SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Wendolyn Holland, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Einar Sunde, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine, Lindsey Vonn

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Jamie Coleman

(802) 375-1105

jamie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Boot Camp on Mount Rainier

A week after Pearl Harbor, John Woodward and Paul Lafferty began teaching Army recruits to ski on Mount Rainier.

By John W. Lundin

In these pages, and in at least 40 books, the story has been told of how Charles Minot “Minnie” Dole and John E.P. Morgan, of the National Ski Patrol, lobbied the U.S. Army to establish a winter and mountain warfare unit, the 10th Mountain Division, beginning in June 1940.

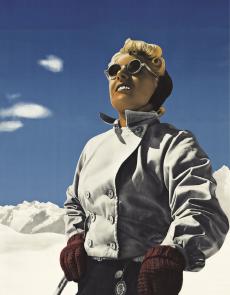

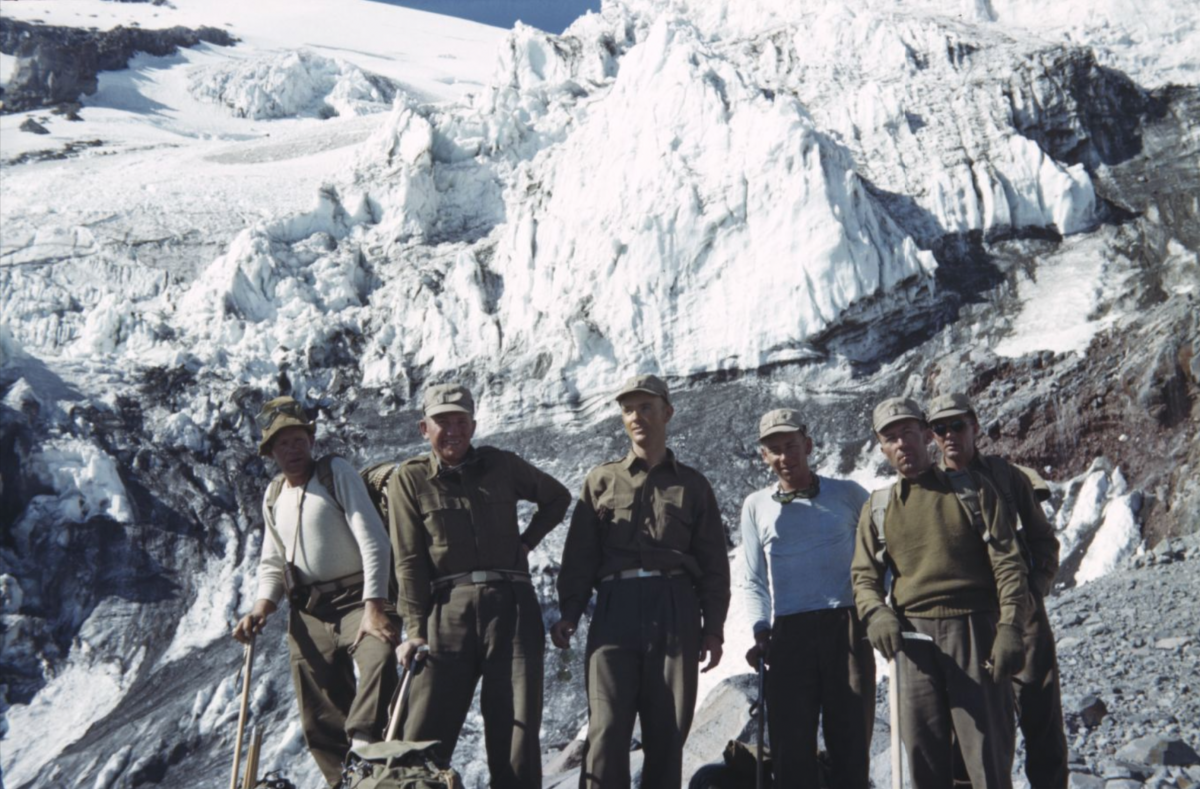

Photo above: Officers of the newly formed 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment on Mount Rainier in the spring of 1942. Forbidden by the U.S. Forest Service to fire live ammo, they trained troops in skiing and winter survival. Photo from 10th Mountain Division Resource Centery, Denver Public Library.

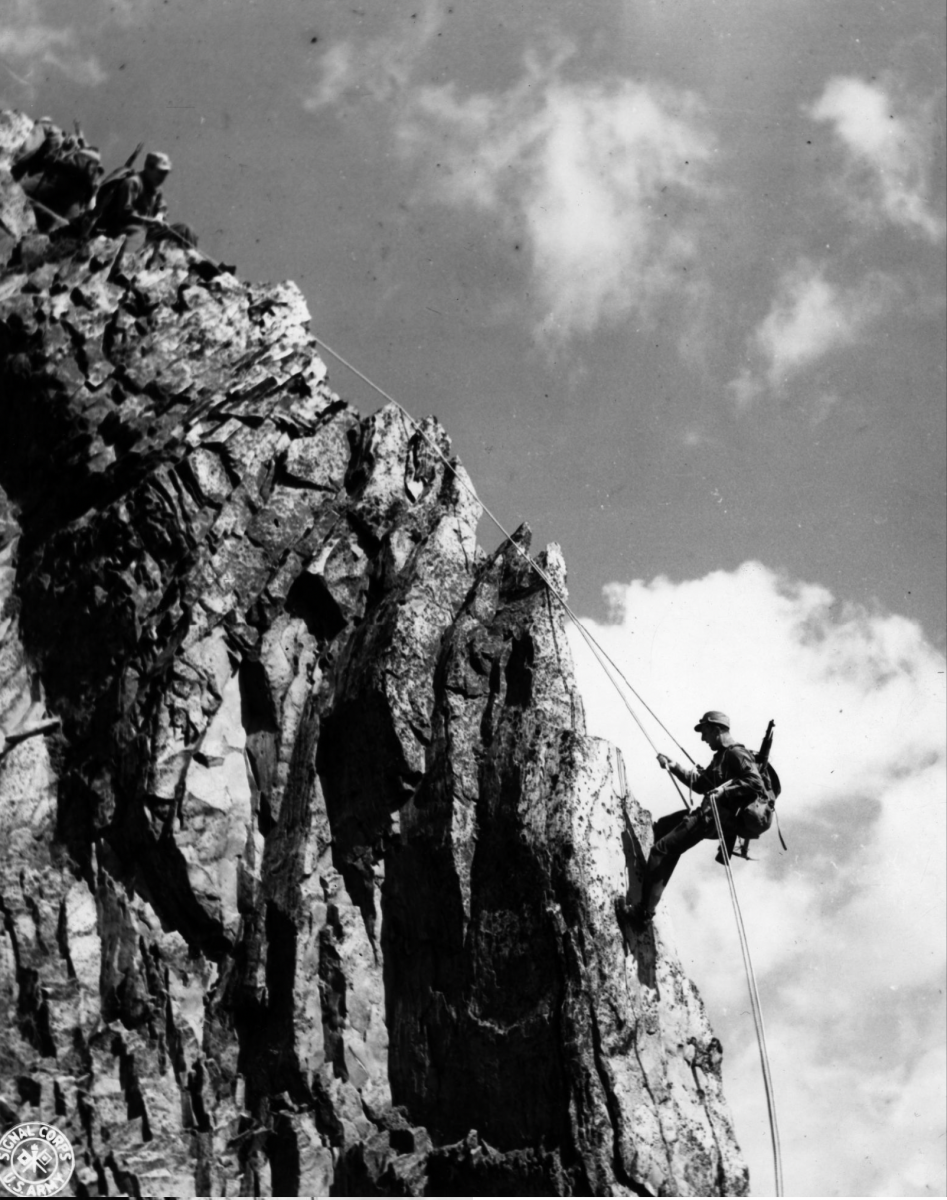

rappelling on Mt. Rainier for a

training films, 1942. Denver

Public Library.

Many in the army staff were skeptical, but as the Battle of Britain raged late that summer, Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall was convinced and ordered training exercises in the Adirondacks, the Upper Midwest, Wyoming and the Cascades. In November, Lt. John Woodward, a pre-war captain of the University of Washington ski team, was recruited to be an army skiing and mountaineering instructor. He was assigned to an existing unit, C Company of the 3rd Division, 15th Infantry Regiment at Fort Lewis, Washington, joining Captain Paul Lafferty, an experienced mountaineer.

Most men in the unit were from the Midwest and had no skiing or backwoods experience. But a second unit of 25 volunteers from the National Guard’s 41st Division at Camp Murray, adjacent to Fort Lewis, was composed of Northwest skiers. They trained at a Civilian Conservation Corps camp at Ashford, just outside Mount Rainier National Park, and commuted one day each week to Rainier for snow warfare instruction, based on methods used by Finland’s ski soldiers in the recent Winter War against the Soviet Union.

On December 12, Lafferty and Woodward took 18 volunteers to Mount Rainier, staying in quarters provided by the National Park Service. The men spent six weeks learning skiing and mountaineering skills, and combat tactics. They tested equipment and trained as ski instructors. By February 1941, there were 3,000 tents for temporary encampments at Fort Lewis and at Camp Murray, with 3,000 stoves that burned 200 cords of wood a day.

they needed long training days.

DPL.

That month, Lafferty and Woodward led the 15th on its final training maneuver, a seven-day trek from Snoqualmie Pass along the crest of the Cascade Mountains to Longmire in Mount Rainier National Park. Each man carried a rifle and a 40-pound pack with equipment and rations. The patrol attempted to avoid detection by an airplane that purposely checked on their movements.

Lafferty, who commanded the unit, reported the weather “warmed up and then froze, making an icy crust on the snow into which the skis of the men would not bite.” Due to prototype skis that were too stiff to float in snow, Lafferty developed shin splints while carrying a 65-pound pack and had to leave the trek. Woodward was put in charge. Navigation was difficult, and trail blazes were often buried. The men had topo maps, but it was easy to stray onto a spur ridge. They experienced hard spring snow and “had a heckuva time making the turns,” Woodward wrote. They hid from the airplane in forested terrain and were surprised when they were spotted. Because of the altitude, it took forever to boil food, so they ate powdered eggs and ham and other dehydrated food.

sleds. DPL.

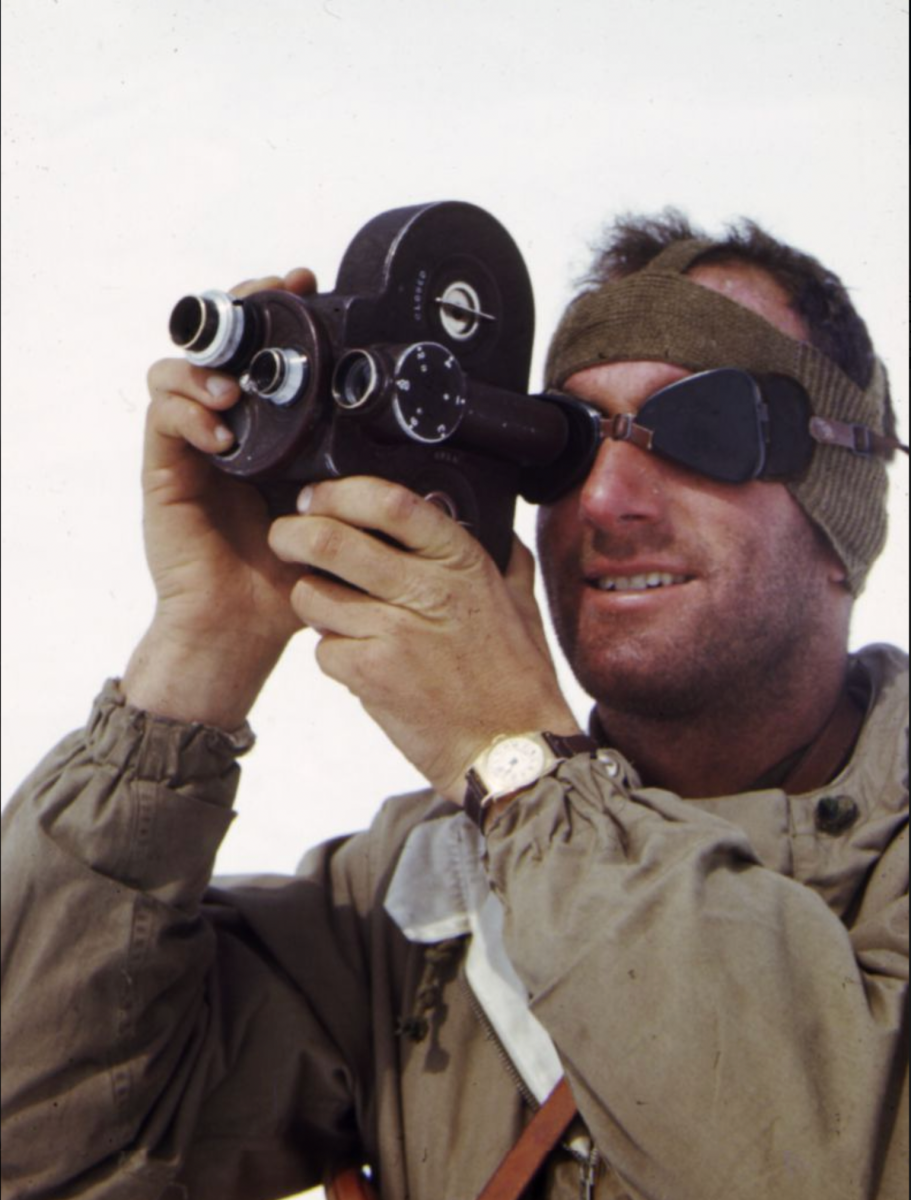

Later that spring, the first mountain-training movie made in America, The Basic Principles of Skiing, was filmed at Sun Valley by a crew from 20th Century Fox, with ski-teaching pioneer (and Hollywood director) Otto Lang as technical adviser. The cast featured a five-man detachment from For Lewis, led by Woodward and including Sgt. Walter Prager. An army photographer, John Jay, was assigned to the project. Sun Valley ski instructors stood in as soldiers. The film demonstrated that the Arlberg method of skiing was “well-suited to military skiing.”

The need for more mountain troops became a priority in 1941. In April 1941, German troops invaded Yugoslavia. On August 5, 1941, a memo for the army’s general staff reported on a battle in the Balkans where the Italian army was defeated due to the “lack of well-equipped mountain troops, organized, clothed, equipped, conditioned and trained for both winter and mountain fighting.” An estimated 25,000 Italian troops were killed and many captured, highlighting their inability to fight in mountains in winter conditions. The memo concluded, “such units cannot be improvised hurriedly from line divisions. They require long periods of hardening and experience for which there is no substitute.”

like this early snowmobiles. DPL

In April, Marshall ordered a search for a suitable high-elevation training camp (a year later, construction would begin at Camp Hale in Colorado). On October 22, he authorized the formation of the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment at Fort Lewis, consisting of the 1st Battalion, Companies A, B, and C. On November 15, just three weeks before Pearl Harbor, the army’s mountain troops officially began with the formation of a new experimental, oversized unit, the 1st Battalion, 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment (Reinforced). “Nothing like it had existed before in the entire history of the U.S. Military,” according to the official Army history of the 10tth Mountain Division.

Charles McLane, who skied at Dartmouth under Walter Prager, was one of the first to sign up for the 87th in fall 1941. In his book, Of Mules and Men, McLane wrote that when he showed up at Fort Lewis with an order to report to the mountain troops, the guards at the front gate thought he was kidding. Finally, a major read his orders, consulted headquarters and let him in, saying, “Lad, you are the Mountain Infantry. You’re a one-man regiment.”

Mt. Rainier, 1941. DPL

Top skiers from all over the country enlisted in the 87th. However, soldiers were not volunteering in sufficient numbers to expand the regiment into a full division. In late 1941, the National Ski Patrol (NSP) was made an official army recruiting agency and was asked to find 2,500 men with winter and mountain experience in 60 days, based on Charles Dole’s philosophy: “make soldiers out of skiers, don’t try to make skiers out of soldiers.” Ads were run in newspapers in areas around the country, seeking 18 to 20-yearolds who had lived in the mountains, such as rock climbers, trappers, guides and prospectors. If they could ski, so much the better. The NSP located 2,500 qualified men, within the deadline.

toward the summit of Mt. Rainier,

belayed againsta a crevasse

fall. DPL

Command of the 87th was assumed by Lt. Col. Onslow S. Rolfe, a calvary officer who didn’t ski. Woodward and Lafferty transferred into the 87th, assuming leadership roles because of their experience. Rolfe leased Paradise Lodge in Mount Rainier National Park for the 87th. In February 1942, the Seattle Times reported that 350 men moved into the lodge for winter maneuvers, with most non-skiers taking ski classes. Lafferty was in charge, directing 40 ski instructors.

That winter, troops resumed testing equipment and learning to ski while carrying up to 90 pounds. Forbidden by the National Park Service to use live ammunition, Woodward wrote, the 87th didn’t do much tactical training, but concentrated on ski technique, mountain orientation and trail breaking. The troops didn’t yet have enough gear for extended ski trips. The most important training was in winter survival and hygiene. During World War I, trench foot had knocked out a lot of troops in Europe. The men were taught to dry their socks in their sleeping bags at night, travel slower and take short breaks to keep from perspiring on the move.

Woodward and Lafferty had to decide whether the troops would use Swiss or Austrian ski techniques (see “10th Mountain Ski Technique,” Skiing Heritage, November 2017). Both liked the Swiss technique, which relied on stemming, unweighting and weight transfer to make turns. The Austrian Arlberg technique used an exaggerated upper-body rotation that led to overbalancing when wearing a heavy pack. Charles Bradley, a ski jumper from the Midwest, said in his book, Aleutian Echo,“they learned downhill techniques as fast as possible. ... [W]hen we were finally carrying rifles, a common misjudgment of speed and control could end with the load lifting the skier off the snow, rolling him forward in the air and driving him headfirst back into the snow. The rifle, lagging slightly, would now catch up and deliver the coup de grâce by whacking the skier on the head.”

on Mt. Rainier. DPL

While Walter Prager and Peter Gabriel championed the Swiss technique, the Austrian instructors would not comply, so the mountain troops were taught a “modified Arlberg,” using a stable wide track, stemming and foot-steering, with a quiet upper body to control the pack.

The 87th spent eight weeks on Mount Rainier. Ski instruction began on the first day on the mountain and continued for six hours a day, six days a week, in all weathers. At the end of the training period, 75 percent of the men qualified as military skiers, third class, on a course that civilian skiers would have had trouble handling, even without the packs and rifles.

glacier glasses against snow

glare. DPL

On March 29, 1942, the Seattle Times reported that when troops had arrived at Rainier, only 30 percent were experienced skiers, “but this 30 per cent included many of the nation’s best-known amateur and professional skiers. ... The 30 per cent instructed the remainder, and all now are adept on the long blades.”

In April 1942, a new training phase began on Mount Rainier, according to McLane. Heavy-weapons and service companies came to “try out skis and snowshoes, and toboggans.” Snowshoes ultimately proved better than skis for handling the heavy weapons and ammunition packs weighing up to 80 pounds. The troops “dropped ski instruction and pursued a simulated enemy in and out among the defilades of Paradise Valley carrying Garand rifles, Browning automatic rifles and light machine guns,” wrote McLane. They read books about Russian and Finnish warfare, and tried to adapt to their new medium. McLane continued, “But we stumbled, found ourselves clumsy and slow. We were not clever yet at fighting in the mountains. It would take time.” They learned how deceptive their white camouflage clothing was in snow, how effective wide flanking and hit-and-run tactics were and how to make use of higher elevations. “A good squad was not one that was tactically correct, but one that skied well,” McLane concluded.

during the test expedition, 1942.

DPL

Two kinds of mechanized equipment were tested. One was over-snow vehicles that were driven by a motor, with an airplane propeller mounted on ski-like runners. Woodward said they were narrow enough to fit in the bomb bay of a B-17 and worked well on roads or flat terrain, but were poor on hills since they tipped over easily. The other mechanized conveyance was tractor-like sleds with motorcycle engines (early snowmobiles), which did not work in Mount Rainier’s deep snow and on steep hills. Troops learned how to build igloos to hold four men, with vents to provide fresh air and a place for observation periscopes. The men wore reversible parkas, khaki on one side and white on the other. Rations were tested to cut down the bulk and increase the calorie content.

The army’s lease of the lodges on Mount Rainier ended in May 1942, and the 87th returned to Fort Lewis to train. Meanwhile, construction had begun on a new training facility at Camp Hale, Colorado, large enough to accommodate a division of 15,000 troops. According to Woodward, he selected 60 instructors as the Mountain Training Center Detachment, and they left Fort Lewis for Fort Carson, Colorado. After testing their instruction sequences in the mountains, they moved to Camp Hale in November 1942 and set up to welcome, and train, America’s future mountain troops.

ISHA Award–winning contributor John W. Lundin wrote about professionalism in early-20th-century skiing for the July-August issue of Skiing History.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Atomic USA

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Oppenheimer & Co. Inc.

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain Resort

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Kulkea

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snowbird Ski & Summer Resort

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Wendolyn Holland

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour