SKIING HISTORY

Editor Seth Masia

Managing Editor Greg Ditrinco

Consulting Editor Cindy Hirschfeld

Art Director Edna Baker

Editorial Board

Seth Masia, Chairman

John Allen, Andy Bigford, John Caldwell, Jeremy Davis, Kirby Gilbert, Paul Hooge, Jeff Leich, Ron LeMaster, Bob Soden, Ingrid Wicken

Founding Editors

Morten Lund, Glenn Parkinson

To preserve skiing history and to increase awareness of the sport’s heritage

ISHA Founder

Mason Beekley, 1927–2001

ISHA Board of Directors

Rick Moulton, Chairman

Seth Masia, President

Wini Jones, Vice President

Jeff Blumenfeld, Vice President

John McMurtry, Vice President

Bob Soden (Canada), Treasurer

Einar Sunde, Secretary

Richard Allen, Skip Beitzel, Michael Calderone, Dick Cutler, Ken Hugessen (Canada), David Ingemie, Joe Jay Jalbert, Henri Rivers, Charles Sanders, Christof Thöny (Austria), Ivan Wagner (Switzerland)

Presidential Circle

Christin Cooper, Billy Kidd, Jean-Claude Killy, Bode Miller, Doug Pfeiffer, Penny Pitou, Nancy Greene Raine

Executive Director

Janet White

janet@skiinghistory.org

Membership Services

Laurie Glover

(802) 375-1105

laurie@skiinghistory.org

Corporate Sponsorships

Peter Kirkpatrick

(541) 944-3095

peterk10950@gmail.com

Bimonthly journal and official publication of the International Skiing History Association (ISHA)

Partners: U.S. Ski and Snowboard Hall of Fame | Canadian Ski Museum and Hall of Fame

Alf Engen Ski Museum | North American Snowsports Journalists Association | Swiss Academic Ski Club

Skiing History (USPS No. 16-201, ISSN: 23293659) is published bimonthly by the International Skiing History Association, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255.

Periodicals postage paid at Manchester Center, VT and at additional mailing offices. Postmaster: Send address changes to ISHA, P.O. Box 1064, Manchester Center, VT 05255

ISHA is a 501(c)(3) public charity. EIN: 06-1347398

Written permission from the editor is required to reproduce, in any manner, the contents of Skiing History, either in full or in part.

Whatever Happened to Up-Unweighting

The keystone of skiing for decades, it’s largely been replaced by terrain-unweighting.

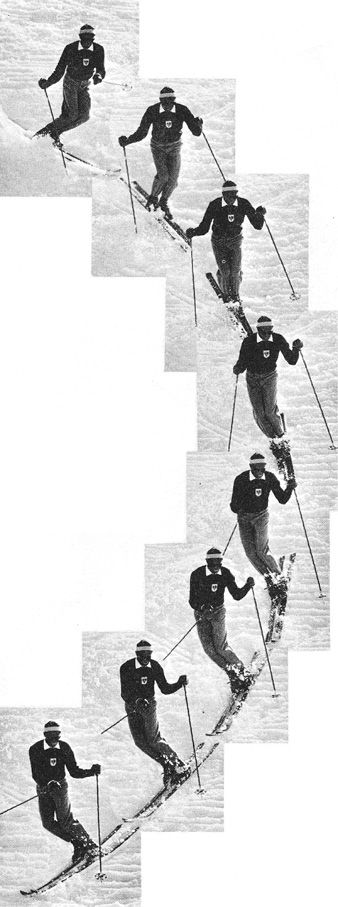

Photos above: Fred Iselin demonstrates “lift and swing” in a stem christiania. From Invitation to Skiing, F. Iselin and A. C. Spectorsky, 1947.

Exhortations of “down-UP!” used to ring from the lips of instructors and aspirational skiers as they initiated their parallel turns with up-unweighting. Countless one-page instructional tips in ski magazines reminded readers of its importance. Today, this former foundation of sound skiing is considered déclassé by many technically minded skiers. What happened?

eschewed rotation, but still espoused up-

unweighting. It was all in the knees and

ankles. From The New Official Austrian

Ski System, 1958.

The idea of “unweighting,” freeing the skis from the snow to facilitate starting a turn, goes back to the earliest days of Alpine skiing. And the obvious method of doing it was to toss the body upward. This was expressed well by Charles Proctor and Rockwell Stephens in their 1936 book, Skiing – Fundamentals, Equipment and Advanced Techniques. “[the] Christiania … starts with a rise or upward lift of the body, followed by a pronounced dip… The primary purpose of the rise and dip is to unweight the skis, for it is obviously easier to flick the heels out and thus start the turn when they are unweighted than when the runner’s weight is pressing them down into the snow.” In the days when slopes were ungroomed and the skis were long and stiff, “flicking the heels” demanded some significant unweighting. Brute force was needed, and the big “down-UP!” provided it. The technique was a cornerstone in ski instruction systems of all nationalities. Tyros were introduced to the first part of the movement pattern with “Bend zee knees!” The “UP!” came with the stem christiania, coupled to a strong upper-body rotation in the direction of the new turn.

Even as slopes became packed down and upper-body rotation disappeared from some teaching systems, making short, snappy turns with stiff wooden skis was more of an exercise in linked edge-sets than the linked arcs that became possible with the second generation of metal and fiberglass skis. Linking those edge-sets required significant “flicking of the heels” and pivoting of the skis, which in turn required significant and prolonged unweighting. Up-unweight was still the obvious choice.

Except in moguls. Once there were enough skiers on the slopes to create them, skiers figured out that they could employ the bumps to do the unweighting. Better skiers realized that oftentimes a bump could provide too much lift, turning each mogul crest into a ski jump. To avoid catastrophe, they learned to make the “down” but forgo the “UP!” entirely. Skiers’ bodies were still getting projected upward, but it was being done by the terrain, not the legs. Whether or not this is up-unweighting is an academic question, but the “down-UP!” was gone. (Some called this “down-unweighting,” but many technical aficionados argue that down unweighting is something quite different.)

flexes to absorb most of the unweighting

force as he links two short turns. Ron

LeMaster photo.

As skis and slope grooming steadily improved, the nature of short turns on all terrain has become more and more like skiing in moguls. The reason for this was revealed by Georges Joubert and Jean Vuarnet in their 1966 classic, How to Ski the New French Way (Comment se perfectionner à ski). At the beginning and end of a turn, the skis are traveling on a slope that is shallower than the fall line. So making a turn on a smooth slope is like skiing through a dip, and linking turns on that slope is like skiing through moguls. The sharper the turn and the steeper the slope, the bigger the “virtual bumps.”

A key aspect of improved ski design has also reduced the need for unweighting: The skis initiate turns more easily, and shape tighter arcs due to their shorter length and deeper sidecuts.

Through time, the details of the up-unweighting movement evolved. Before the Austrian school stormed the ski world with wedeln, short-swing and their innovative system of the late 1950s, skiers were taught to flex and extend at the ankles, knees, and waist. The new Austrian method encouraged skiers to do it all at the knees and ankles, thrusting the knees forward as they were bent, while remaining erect from the waist. This became the fashion, even though the best racers of the time bent much less at the ankles and more at the waist. In the mid 1960s, it became apparent that the best racers were skiing in more of a seated position: still bending their knees a lot, but bending more at the waist and less at the ankles. This presaged the advent of tall plastic boots in the 1970s that greatly limited the range of ankle flex but greatly improved the skier’s ability to work the skis. Since then, that way of moving up and down has remained with us.

uses a variety of unweighting techniques,

including up-unweighting, to achieve

different ends in each turn. Ron LeMaster

photo.

Today, snow grooming and ski design are so good that not only is less unweighting usually required than in the old days, but that which is needed is often provided by the dynamics of the turn itself. The skier simply goes along for the ride or, in more dynamic turns, flexes to absorb the excess unweighting that the turn would otherwise produce.

This is not to say that up-unweighting is gone from the repertoire of the good skier. Whether you define up-unweighting as leg-powered lift, or broaden the definition to include terrain-induced lift, it’s still with us. Even under the narrower meaning, it’s the sharpest tool in the skier’s kit for many situations. Used with a bouncing rhythm, it’s a go-to technique for introducing tyros to powder snow, and all experts often find themselves doing a big down-UP with a forceful upper body rotation in heavy, unpacked snow. In good skiing generally, unweighting by extending is often useful, effective and commonplace. Moreover, it gives your leg muscles a chance to relax, expands your chest so you can breathe deeper, gives you a better view of the slope below, and just plain feels good.

Table of Contents

Corporate Sponsors

ISHA deeply appreciates your generous support!

WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP ($3,000 AND UP)

Gorsuch

Polartec

Sport Obermeyer

Warren and Laurie Miller

CHAMPIONSHIP ($2,000)

Fairbank Group: Bromley, Cranmore, Jiminy Peak

Hickory & Tweed Ski Shop

Rossignol

Snowsports Merchandising Corp.

WORLD CUP ($1,000)

Aspen Skiing Company

Berkshire East Mountain Resort/Catamount Mountain Resort

Bogner

Boyne Resorts

Dale of Norway

Darn Tough Vermont

Dynastar | Lange | Look

Gordini USA Inc. | Kombi LTD

HEAD Wintersports

Intuition Sports, Inc.

Mammoth Mountain

Marker-Volkl USA

National Ski Areas Association

Outdoor Retailer

Ski Area Management

Ski Country Sports

Sports Specialists, Ltd.

Sun Valley Resort

Vintage Ski World

World Cup Supply

GOLD ($700)

Larson's Ski & Sport

Race Place | BEAST Tuning Tools

The Ski Company (Rochester, NY)

Thule

SILVER ($500)

Alta Ski Area

Boden Architecture PLLC

Dalbello Sports

Deer Valley

Ecosign Mountain Resort Planners

Fera International

Holiday Valley

Hotronic USA, Inc. | Wintersteiger

MasterFit Enterprises

McWhorter Driscoll, LLC

Metropolitan New York Ski Council

Mt. Bachelor

New Jersey Ski & Snowboard Council

Russell Mace Vacation Homes

Schoeller Textile USA

Scott Sports

Seirus Innovations

SeniorsSkiing.com

Ski Utah

Steamboat Ski & Resort Corporation

Sundance Mountain Resort

Swiss Academic Ski Club

Tecnica Group USA

Timberline

Trapp Family Lodge

Western Winter Sports Reps Association

World Pro Ski Tour

Yellowstone Club