SKIING HISTORY

Editor Kathleen James

Art Director Edna Baker

Contributing Editor Greg Ditrinco

ISHA Website Editor Seth Masia

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Chan Morgan, Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Christin Cooper, Art Currier, Dick Cutler, Chris Diamond, Mike Hundert, David Ingemie, Rick Moulton, Wilbur Rice, Charles Sanders, Bob Soden (Canada)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Business & Events Manager

Kathe Dillmann

P.O. Box 1064

Manchester Center VT 05255

(802) 362-1667

kathe@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Commentary: Paradise Lost

Finally perfected after 30 years, the carving ski failed to gain a following in North America. In its place, we got a ski that has made resort slopes less safe.

(Photo above: Modern “shaped” skis were originally developed to help racers achieve the pure, carved turn—eliminating the braking effect of skidding. Ron LeMaster photo)

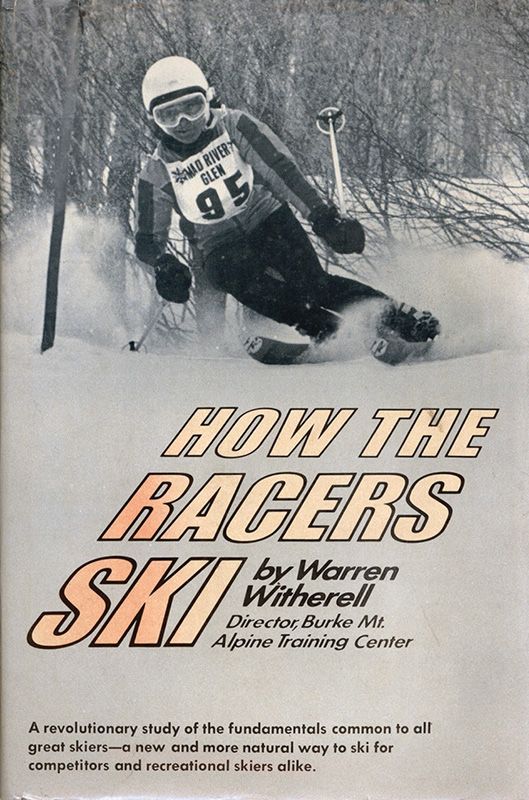

on traditional straight skis. This unidentified alpine

racer is approximating a carve, probably at a

World Cup race circa 1968.

For most of modern skiing’s history, the execution of a perfect turn has been an unobtainable ideal. Leather boots and wooden skis weren’t able to initiate and sustain a continuous, seamless carve. In the January 1967 issue of SKI magazine, Olympic gold medalist and Jackson Hole ski-school director Pepi Stiegler described a teaching method of getting the skis on edge so “the skis are literally carving the turn for you.” He called it the “Moment of Truth on Skis.”

“To start the turn, the skier should have the feeling of his weight going forward on the uphill ski and twisting the skis downhill. The resulting sensation is of a drift in the direction of the turn. At some split second during this process, the skier senses a moment to apply the edges and start the skis carving.”

At the time, the invention of plastic boots and the use of metal and fiberglass in ski design had brought the grail of the carved turn within reach. Stiegler, who became the NASTAR national pacesetter, clearly saw the desirability of recreational skiers knowing how to carve a turn.

The year before he died, the incomparable Stein Eriksen sent ski historian John Fry a package that included several photos of Stein in his iconic reverse-shoulder stance, along with a letter in which Eriksen asked Fry whether he should be considered the inventor of the carvedturn. Ever the diplomat, Fry replied that he doubted an uninterrupted carve was possible on 1950s-era equipment, “but if anyone could do it, it would be you.”

the idea of the carved turn as a goal

for young racers.

Perhaps the best-known apostle of the carved turn was Burke Mountain Academy founder Warren Witherell, who explained in How the Racers Ski (1972) what constituted a perfect carve: “In the very best racing turns, the entire edge of the ski passes over the same spot in the snow. The tip initiates the turn, biting into the snow and setting a track or groove through which the remainder of the ski edge flows.”

While Witherell’s gospel found faithful adherents in the race community, it failed to ignite interest among recreational skiers—in part because carving on a long,

pure carved turn on his Head

Masters (here at Sugarbush).

Fred Lindholm photo.

narrow ski was still a difficult skill to develop. While Witherell was preaching to the coaching choir, the public’s attention turned to the counter-culture phenomenon known as hotdog skiing, a.k.a. freestyle. Short skis would soon be all the rage, both as a means of abbreviating the learning curve and as a superior tool for moguls, aerials and ballet.

The concept of carving recaptured a toehold in the public’s consciousness with the advent of snowboarding and images of a steeply angled board sending up geysers of powder. The popularity of snowboarding and its short learning curve challenged ski designers to reconsider their assumptions about ski dimensions.

By 1995 there were just enough wasp-waisted models to muster a carving-ski category worthy of examination by Snow Country, where I oversaw the magazine’s testing. Over the next two seasons, deep-sidecut carving skis would render the relatively shapeless skis that preceded them obsolete. The universal acceptance of shaped skis appeared to augur a new world in which everyone would henceforth carve turns because every ski was a carving ski. The nirvana envisioned by Stiegler in the 1960s had been attained. (For the history of shaped skis, visit https://skiinghistory.org/history/evolution-ski-shape.) But...it didn’t happen.

Magic, 1998

The disruptive force that altered the path of ski design began innocently enough. When Atomic introduced the Powder Magic in 1988, its target audience was the heli-skiing patron who no longer would tire quickly in the bottomless snow, thanks to the new fat skis.

All the ski designer had to do to make the fat ski easier to steer was lift the tip and tail out of the snow, leaving a short foundation underfoot that could be swiveled side to side much more easily than it could be tilted on edge. The ski forebody, instead of seeking connection with the snow, now performed the same function as a Walmart greeter: It’s friendly but otherwise plays no part in what goes on behind it.

1991

If Warren Witherell was the evangel of carving, the Pied Piper of the emerging fat ski was Shane McConkey. McConkey wanted a better tool for attacking bottomless snow in extreme terrain. He persuaded his sponsor, Volant, to create the Spatula. The Spatula was the embodiment of the anti-carver, with a reverse sidecut and reverse camber. It inspired an explosion in the wide, rockered, all-terrain ski designs that currently dominate the U.S. market.

In the European Alpine countries where skiing has always had a broader base of participation, the notion that carving was a teachable skill found fertile soil. To this day, carving perfect turns on prepared slopes is central to the European ski experience.

Carving never caught on in America. A carved turn is best practiced on groomed terrain. Americans were more attracted to the versatility afforded by an all-mountain ski. By definition, “all-terrain” includes powder, and proficiency in deep snow depends on width. The appeal of skiing the entire mountain, and being properly equipped for the rare powder day, outweighed the allure of making a perfect turn every day.

surface of deep powder, permitting a pivot-and-slip

technique. It’s the opposite of carving.

Americans were enticed away from carving skis by fat skis that enabled skiers to easily swivel their way downhill. Lower-skill skiers can access ungroomed terrain they didn’t have the confidence to try before. But on regular groomed terrain at high speed, fat skis with limited edge contact don’t make for better or safer skiers. Quite the opposite. I’ll bet there aren’t ten people reading this who either haven’t been involved in a skiing collision, had a close call or knows someone who has been hit. The bottom line: Skis with waists from 75-90 millimeters would better serve the vast majority of skiers rather than models that are 100 millimeters and above. The wide platform of fatter skis does provide stability, but the trade-off in loss of quickness and edge control is not worth the price.

In a recent member survey, seniorsskiing.com found out-of-control, fast and reckless skiers and snowboarders to be the number-one grievance about the resort experience. “A few jerks skiing dangerously” and “risk-takers who don’t turn on groomers” far surpassed complaints about lift ticket prices, cafeteria food quality, and long walks to and from parking lots.

Carving skis offered a means of enabling skiers to control their speed and trajectory. The proliferation of highly specialized powder skis being used as everyday skis has had exactly the opposite effect. Not only are these skiers personally at risk, but everyone who shares our crowded slopes with them is also potentially in harm’s way.

Jackson Hogen is the editor of Realskiers.com, which tests and evaluates ski equipment. He is past General Secretary of the ASTM Committee on Ski Safety, and past Chairman of SIA’s Skiing Safety Committee.

.png)

Table of Contents

2020 Corporate Sponsors

World Championship

($3,000 and up)

Alyeska Resort

Gorsuch

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Obermeyer

Polartec

Warren and Laurie Miller

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

World Cup ($1,000)

Active Interest Media | SKI & Skiing

Aspen Skiing Company

BEWI Productions

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Country Ski & Sport

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Descente North America

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Fera International

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association (NSAA)

Outdoor Retailer

POWDR Adventure Lifestyle Corp.

Rossignol

Ski Area Management

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply, Inc.

Gold ($700)

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

Silver ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Clic Goggles

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Hertel Ski Wax

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

NILS, Inc.

Portland Woolen Mills

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snow Time, Inc.

Sports Specialists, LTD

SympaTex

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge & Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Vuarnet

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

For information, contact: Peter Kirkpatrick | 541.944.3095 | peterk10950@gmail.com

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!