SKIING HISTORY

Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Seth Masia

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

John Fry (1930-2020), Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Chan Morgan, Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Christin Cooper, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, Chris Diamond, David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Rick Moulton, Wilbur Rice, Charles Sanders, Bob Soden (Canada)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Business & Events Manager

Kathe Dillmann

P.O. Box 1064

Manchester Center VT 05255

(802) 362-1667

kathe@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Alpine Revolution: Three years that transformed skiing

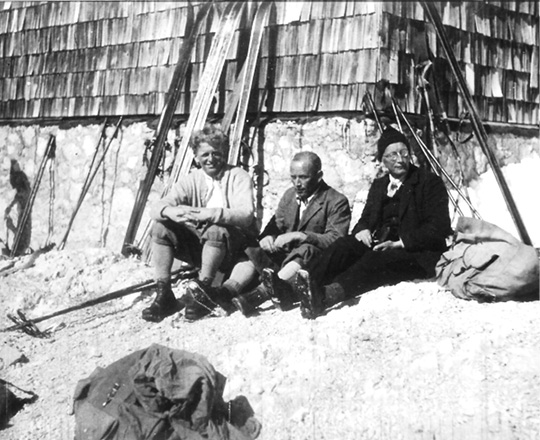

Photo above: Walter Amstutz led the transition from free-heel to locked-heel skiing. In 1928, he pioneered a spring to control heel-lift, soon known as the “Amstutz spring.” Reduced heel-lift helped spark the parallel turn revolution. Photo courtesy Ivan Wagner, Swiss Academic Ski Club

From 1929 to 1932, steel edges and locked-down heels transformed downhill and slalom racing into the high-speed alpine sports we love today.

It’s often said that alpine skiing was born in 1892, when Matthias Zdarsky experimented with skis adapted for steeper terrain, or perhaps with Christof Iselin’s 1893 ascent, with Jacques Jenny, of the Schilt in Switzerland.

But Zdarsky, Iselin and their heirs—including Hannes Schneider—were free-heel skiers and today we would lump them in with the nordic crowd. The sport we recognize as alpine skiing began with a pair of inventions that transformed downhill and slalom racing over the course of three winters, from 1929 to 1932.

Racers in Austria and Switzerland were primed for alpine competition, but lacked the tools for downhill speed. Kitzbühel held its first Hahnenkamm downhill in April 1906, won by Sebastian Monitzer at an average speed of 14 mph. Arnold Lunn launched the Kandahar Cup at Crans-Montana in 1911. After the Great War, Lunn headquartered at Mürren and in January 1924 founded the Kandahar Ski Club. This prompted Walter Amstutz and a few friends to launch the Swiss Academic Ski Club (SAS) the following month. Lunn intended the Kandahar to promote racing amongst his British guests—a rowdy assortment of public school Old Boys. Another contingent of sporting toffs infested the neighboring town of Wengen. Rivalry between the groups led the Wengen chaps, in 1925, to create their own ski-racing club. Because a railway ran partway up the Lauberhorn, the Wengen skiers disdained climbing. They called themselves the Downhill Only Ski Club (DHO).

Head of the Wengen ski school, Rubi won the

first Lauberhorn downhill. Photo courtesy

Pierre Schneider, Swiss Ski Museum

Downhill and slalom racing were still fringe sports, pursued by a few dozen people at half a dozen meets each year. Lunn often said it was just good fun, and no one took it seriously. The equipment—hickory or ash skis without edges, and bindings with leather straps—worked well only in soft snow. Downhills were gateless route-finding exercises. Winning time on a typical two-mile downhill might be 15 or 20 minutes, for an average speed around 15 mph. Low speeds meant that falls, while common, rarely produced serious injury. Racers expected to fall, get back up, and finish. Slaloms were usually set to produce a one-minute winning time, but every gate required an exaggerated stem turn. A smooth stem christie was the mark of an expert skier.

On hard snow, edgeless hickory skis slipped and skidded uncontrollably. Skiers dreaded any traverse across an icy or crusted steilhang. In 1931 Christian Rubi, director of the Wengen ski school and a founder of the Lauberhorn race, recalled the terror of wooden edges:

“Touring skiers are on a Whitsun tour in the high mountains. They take their skis to the summit, and prepare to descend. Then comes the traverse on the hard firn, above the bergschrund. One of them slips, his edges don’t grip, he falls, slides, tries to stop in vain, slips headfirst and disappears into the coal-black night of the yawning crevasse – After half an hour, rescue is at hand. Someone dives into the cold depths on a double rope. There the victim dangles head-down from his ski bindings, face bloody. . .”

at Matrashaus on the Hochkönig, south of

Salzburg. Note the Lettner edges on the

skis. Rudolf Lettner Archive.

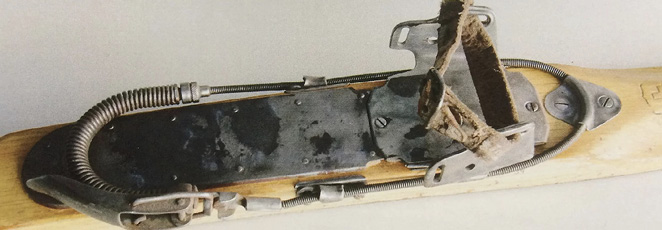

In December 1917, the mountaineer and ski jumper Rudolf Lettner had just such a scare during a solo tour on the Tennenbirge south of Salzburg. Lettner was able to self-arrest, stopping a potentially fatal slide by using the steel tip of his bamboo pole. Back at his accounting job, Lettner began doodling designs for steel edges. It took nearly a decade to figure out how to armor the skis without making them too stiff, but he filed a patent in 1926 for what we now call the segmented edge: short strips of carbon steel screwed to the edge of the ski-sole in a mortised channel.

Using steel edges, Lettner’s daughter Kathe finished second in downhill at the very first Austrian championships in 1928 (she reached the podium four more times in the next six years). Another early adopter was the 18-year-old ski instructor Toni Seelos of Seefeld, who used Lettner edges when he won a 1929 slalom at Seegrube—by five seconds.

Skiers outside of Austria heard about metal edges, but were skeptical. In 1927, Tom Fox of the DHO acquired a set of Lettners, but other Brits scoffed. Segmented edges looked fragile. Besides, 120 screws might weaken the ski. Arnold Lunn, after grumbling that some Englishman had tried unsatisfactory steel edges in the early ’20s, ran articles in the British Ski Yearbook suggesting that they made skis heavy, dragged in the snow, and inhibited turning. Beginners, he wrote, should by no means use metal edges. Over the next decade, experiments were made with continuous edges of brass and aluminum (continuous edges of steel proved far too stiff).

However, Lettner’s neighbors took notice. A handful of racers from the Innsbruck ski club saw an opportunity and on January 10-12, 1930, at Davos, they beat the pants off everyone at the second World Inter-University Winter Games. On Lettner edges, the Innsbruck boys took four of the top five places in slalom (and eight of the top 15 spots), plus the top four places in downhill. Notable were the Lantschner brothers, Gustav (Guzzi), Otto and Helmuth, who took first, second and fourth in downhill; Otto won the slalom with Helmuth fifth. On January 15, three days after the Davos triumph, Guzzi and Otto each went 65.5mph at the first Flying Kilometer, organized by Walter Amstutz at St. Moritz. They did it on jumping skis without steel edges, though they obviously hit the wax.

The Lantschners were hot but they had not previously been world-beaters. Only a year earlier, Guzzi came fourth in the 1929 Arlberg-Kandahar downhill and Otto tenth in the slalom.

It was obvious after the January 1930 races that steel edges were now essential for winning. Top “runners” scrambled for Lettner edges. The wealthy Brits of the Kandahar and DHO clubs were happy to pay a carpenter about $100 (in today’s money) to mortise their skis and sink about 120 screws.

downhill, tied for the slalom win at the first

Lauberhorn, on steel edges. Within weeks

all the top racers converted to the new

technology.

Verein Internationale Lauberhornrennen

In Wengen, Christian Rubi and Ernst Gertsch were convinced. Seeking to prove that local Swiss skiers could beat the Brits, they were busy organizing the first-ever running of the Lauberhorn, set for February 2-3. But Gertsch found time to take over the workbench at his father’s ski shop and install the new edges.

So equipped, they were able to beat the Lantschners. Rubi won the downhill, with three Brits following: Col. L.F.W. Jackson, then Bill Bracken, founder of the Mürren ski school, with Tom Fox third. Guzzi Lantschner settled for fifth, with Gertsch seventh.

The next day, Gertsch tied for the slalom win with Bracken. The next three places belonged to Innsbruck skiers, including Guzzi Lantschner in fourth, followed by Fox and Rubi. Bracken, who had grown up skiing in St. Anton, thus became the first Lauberhorn combined champion.

Over the space of three weeks, all the top alpine racers in Europe had converted to steel edges.

of the Murren ski school, was the first

Lauberhorn combined champ, on

Lettner edges. He was the only Brit

ever to win the trophy. Robert Capa

and Cornell Capa Archive, Gift of

Cornell and Edith Capa, 2010

In the Illustrated Sportsman and Dramatic News (London), Arnold Lunn wrote “The Austrian team at the Winter University Games last year had all provided themselves with steel-edged skis, and they scored a run-away victory in the slalom. Again, steel edges had a great triumph in the race for the Lauberhorn Cup which was held at Wengen in the middle of February. The snow in the Devil’s Gap was the nearest thing to genuine ice that I have seen on the lower hills in winter since I was nearly killed twenty-five years ago on a cow-mountain above Adelboden. The contrast between the ease and security of the racers with steel edges and the slithering helplessness of the other competitors was most impressive.” Lunn predicted universal adoption of metal edges and recommended armor for the lower legs to prevent lacerations.

Scotsman David A.G. Pearson of the DHO reported to Ski Notes and Queries (London), “At my particular sports shop in Wengen the first supply [of edges] was sold out almost immediately, and I had to wait some days before a new stock came in. I believe that our friends at Mürren were as keen as we were.” Pearson warned that “A certain amount of skill is needed for their use. . . . If, in doing a Christiania one gets for a fraction of time on to the outside edge of the lower ski, one can hardly avoid going over like a shot rabbit . . .” This may be the first reference in print to catching an edge.

In late February, after years of lobbying, Lunn finally persuaded the FIS to sanction alpine races (some accounts say that Walter Amstutz did most of the talking on Lunn’s behalf).

Swiss Ski Museum

Meanwhile, a parallel revolution was brewing. The switch from free-heel to locked-heel skiing began when Walter Amstutz took a close look at his bindings. Amstutz, like nearly every ski racer of his era, used a steel toe iron (Eriksen and Attenhofer Alpina were the popular brands) with leather straps over the toe and around the heel. Rotational control, not to mention what we would today call leverage control, was imprecise at best. In 1928, Amstutz introduced a steel coil spring to control heel-lift. The spring attached at one end to a leather strap above the ankle, and at the other end via a detachable clip to the top of the ski, about six inches behind the boot heel.

Arnold Lunn considered this a brilliant innovation. Beginning in 1929 nearly all top racers adopted the spring or some variant—less expensive competing versions used rubber straps. Decades later, Dick Durrance told Skiing Magazine’s Doug Pfeiffer, “The Amstutz springs were great. They held your boot to the ski. . . . we did add some strips of innertube for better tension.” By tension, Durrance meant heel hold-down.

Better control of the boot heel optimized the advantage of steel edges. Toni Seelos figured out how to cinch down his leather binding-straps to hold his heel solidly to the ski-top. He practiced jumping his ski tails around close-set slalom gates, using plenty of vorlage (forward lean) to get the tails off the snow so he could swing them sideways, in parallel, and land going in the new direction. The technique eliminated the draggy stem. Gradually he refined the movement, moving the tails sideways as a unit, without a visible hop.

course preparation was a thing, and fences

were no big deal. His friends called him a

“jumping devil.” Swiss Ski Museum

Amstutz’ friend Guido Reuge, a mechanical engineering graduate of ETH Zurich, went one better. With his brother Henri, in 1928 he cobbled up a new binding, the first to use a steel cable to replace leather straps. The cable tightened around the boot heel with a Bildstein lever across the back of the boot (the lever was later moved out ahead of the toe iron, where a skier could reach it easily for binding entry and exit). But the real innovation was a set of clips

Swiss Ski Museum

screwed to the sidewalls ahead of the boot heel. With the cable routed under the clips, the boot heel was clamped to the top of the ski for downhill skiing—English speakers called this effect “pull-down.” With the cable routed above the clips, you had a free-heel binding for climbing, touring and telemark. Reuge called this the Kandahar binding. He received a patent and began selling it in 1932. The two new technologies—steel edges and locked-heels—worked perfectly in concert, enabling all forms of stemless turning.

Meanwhile, Seelos perfected his skidless parallel turn. The concept was new and unique: No practitioner of Arlberg had ever thought of it. As late as 1933, Charley Proctor wrote in The Art of Skiing that the ultimate downhill turn was the “pure Christiana,” which skidded both skis.

That year Seelos brought his new turn to the FIS World Championships and won the two-run slalom by nine seconds over stem-turning Guzzi Lantschner. (For the full story of the Seelos turn, see “Anton Seelos” by John Fry, in the January-February 2013 issue of Skiing Heritage.) Seelos instantly transformed from ski instructor to international coach, and over the next two decades taught parallel turns to Olympic and world champions from Christl Cranz and Franz Pfnur to Toni Matt, Emile Allais and Andrea Mead Lawrence.

Decades later Durrance told John Jerome: “Seelos . . . developed this knack for getting through slalom gates like an eel. In the first FIS that he ran I think he won the slalom by something like thirteen seconds. He was head and shoulders above anybody else. He was my idol when I left Germany [in 1933]. . . With nothing but your weight shift you cut a carved turn, letting the camber of the ski do the turning for you.”

1939, equipped with Kandahar bindings

and Amstutz springs reinforced with inner

tubes. Ellis Chapin

“I thought I’d just start skiing slalom like Seelos and I’d beat anybody,” Durrance said. If “anybody” meant any North American, he was right. But he couldn’t beat another Seelos fan, the professional Hannes Schroll, winner of the 1934 Marmolada downhill and new ski school director at Yosemite.

Like the steel edge, the Kandahar binding became an instant must-have for alpine racing, and then for all alpine skiers. The binding was manufactured under license, or simply copied, by numerous companies around the world. Under a variety of brand names (for instance, Salomon Lift) it remained the standard alpine heel binding design into the 1960s, long after the Eriksen-style toe iron was replaced by lateral-release toes. Some of the top racers, including Durrance, used both the Kandahar and the Amstutz spring for extra pull-down.

With new technology, race times tumbled. In 1929 at Dartmouth’s Moosilauke downhill, Charley Proctor set the fast time of 11 minutes, 59 seconds on the 2.6-mile course (average speed 13mph). He had hickory edges and free-heel bindings. By 1933, with steel edges and Kandahar bindings, he had it down to 7:22 for an average 20.25mph.

In 1930 the Lauberhorn start moved up to the summit, and assumed its modern length of 4.4km (2.7 miles). Christian Rubi won that race in 4:30.00, for an average speed with steel edges of 36 mph. In 1932, with heels locked, Fritz Steuri knocked 20 seconds off that time for an average speed of 38.9 mph.

Top speeds were getting interesting, and alpine racing became a spectator sport. At the 1936 Olympics in Garmisch, 50,000 people turned out to watch the slalom. The winner was Franz Pfnur. But there was a faster skier on the course. Toni Seelos, ineligible to race because he was a professional instructor and coach, was the forerunner. He beat Pfnur by five

seconds.

Pretty soon skiers didn’t even have to unlock their heels to reach the race start. A few resort hotels had already built rack railways and Switzerland’s first cable-pulled rail car, or funi, opened in 1924 at Crans, the first cable tram in Engleberg in 1927, Kitzbühel’s Hahnenkammbahn in 1928, and Ernst Constam’s T-bar at Davos in 1934. The race was on for uphill transportation, and alpine skiing had conquered Europe.

Sources for this article include numerous reports in Der Schneehase and in the British, Canadian and American Ski Year Books for the years 1928 through 1939. Thanks to Einar Sunde for scanning many of these articles from his own library. Dick Durrance quotes from The Man on the Medal by John Jerome and from Skiing Magazine. More details from Snow, Sun and Stars, edited by Michael Lutscher.

Other photo credits for the print edition: Guzzi Lantschner photo from Getty Images; Toni Seelos photo source unknown.

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

BEWI Productions

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

National Ski Areas Association (NSAA)

Outdoor Retailer

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

Sport Obermeyer

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

Warren and Laurie Miller

World Cup Supply, Inc.

GOLD ($700)

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

NILS, Inc.

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour