country ski club. Herb Thomas, a Middlebury graduate and biathlete, had moved back to Wenatchee to work in his family’s apple business and wanted to teach area youth how to cross-country ski. Bradley, the only girl on the team, loved it. The next year, she beat several boys and qualified for a meet in Minnesota. But she was not allowed to compete.

“I couldn’t go because I was a girl,” she recalled, recounting an era in which female athletes were often ridiculed for competing, which was considered unattractive and even dangerous. “I was devastated.”

The next year, when she was 13, Bradley was one of nine Pacific Northwest Division skiers to qualify for the 1966 junior nationals in Winter Park, Colorado. This time, they let her go. But once she arrived, officials were not sure what to do with her. They finally allowed her to compete, but an ambulance was ready in case she succumbed to the effort (she didn’t).

World Cup XC race, eight-time U.S.

champion flashes a victory smiile. AOB.

Bradley does not remember the hoopla (she made laps on alpine skis at Winter Park while the race jury was deciding her fate), nor much about the race itself. For a 13-year-old, it was “just fun to be out of school and to have made the team.”

But Bradley had opened officials’ eyes. The following year, 17 girls qualified to compete at junior nationals, and they had their own race. By 1969, 40 girls participated in junior nationals, and the first senior national cross-country championships for women were held that year. Bradley had shattered her first glass ceiling.

‘First’ World Championships and Olympics

In 1970, the U.S. Ski Team sent its first women’s team to a FIS Nordic World Championship. A junior in high school, Bradley qualified for the team and left school for several weeks to travel behind the Iron Curtain to Czechoslovakia. Again, she remembers little from the 5k race, just that she was wide-eyed at the sights, so different than rural Washington.

American women made their Olympic debut in cross-country skiing at the 1972 Sapporo Winter Games. Galina Kulakova, a 29-year-old Soviet skier, swept the 5k and 10k individual races and anchored the Soviets to the relay gold medal—finishing more than five minutes ahead of the Americans, who crossed the line in last place. Bradley had just graduated from high school the previous spring and finished far back in both races.

Bradley asked U.S. women’s coach Marty Hall if she could just go home and taste success at junior nationals. “He would say, ‘Do you want to be a big fish in a little pond, or do you want to be a little fish in a big pond?’ I was getting eaten by the bigger fish, but it did wake me up to what I was working towards.”

Hall gave Bradley a training journal with Kulakova’s picture on the cover. “Someday you’re going to be right there with her,” he assured her.

But after 1974 world championships, Bradley had had enough. She was only 21 but felt as if her progress had stalled. She earned a scholarship to Alaska Methodist University (now Alaska Pacific University) and moved to Anchorage. She continued to compete domestically. But she was done with racing in Europe.

Then in 1978, the national championships were held in Anchorage. After winning the 7.5k and 20k races and finishing second in the 10k, Bradley found herself on another world championship team. “I’m not going back into that, I’m going to get my education,” she firmly told Jim Mahaffey, AMU’s ski coach.

Mahaffey persuaded her to try international competition again. She was good, he assured her. “Kochie had won an [Olympic] medal, ‘You know, maybe Americans can do well in this sport,’” she recalled thinking.

Physically and mentally more mature, Bradley was finally skiing near the front. In Europe, she finished top 10 in four races, including seventh at Holmekollen. It was like catching a touchdown pass in the Super Bowl.

In December 1978, Bradley made her mark. She had a good feeling at the Gitchi Gami Games in Telemark, Wisconsin—considered as the first FIS Cross-Country World Cup won by an American woman or man, though the FIS classifies it as a “test” event. “I knew in my heart I could win it,” she said. She just had to convince her body to go through the pain of racing. At that moment, Marty Hall walked into the lodge where Bradley was sitting. Hall was no longer the U.S. coach, but he looked across the room and pointed at Bradley. She looked back and thought, “Yes! I’m ready.”

Bradley won the women’s 5k that day and the 10k as well. With a handful of other top 10 finishes that season, she finished the World Cup ranked seventh overall. It was the best result by a U.S. woman until Kikkan Randall finished fifth overall 33 years later, in 2012.

The 1980 Olympic year was the best yet for Bradley. She won the Gitchi Gami Games again and finished on the podium in several World Cup races. In all, she made $35,000 in prize money—unheard of riches in a relatively unknown sport in the United States at that time. But at the 1980 Olympics in Lake Placid, she fell ill and finished 22nd in both races (5k and 10).

A year later, she won the last of her 10 national titles, then retired. “I was so discouraged by how up and down results would be,” she explained. “I could be right in there for some races, then people I had beaten were beating me at the big events. We wondered why our coaches couldn’t get us to peak.” She now recognizes the impact of performance enhancing drugs (PEDs) on the sport. In 1979, five of the six women ahead of Bradley in the World Cup rankings were Soviets and are strongly suspected of PED use.

“In hindsight, I give myself a lot more credit,” she said. “The doping scenario was confusing for racers like us because we had this attitude that we weren’t that good. But we friggin’ were that good!”

After Racing

Bradley moved to McCall, Idaho, after she retired and started a family. Her son, Jess Kiesel, helped the University of Utah ski team win an NCAA title as a freshman in 2003. Daughter Kaelin Kiesel was a two-time All-American and student athlete of the year at Montana State University (class of 2011).

After moving to Sun Valley in the mid-1980s, Bradley coached both Jess and Kaelin with the Sun Valley Ski Education Foundation, where for 14 years she helped several young skiers reach the world junior championships. Coaching at the world juniors, she once again confronted dominating males who weren’t good listeners. She knew more than most about training, ski prep, technique and, unlike her peers, had an impressive World Cup record. But she liked to concentrate on the mental approach to competition, and all the complex factors that lead to speed. “My style was very much about the person,” she said.

Then in the late 1990s, she saw a need for a program to help collegiate women make the national team. She founded WIND—Women In Nordic Development. Several WIND skiers competed in the world championships and made Olympic teams. But balancing the burden of fundraising, coaching, and raising her own kids, Bradley could not keep the WIND blowing for long.

In the mid-2010s, Sadie Maubet Bjornsen called Bradley out of the blue. The U.S. women’s team, led by coach Matt Whitcomb, wanted to learn more about the pioneering skiers who had laid tracks for the current women’s program. “I was in tears when Sadie emailed me,” said Bradley. “Really?! Someone remembers me?”

Bradley, Randall, and Wemyss ran with the idea, founding U.S. NOW. When Rosie Brennan received US NOW’s first award—and $1,000 to go with it—she was shocked. “I’ve had a lot of challenges in my whole career,” said Brennan, who was dropped for the second time from the U.S. Ski Team after she contracted mononucleosis during the 2018 Olympic year. “To be awarded this award from this group of people who have also gone through their own challenges means more than any race could ever mean to me.”

Two years after Randall and Jessie Diggins won America’s first Olympic gold medal in cross-country skiing (Team Sprint) at the 2018 PyeongChang Olympic Winter Games, Bradley was nominated to the U.S. Ski & Snowboard Hall of Fame, and several women on the 2018 U.S. Olympic team, plus Coach Whitcomb, penned a letter in support of her nomination.

“We are thankful for all Alison has done to further our sport, which gave us all something to dream about as young women,” read the letter. “The gold medal this winter has not only been an achievement for our team, but for the larger ‘team’ that Alison truly championed… all of (this) started with a leader who wouldn’t take ‘no’ as an answer.”

The hurdles Bradley-Owens and her colleagues faced in a male-dominated sport—and world—are in sharper focus now, but she’s pragmatic about the quest: Don’t blame the men, who deserve credit for organizing all the sports in the first place, she says, but step up yourself instead. “It’s been a slow change, but it is changing,” she says.

Peggy Shinn is a senior contributor to TeamUSA.org, has covered five Winter Olympic Games and is a regular contributor to

Skiing History.

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

BEWI Productions

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

Outdoor Retailer

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

Sport Obermeyer

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

Warren and Laurie Miller

World Cup Supply, Inc.

GOLD ($700)

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

NILS, Inc.

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour