SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Wendolyn Holland, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Einar Sunde, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Pro vs. Am: Class Warfare in Early American Ski Competition

Patrician attitudes initially dominated 20th-century sports.

In the late 1800s, professional sports attracted high-stakes gambling. The potential for bribery and extortion led to a general sense that paid athletes were corruptible and competitions untrustworthy. While betting on amateur events was common, a deep divide emerged between “pure” amateurs, who were said to compete for the love of the sport, and professionals, who competed for money in the form of cash prizes or other remuneration. The distinction often boiled down to so-called gentleman-athletes, who had private fortunes, versus working-class athletes, who had to earn money to live and train. Sport governing bodies consisted almost exclusively of gentlemen, who often preferred not to compete with working people.

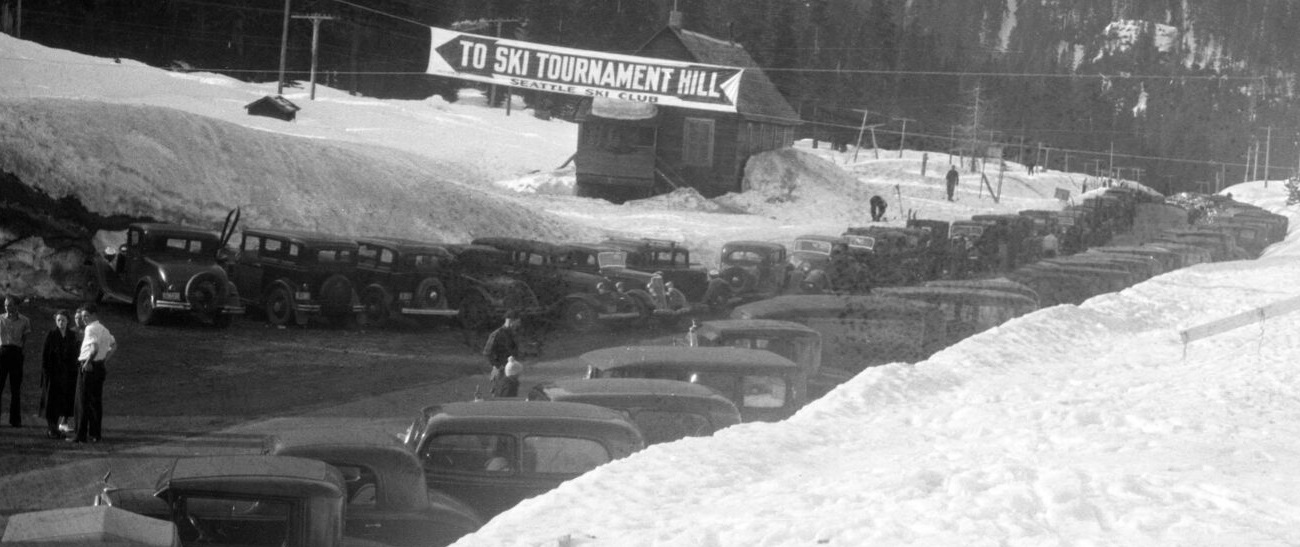

Photo, top of page: Ski jumping became a spectator sport, drawing huge crowds. Ski clubs sold tickets, and athletes wanted appearance money. Thus was born, in 1929, a professional ski jumping circuit. Photo courtesy Washington State Dept of Transportation.

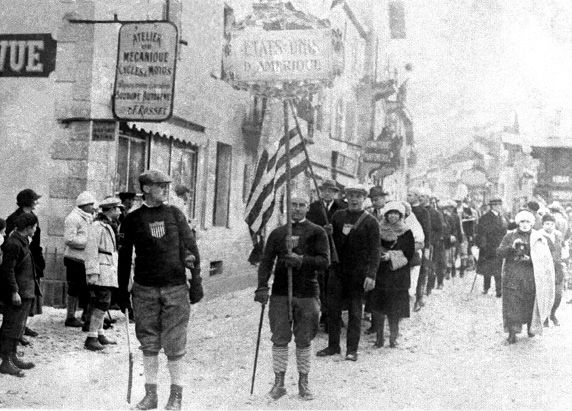

the first Winter Olympics in

Chamonix, 1924,

When Baron Pierre de Coubertin revived the ancient institution of Olympic competition in the 1894 Paris Congress, two governing subcommittees were created: the Olympic committee and the Amateurism committee. The word amateur was defined very loosely; nonetheless, de Coubertin gave it a strong ideological tie to the Olympics that proved very difficult to strip away.

Any participant who accepted financial benefit for any performance was considered professional, and the International Olympic Committee (IOC) acted quickly to disqualify athletes found to have done so. Olympic sport thus claimed to be untainted by the culture of cheating and scandal that was presumed endemic to professionalism. Avery Brundage, the IOC president from 1952–1972 and a staunch supporter of amateurism, said in 1955: “We can only rely on the support of those who believe in the principles of fair play and sportsmanship embodied in the amateur code in our efforts to prevent the games from being used by individuals, organizations or nations for ulterior motives.” This amounted to pure hypocrisy: Brundage himself, when he was president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, was complicit in the Nazi use of Olympic sport for political purposes.

Participation in the first modern Olympics in Athens, in 1896, was limited to gentlemen and military officers (who were granted automatic “gentleman” status). Professionals and the working class were excluded. The tradition continued when the Winter Games began in 1924. It became a flash point because skiing originated as a working-class sport, pursued by hunters, farmers, herders and common warriors from prehistoric times.

Especially in North America, the strictures on working-class participation in sport couldn’t stand. But the rules still favored those wealthy enough not to have to make a living from sport. Amateur athletes could not teach or coach sports for money, receive remuneration for participating in sport nor use their victories and reputations to promote any product.

Conflicts over Amateurism in Skiing

Harold “Cork” Anson, in Jumping Through Time: A History of Ski Jumping in the United States and Southwest Canada, described how skiing developed in North America as Scandinavian immigrants brought ski jumping to Minnesota, Michigan and Wisconsin. It became the “thrill sport of winter,” he wrote. Jumps were built on hills with enough vertical to provide good landings. By the end of the 1890s, Michigan had more than 30 ski clubs centered around jumping.

A trend developed during this period that was inconsistent with the Norwegian principle of idraet, the philosophy that an individual develops strength and manliness through exercise. In theory, a person jumps because of the love of the sport, not for reward. But for ski clubs, jumping was a spectator sport. To draw paying crowds, some clubs worked to attract top athletes who could provide the longest, most thrilling jumps. Clubs gave cash prizes to winning jumpers (based on both distance and style points) and for the longest jumps (regardless of style). The size of jumping hills was increased to set new distance records, “compromising the grace and beauty of well controlled flight,” and clubs offered top jumpers local employment as a recruiting tool.

In 1905, the National Ski Association (NSA) was formed in Ishpeming, Michigan, to promote skiing, standardize competition rules and ski jump design, and to establish standards of amateurism. In 1906, on the principle that money corrupted idraet, NSA decided there should be no cash prizes in competitions. It took 10 years for those prizes to disappear, however. Some ski clubs paid the expenses of outstanding jumpers to participate in their tournaments. Professionals found they could demand, and receive, appearance money. Separate distance records were kept for amateur and professional ski jumpers.

In 1927, at the annual meeting of the NSA in Red Wing, Minnesota, 30 “leading riders of America gave the group an ultimatum,” according to the Seattle Times (February 4, 1927). Either they be allowed to receive cash awards or they would establish their own association. The paper reported that “Crockery, silver-ware, medals, cash and professionalism were more animated subjects of discussion ... than the outcome of the various championship events.”

led the professional skiing

movement, later had his amateur

standing restored, revoved and

restored again.

Thus, in 1929, a number of Norwegian ski jumpers broke away from NSA and formed the Western American Winter Sports Association. WAWSA organized a professional ski jumping tour to compete around the United States in tournaments and exhibitions. Its members used tournament prize money to pay for travel. The group included Alf Engen, his brother Sverre, Sigurd Ulland, Lars Haugen, Einar Friedbo and others. Some of the country’s best jumpers did not join the tour, including Roy Mikkelsen and George Kotlarek, to preserve their amateur status so they could compete at the Olympics.

In 1932, the Cle Elum Ski Club in Washington asked Engen about appearing in its tournament. Engen replied that if “satisfactory terms” could be made, he would attend the event. “I am a professional and have arranged to jump in several tournaments this winter which offer some very attractive monetary rewards but, should you, however, make an offer which will make it worth my while to come to your city, I shall be very glad to jump upon your hill.” It appears the right offer was not made, as Engen was not one of the contestants in 1932.

Engen set a new world professional distance record in 1931 by jumping 247 feet at Ecker Hill near Salt Lake City. Over the next several years he repeatedly raised his own record. Engen won five National Professional Ski Jumping Championships from 1931 through 1935 and set three world professional jumping records.

Open Tournaments Permitted Ski Instructors to Compete

As Alpine skiing grew in popularity in the 1930s, and ski schools hired paid instructors, new issues relating to amateurism arose. In Europe, the International Ski Federation (FIS) ruled that ski instructors were amateurs and eligible to compete in FIS races. This did not fly with the International Olympic Committee. Olympic Alpine events were scheduled for the first time at the 1936 Winter Games in Garmisch, but the Nazi-run German team had a problem: their men had been shut out of the medals at the FIS World Championships in 1935. The IOC responded to pressure from Germany and excluded from the Garmisch Alpine events all the Swiss and Austrian men, on the grounds that they had worked as ski instructors. This opened a path for German skiers to win medals at the Olympics, while the Swiss and Austrians dominated the FIS Alpine Championships, held concurrently in Innsbruck with no Germans present.

In the United States, NSA considered paid instructors to be “FIS amateurs” who could not compete in amateur tournaments. When Sun Valley opened in December 1936, Averell Harriman set out to make his new resort an international destination and the country’s center of ski racing. He sponsored ski tournaments that attracted the best skiers in the world, and publicist Steve Hannagan made sure newspapers provided extensive coverage of the events. In his autobiography, Dick Durrance said Harriman “was determined that Sun Valley would match anything Europe had to offer.”

Harriman hired some of the best ski racers from Europe to teach in the Sun Valley Ski School, although as ski instructors, they were not eligible to compete in amateur ski races in this country. Harriman decided to host “open” ski tournaments, welcoming both amateurs and professionals, so his ski instructors could show off their skills.

In spring 1937, Sun Valley hosted its first International Open tournament, which would become known later as the Harriman Cup tournament. “The ski instructors are generally considered superior to the average American amateur” and were not permitted to race against true amateurs, according to coverage in the Seattle Times. The Sun Valley International Open was “the No. 1 tournament of the year, because it numbered all the skiing greats in its entry list.” Two championships would be awarded, for open and amateur, and ski instructors were eligible only for the open title, while amateurs were eligible for both. Separate prizes were awarded to the winner of each category. Forty-four of the best European and American skiers entered: eight ski instructors who were eligible for the open championships and 36 amateurs in “the greatest field of foreign and resident skiers ever assembled in North America.”

Seattle’s Peter Garrett, one of the Northwest’s best racers, later lamented that amateur skiers had to compete with better-trained professionals, “who ski seven days out of the week and make skiing their living.” He called for a new system in which pure amateurs and pros would race in their own divisions.

status after doubling for Sonia

Henie in Sun Valley Serenade.

Skiers Faced Discipline Over Amateur Issue

for endorsing Groswold Skis.

Engen immigrated to the U.S. from Norway in 1929 and became a U.S. citizen in 1935. Hoping to represent the U.S. in the 1936 Winter Olympics, he applied to be reinstated as an amateur. NSA ruled that an athlete could regain amateur status by proving he (or she) had not taken a sport-related payment for a full year. Engen did so, then out-jumped the competition at the Olympic trials and was named to the Olympic Team. However, Brundage, then president of the U.S. Olympic Committee, threw Engen off the team because his picture had appeared on Wheaties boxes (the “breakfast of champions”), along with those of basketball star Bob Kessler, hockey player Mike Karakas and speed skater Kit Klein. This made him a professional athlete, according to Brundage.

In late 1941, NSA revoked amateur status for Dick Durrance, Gretchen Fraser and Engen (again). Durrance was head of the Alta Ski School; in addition, both he and Engen endorsed Groswold skis. The NSA said that endorsing skis was allowed but that “use of a title and a record” made Engen a professional. The ski association said that Engen might be reinstated for open competition if changes were made to the advertisement, but it depended on whether the title and his record were used with his permission.

skiers off Olympic teams for

various sponsorship sins.

Fraser had been paid to double for Sonja Henie in skiing sequences in the 1940 movie Thin Ice and in Sun Valley Serenade in 1941. NSA ruled that she “will be a professional, eligible only as a F.I.S. amateur.” To address this issue, Northwest delegates to the NSA meeting were instructed to propose that all U.S. tournaments be open events under FIS rules.

In December 1941, NSA cleared Durrance of violating its rules. A skier could continue to be an amateur even if certified as a ski teacher, so long as he did not teach for money. Open-class competitors could endorse ski equipment “so long as titles were not thereby exploited.” In February 1942, Fraser and Engen each had their amateur status reinstated. The ski association determined that Engen endorsed Groswold skis but had not authorized the use of his record in any advertisement.

Olympics for appearing on a

Wheaties box.

In 1936, both the winter and summer 1940 Olympics were awarded to Tokyo, Japan (to the surprise of many), making it the first non-Western city to win an Olympic bid. After the second Sino-Japanese War broke out in July 1937, doubts were raised about whether Japan should host the Olympics. Japan formally forfeited the Games on July 16, 1938, and the IOC awarded the Summer Games to Helsinki, Finland, which had been runner-up in the original selection process. St. Moritz, Switzerland, was named as the new host of the 1940 Winter Games.

St. Moritz’s willingness to host the Winter Olympics was threatened when a dispute arose over the eligibility of paid ski instructors to participate in the Games. While FIS insisted that instructors were amateurs, the IOC ruled that they were professionals and ineligible. As a result of this conflict, the IOC eliminated skiing as a regular event from the 1940 Olympics, making it an exhibition sport.

Switzerland refused to host the Games at St. Moritz unless skiing were changed back to a regular event. The IOC refused to do so, and the Winter Games were transferred to Garmisch-Partenkirchen, Germany, the host of the 1936 Olympics. Of course, both the 1940 and 1944 Games were eventually cancelled due to World War II.

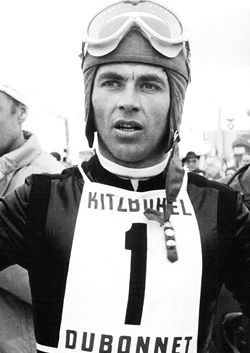

out of the 1972 Olympics.

After the war, the Winter Olympics resumed at St. Moritz in 1948, where Fraser competed as an amateur and won gold and silver, the first American to win an Olympic medal in Alpine skiing. Engen served as co-coach of the U.S. team with Walter Prager. Prager, a two-time World Alpine champion, Lauberhorn and Hahnenkamm victor and Swiss Nordic champion, was one of the Swiss ski instructors who had been barred from the 1936 Olympics. So he departed that year for America, to the benefit of Dartmouth College and the 10th Mountain Division.

As IOC chairman, Avery Brundage would campaign to exclude so-called professionals from “amateur” sports until his death in 1975. In his most notorious confrontation, he threw Karl Schranz out of the 1972 Olympics for signing endorsement contracts. In 1984, World Cup champions Ingemar Stenmark and Hanni Wenzel were banned from the Sarajevo Olympics for taking sponsorship money directly, rather than through their national teams. The IOC finally dropped the amateurs-only rule in 1986, permitting all athletes to deal openly with sponsors.

John Lundin has won four ISHA Skade Awards for books on the history of Pacific Northwest skiing and Sun Valley. He wrote about Sun Valley’s Ruud Mountain in the March-April 2022 issue of Skiing History.

Table of Contents

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000+)

BerkshireEast/Catamount Mountain Resorts

Gorsuch

Warren and Laurie Miller

Sport Obermeyer

Polartec

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corporation

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Atomic USA

Bogner of America

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar/Lange/Look

Gordini USA Inc/Kombi LTD

Head Wintersports

Intuition Sports

Mammoth Mountain

Marker/Völkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

North Carolina Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists Ltd

Sugar Mountain Resort

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD MEDAL ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sports

Race Place/Beast Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester NY)

Thule

SILVER MEDAL ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

EcoSign Mountain Resort Planners

Elan

Fera International

Holiday Valley Resort

Hotronic USA/Wintersteiger

Kulkea

Leki

Masterfit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Nils

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

SchoellerTextil

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Snowbird Ski & Summer Resort

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corp

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline Lodge and Ski Area

Trapp Family Lodge

Wendolyn Holland

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour